1.

The path to Walden, as you walk north along the western edge of Adams Woods, comes to a fork just beyond the Concord line. If you’re heading to Henry Thoreau’s most famous pond, take the trail to the right for a half mile or so, keeping the swampy Andromeda meadows below you on the left, until you cross the tracks of the Fitchburg railroad and you’re standing on the shore looking north across the water toward Henry’s cove, his cabin site hidden in the dense woods on the higher ground.

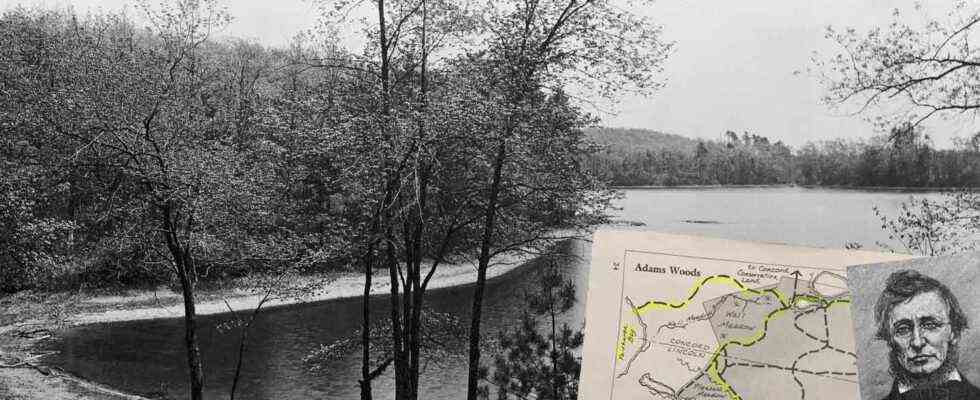

For the past 10 years, however, ever since I discovered this route, I’ve taken the left fork more often than not, winding down to Fairhaven Bay on the Sudbury River, a hidden lake, really, more or less the size of Walden, with steep, thickly wooded embankments. Many people, even locals, don’t know it exists; it’s accessible only if you know the trails, or paddle down the river, or happen to own one of the large properties that surround it. It’s one of the most secluded and one of the quietest spots in the area, with Walden’s crowds a mile away, and still among the best for seeing the local waterfowl.

I’ve walked this way to Fairhaven several times a year, at least once in each season, since Henry’s Journal led me to it a decade ago. But I confess that in more recent years my visits have become rarer. I suppose you could say, as Henry once did, that the remembrance of my country spoiled my walks.

So it felt good on a morning last fall to get my head out of my various screens and their endless election “takes,” and to set out on the trail from Lindentree Farm in Lincoln up through the woods to Fairhaven. The morning was clear and cool, the first maples already showing off their reds. It was only as I got out of the shadows and into the broad clearings of the farm that I noticed the high atmospheric haze discoloring the sun in an otherwise cloudless sky—smoke carried thousands of miles on the jet stream from the raging, terrorizing wildfires on the other edge of the continent—and realized that the sunlight on the ground at my feet and on the stalks and leaves of the crops was slightly dimmed, as though faintly tinted.

Nevertheless, or maybe for that very reason, when I entered the woods at the far side of the farm fields, the details of the forest floor and understory leaped out at me. My senses jolted awake in a way they hadn’t been for quite some time. Every leaf and mossed log, every shadow and every sunlit patch of undergrowth became distinct and vivid, as if I’d never seen such a sight before. When I got to Fairhaven I sat on the stone landing by the old boathouse on the north shore. The water was low. Mud stretched several yards in front of me, dotted with lily pads, and the water’s surface was swept by a steady breeze coming from the southwest. A few ducks paddled along, and off to my left about a hundred yards away a great blue heron stood statuesque at the water’s edge, the subtly altered sunlight glinting on the wavelets.

Still precious: Fairhaven Bay as it appears today—over a century and a half after Thoreau. (Wen Stephenson)

It struck me that day in September how little the forest and the pond had changed in the 10 years since I discovered that spot at Fairhaven. Back then, as I was first really awakening to our planetary crisis, I wondered how much longer we would recognize Henry’s woods. In spite of New England’s rising temperatures—our later, warmer autumns, shorter winters, earlier springs—the changes, thus far, have been too subtle for my untrained eyes. But we know far greater change is coming, and soon.

These woods around Fairhaven were Thoreau’s playground, laboratory, sanctuary. “In all my rambles I have seen no landscape which can make me forget Fair Haven,” Henry wrote in his Journal at the end of May 1850. “The sight of these budding woods intoxicates me.” But they were never a remote or pristine wilderness in his day—indeed they were less so than in ours. They were part and parcel of the surrounding social world. This landscape was far less forested in Henry’s time, cleared for farms and grazing land, and the woods were mainly kept for fuel and lumber. Henry saw the landscape change from decade to decade, even year to year. He saw the railroad come through, skirting Walden’s western end. And he described in 1851, less than four years after his experiment at the pond, how the woods where he’d lived had been cleared for a farmer’s field and all the evidence that remained of his cabin was the impression of the cellar hole.

