“You would screw it up!” he said, and he started off, aiming upriver at forty-five degrees. The river was only two or three hundred feet wide, but the crossing proceeded slowly, because we were moving southwest and northwest at the same time. My heart was beating between my teeth. The left bank was almost uniformly high and steep there, but Len hit a spot where a gully had worn down. The next day, we crossed the river twice, just to go to Maupin and buy more flies. Thanks to his instructions and suggestions, I caught five rainbows, inspiring me to write:

When Len was eighty-eight, we started down the John Day. Roger Bachman was aboard, Len rowing us in his boat. Farther east, and like the Deschutes, the John Day is a north-flowing tributary of the Columbia River. Known for its bass, it doesn’t have the world-class reputation the Deschutes has for its steelhead and trout. Scarcely a mile from launch, we received an omen from John Day. Len ran up on a boulder in the middle of the river. Stuck fast, we rocked back and forth and side to side and Len scraped rock with the oars. We were there quite a while. Gradually, our commotion inched the boat off the boulder. And soon we heard a rumble of thunder, and sooner still another. We hadn’t gone five miles when we decided to make camp early. Lightning was all over the place and rain with it. Thunderstorms don’t last forever. Under a tarp, just sit and wait. And wait. And wait forever, it seemed. More rain. Who expects rain in June in eastern Oregon? The shade of John Day, evidently. All-night rain. Wearing waders, wading boots, waterproof jackets, we saw no point in taking anything off. Just lie on the ground with the tarp, in water streaming by. With daylight, we bailed out the boat, went on to the next bridge, and managed the recovery of the car. In a lifetime of sleeping some hundreds of nights on the ground, that for me was the last one. To date.

And now, two years later, we’re on the McKenzie River with the professional guide George Recker, and we have had our lunch: the ten-inch trout we were catching this morning. George prepared them, and grilled them naked. Skinless. After beheading each one, he pinched it with his thumbs and forefingers at the pectoral fins and flipped it over-end with a powerful snap. The body popped out of the skin, looking less like a fish than a frankfurter.

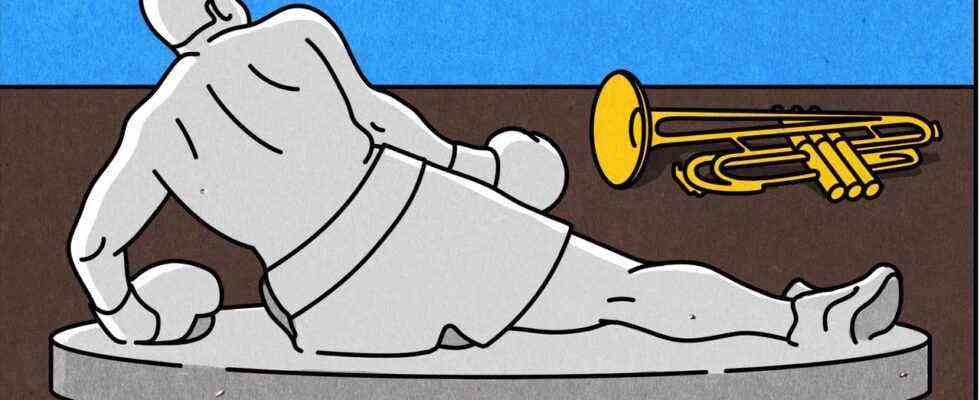

Back on the river, Recker, with little choice, followed Dr. Dick downstream. As we fell farther behind, George became concerned about his ninety-year-old client. In case of trouble, shouts would not be heard. And there soon arose a situation of real alarm. At the far end of a long right-bending curve, the river was really wild. We could make out in the distance its snapping white jaws. Dr. Dick was rowing blithely toward the jaws. George reached into his kit. He removed a miniature trumpet, stunningly beautiful, in silver and gold. Also employed as a professor of music at the University of Oregon, George Recker the professional fishing guide had been first trumpet for operas at the Kennedy Center, in Washington. He lifted the miniature trumpet to his lips and produced a long clear note that may have reached the moon. It sent Dr. Dick to the riverbank.

DINNERS WITH HENRY LUCE

Henry Luce, the co-founder of Time: The Weekly Newsmagazine, would try to get to know new writers by inviting them to dinner at his New York apartment. At least, he was doing that when I was a new writer, thirty-four years after the founding, when Luce was living for the most part in Arizona and was not a presence in the magazine’s offices. I went to two of those dinners, each time seated with some eleven other writers at a long table, as if Leonardo da Vinci were on hand, too. Luce asked questions, going around the table from face to face for answers. One such dinner, in the summer of 1960, occurred after Richard Nixon had won the Republican nomination for President and before he had made his choice of a candidate for Vice-President. Two of us—Jesse Birnbaum and I—sat side by side at one end of the table, Luce alone at the other end. He was sixty-two but looked and seemed older. In his voice was the scratch of antiquity. After several rounds of questions, my attention span collapsed, a general tendency in my psychological makeup that I am shy to acknowledge. There came a question that I failed to hear, and down the right side of the table five answers were given, all of which bypassed whatever daydream I was having. The substance of the question was who did the young writers think Nixon’s choice would be. Jesse Birnbaum was on my left, so I was number six in line. The fog lifted suddenly when, looking down the table, I saw five people on either side and Luce at the far end looking at me expectantly—at me, clueless and catatonic. Jesse Birnbaum saved me by almost inaudibly whispering, “Henry Cabot Lodge.”

“Henry Cabot Lodge!” I said, with conviction.

At the other dinner, Luce’s questions were more personal than political. He had gone around the table two or three times when he asked, in effect—I forget how he put it—What is your religion? Luce had credentials in religion. His father was a Presbyterian missionary in China, where Luce was born, in 1898. He had attended the China Inland Mission School, in Chefoo, and now he looked down the table for answers to his question. A variety of faiths were mentioned one after another, until all eyes turned to John Alexander Skow. Known to most of us as Jack, he was never unforthcoming. His tone was always gentle, and he was afraid of nothing. In answer to Luce’s question, he said, “Atheist anticlerical.”

“Wha- wha- wha- what did you say?” said Luce.

“Atheist anticlerical.”

Luce became a captive. From that point forward, the evening was composed of nothing but Luce and Skow. While the two of them wrapped each other in rhetoric, the rest of us might as well have crept away.

CITRUS, BOOZE, AND AH BING

After I wrote a book called “Oranges,” which was about oranges, it caused enduring wonderment in the book press, the inference being that the author of anything like that must be substantially weird. “He wrote a whole book about oranges” has been the most repeated line, with the word “whole” all but printed in orange italics. “He wrote a whole book about oranges, his favorite fruit” is an analytical variation, though contrary to fact. My favorite fruit is the Bing cherry. And my favorite whiskey is not spelled “whisky” and happens not to be single-malt Scotch, the subject of a study that I wrote called “Josie’s Well,” which is part of a collection called “Pieces of the Frame.” I didn’t need all the diagnostic wonderment to become sane enough not to write about Bing cherries or bourbon. Who wants to be typecast?

In 1965, when I was new at The New Yorker, I asked William Shawn, the magazine’s editor, if he thought oranges would be a good subject for a piece of nonfiction writing. Fifty years later, in the New Yorker issue of September 14, 2015, I described what had happened next:

The idea for “Josie’s Well” as subject and title of a piece on single-malt whisky developed in a bathtub in the Hebrides. Living on a croft, our family was there for some months in early 1967. Our older daughters enrolled in the island school, while I interviewed people and gathered experience on the ancestral island in preparation for a long piece of writing. The whisky was incidental, a variety of single malts—Talisker, Laphroaig, Glenlivet, Macallan—in sipping jiggers at the side of the tub after long days hiking in sequences of sunshine and cold misty rain.