Henry was fascinated by the constant cycles of change and regeneration, transience and resilience, whether the timescale was geological or seasonal, or that of human generations. He felt the natural history of the ground he walked. He had deep respect for the Indigenous peoples of Massachusetts and New England, whose lands the Europeans had taken, and he may well have known more about them than any of his contemporaries, researching, conducting interviews, collecting artifacts as he amassed the several volumes of his pathbreaking “Indian Notebooks.” For Henry, the past and present, human and wild, coexisted in the eternal flux of the here and now.

He had even been the cause of a sudden, violent change in the local landscape. As a young man, in the unusually dry spring of 1844, he and his friend Edward Hoar cooked up a mess of fish on the northeastern edge of Fairhaven Bay and accidentally set fire to these very woods. Henry ran to alert the landowners while Edward raised the alarm in Concord, but a hundred acres burned, all the way to the cliffs of Fair Haven Hill, before the townspeople contained it.

Looking back on the experience years later, Henry admitted having felt some guilt, but he quickly got over it, dismissing the complaints of the woods’ “owners, so called.” He remembered thinking to himself, “I have set fire to the forest, but I have done no wrong therein, and now it is as if the lightning had done it.” Indeed, the budding ecologist in him saw the “advantage” of the fire to the local ecosystem, as the Native Americans well knew. “When the lightning burns the forest its Director makes no apology to man, and I was but His agent,” he wrote in his Journal. “It is inspiriting to walk amid the fresh green sprouts of grass and shrubbery pushing upward through the charred surface with more vigorous growth.”

“That night I watched the fire,” he recalled, “where some stumps still flamed at midnight in the midst of the blackened waste.”

Henry’s scorched earth was the very ground I now walked to Fairhaven.

2.

It wasn’t the rosy-fingered dawn rising out of the Aegean, but one early-October morning I saw the sun thrust through the range of clouds on the Atlantic horizon from the high bluff at the Nauset Light, not far from where Henry Thoreau first glimpsed the eastern shore of Cape Cod. What compels a man in his 50s to get out of bed three hours before sunrise and drive to the Cape, just so he can see what a long-dead writer saw and walk where he walked? Though not precisely where he walked—Henry’s path along the beach on what is now called the National Seashore has long since gone under the waves.

If you’ve never viewed it, that eastern edge of Cape Cod from Eastham to Race Point is one wide and all-but-untouched strip of beach, curving from due north to northwest and west, rimmed by massive sand bluffs that rise at times a hundred feet or more above the waterline and then become a broad expanse of dunes at the Cape’s northern end. For long stretches of the beach, no houses or any other human structures are visible—only sand, bluffs, and ocean as far as the eye can see.

Henry walked the entire 30-some-odd miles, first with his friend Ellery Channing in October 1849, then by himself the following summer. I didn’t have that kind of time on my hands, so I picked a long, empty section that Henry described in his book Cape Cod, north from Newcomb Hollow near the Wellfleet-Truro line.

The temperature that morning was in the low 40s, and a battering wind blew out of the north, numbing my cheeks, piercing the fleece I wore. The sky was so clear it was almost dizzying, the ocean a rich, dazzling turquoise and blue, white-capped to the horizon, the breakers rolling in slantwise to the coast, their salt spray in my face. I walked north for about three miles and back again, alternating from the firmer wet sand to the fine, dry, clean-swept expanse above the tidemark—more than two hours without seeing another human. I was utterly alone except for the seabirds and a few curious seals keeping pace with me close to shore, popping their heads out of the water like friendly dogs. But there on the dry sand it was only me. Turning around, I could no longer see where I’d started, my footprints vanishing into the distant glare, and in front of me an infinite vista of sand, sea, and sky. I imagined myself seen from high above, a solitary figure trudging into the hard, relentless wind, as sand blew in sheets across the ground in front of me and over my boots. The bluffs loomed above me, as high and as steep and as rugged as a canyon wall—like some desert landscape in my native Southwest.

We’ve so domesticated “the beach,” nowhere more so than on Cape Cod, that we forget it actually is a kind of desert, just as Henry said. I was walking across a desolate no-man’s-land, a death strip for all but the most minutely adapted life-forms—a boneyard for the rest of us.

“They commonly celebrate those beaches only which have a hotel on them,” Henry writes in Cape Cod. “But I wished to see that seashore where man’s works are wrecks.” Death is much on his mind in that book, and he tells of how he was once tasked with finding the shark-eaten remains of a human body cast up on the beach a week after a shipwreck. “Close at hand,” he writes, these “relics…were simply some bones with a little flesh adhering to them…. There was nothing at all remarkable about them…. But as I stood there they grew more and more imposing. They were alone with the beach and the sea, whose hollow roar seemed addressed to them.”