Proofs aside, why the strong taste of island whiskies? Why the mild elegance of the whiskies of Speyside? Why did Laphroaig suggest thick-sliced bacon? In Speyside, on Isla, on Skye, I later interviewed the distillers, including Captain Smith Grant, whose artesian spring, called Josie’s Well, was out in the middle of a field of oats near Ballindalloch, Banffshire, and was providing thirty-five hundred gallons an hour to the stills of The Glenlivet.

I prefer bourbon. Admitting it is painful. Disloyalty to ancestors often is. But facts are facts. Single-malt Scotches are for birthdays. Bourbon is for the barricades. The closest I ever came to forsaking my principles—the literary creed that one kind of whiskey is enough for one writing lifetime—came in 2004, when I was working on an unrelated story in Kentucky and had a weekend to kill on my own. I just drove aimlessly around the center of the state. Well, not altogether aimlessly. As a quotidian sipper of bourbon, I gravitated to distilleries, just to see their settings and what they looked like, the possibility of a piece on bourbon now not so far back in my mind. In a park in Bardstown, Kentucky, Stephen Foster’s “My Old Kentucky Home” in continual performance poured down from loudspeakers in the crowns of trees. That cooled the story project right off the bat, the fact notwithstanding that Heaven Hill, of Bardstown, Kentucky, was making Elijah Craig and Fighting Cock. Barton, of Bardstown, was making Tom Moore. Driving on, this is what I also learned: Jim Beam, of Clermont, Kentucky, made Knob Creek, Old Grand-Dad, Booker’s, Baker’s, Basil Hayden, and I. W. Harper. Brown-Forman, of Louisville, Kentucky, made Early Times, Old Forester, and Woodford Reserve. Buffalo Trace, of Frankfort, Kentucky, made many other not-well-known brands, including Pappy Van Winkle. Bernheim Distillery, of Louisville, Kentucky, made Rebel Yell. Maker’s Mark, of Loretto, Kentucky, made Maker’s Mark.

I have been through most of that list—not smashed before a row of jiggers but sober, scientific, and sensitive to the lighter, rather objectionable alcohols (a phrase I picked up from George Harbinson, when he was the managing director and chairman of Macallan, in Speyside). A bourbon previously unknown to me was Bulleit, whose label said it was from Louisville and did not mention age. Its Web site said it was from Lawrenceburg, Kentucky, and was five to eight years old. Lawrenceburg, Kentucky, on the deeply incised Kentucky River, is where Austin Nichols makes Wild Turkey. The view from far above, down at the distillery across the river, is competitive with scenes along the Rhine. Driving around Kentucky looking at distilleries is a good way of getting to know the state, and it beats the hell out of horses.

My closest call ever with the Bing cherry came in 1982, during a touristy drive through northwestern Washington on a route that crossed the Cascade Range and went down into the Okanogan Valley. Trending north through Washington and into British Columbia, the Okanogan Valley is the Oxford and Cambridge of the Bing cherry. Aware of this and caving by the minute, I had learned the name of a widely admired orchard we would pass, owned and farmed by a knowledgeable married couple who will prefer to remain nameless.

This cherry had been bred in 1875 at an orchard in Oregon, on the Willamette River, just south of Portland. In an open-pollination cross, its mother was a Black Republican and its father a Royal Ann (sic). The orchard foreman was Ah Bing. A Manchurian well over six feet tall, he spent several decades in the United States, sending home to his wife and children money from his long employment at what had been one of Oregon’s pioneer nurseries. Its founder, Henderson Lewelling, brought his fruit trees and his family overland by oxcart from Iowa.

In a memoir written many years after the fact, a member of the Lewelling family recalled that Ah Bing had under his personal supervision the row of test trees in which the successful cultivar appeared. In any case, he was the foreman and the cherry was named for him. Taxonomy went elsewhere. The Bing cherry, of the species Prunus avium, has the medicinal implications of a prune. Ripening, it tends to split if too much rain falls on it. Hence this red cherry, by far the most popular in America, is mainly grown in the dry-summer valleys of Washington, Oregon, and California.