Alone with the beach and sea, I didn’t find any bones, human or otherwise, or any evidence of a shipwreck. But I did come across an occasional beached and half-buried lobster trap, broken loose from its mooring. One of them struck me as an art installation, situated on that barren beach as though in a surreal, post-apocalyptic gallery. But then I thought about the living human hands that made it and made their living by it. And I thought about the creatures it trapped, and about the warming, acidifying water.

The bluffs have retreated dramatically since Henry’s time, thanks to storms and the inexorably rising sea, now at least a full foot higher. In places, the erosion has exposed the rock and clay midway up the bluffs, as in a canyon wall, and you can see the strata measuring geological time. Elsewhere, a few limbs and roots of trees protrude from the sand on the steep slopes, evidence of the erosion’s inland progress.

How far will the water come? If the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets collapse entirely—and science tells us they will if business as usual continues—then the global sea level will ultimately rise more than 200 feet. The highest of these bluffs will be submerged, as will most of the East Coast. Even in the best-case climate scenarios, requiring revolutionary changes in our politics and economy, we can expect a meter or two of sea-level rise by later this century, possibly within my lifetime. The beach I walked will be a seabed. Henry’s beach, somewhere out there where the seals and sharks swim, already is.

“The sea-shore is a sort of neutral ground, a most advantageous point from which to contemplate this world,” Henry writes. “Creeping along the endless beach amid the sun-squawl and foam, it occurs to us that we, too, are the product of sea-slime.” There on the shore, much as he did on Maine’s Mount Katahdin, Henry encountered an inhospitable, inhuman nature:

It is a wild, rank place, and there is no flattery in it…a vast morgue…. The carcasses of men and beasts together lie stately up upon its shelf, rotting and bleaching in naked Nature—inhumanly sincere, wasting no thought on man, nibbling at the cliffy shore where gulls wheel amid the spray.

Standing there at the edge of a continent, a clear horizon revealing the curve of the Earth, it occurs to me that we do in fact live on a planet—I, and countless other humans, whose fate means nothing to sand, seawater, or seal. The waves will come, the shore will shift, with or without us, just as it did long before us and always will, long after us.

The so-called Anthropocene matters only to those who conceive of it. To those who suffer it, whether they conceive of it or not, it is only a matter of survival.

3.

In the predawn hours of Sunday Morning, December 8, 2019, I stood with a dozen others in the snow on the freight tracks in Ayer, Mass., in front of a train carrying 10,000 tons of West Virginia coal. The train was bound for the power station in Bow, N.H., the last big coal-burning plant in New England. That same train had been blockaded a few hours earlier coming out of Worcester to the south, and it would be blockaded again on the truss bridge across the Merrimack River in Hooksett to the north. Two more coal trains would be blockaded in the weeks ahead. More than a hundred of us were arrested, all part of a grassroots campaign to shut down that coal plant and, ultimately, bring an end to the burning of fossil fuels in New England.

There on the tracks in the blinding light of the train engine, arms linked with my comrades, the sheer mass of the train and its 80 cars of coal, its immovable weight and iron force, sent a visceral sensation through my entire body. The smell of the brakes, of metal on metal, still hung in the frigid air, and the overpowering hum and vibration of the idling diesels rattled my core.

Ten thousand tons of coal, stopped by 12 human bodies—mothers and fathers, teachers, faith leaders, workers young and old—for more than an hour. How long could we have stopped it had there been hundreds of us? Thousands? What would happen if enough people refused to allow the coal trains to pass?

“Let your life be a counter friction to stop the machine,” Henry Thoreau wrote in the radical abolitionist essay we know as “Civil Disobedience.” If he only knew what the machine would do. I envy him that he didn’t.

We are now in the midst of the sixth mass extinction of species since life on this planet began—caused this time not by any asteroid or natural geological process but by humanity itself; or, more specifically, by our global fossil-fuel-driven economic system, those who make its rules, and those who profit. Scientists estimate that half of the several million species on Earth will likely face extinction before this century is out.

Of course, human life and civilization are also threatened—and not in some distant dystopian future. In many parts of the world, including parts of this country, catastrophic climate change is already here. Drought-plagued California and the Rockies are burning at an unheard-of rate. Houston has suffered five 500-year floods in five years. And as always, the poor, the racially marginalized, and the young—those who have done little or nothing to cause the catastrophe—suffer, and will suffer, most. By 2070, close to one-fifth of the planet’s land area, almost entirely in the poorest parts of the world, could be rendered uninhabitable by rising heat alone—affecting as much as one-third of humanity. More than a billion people could be forced to migrate, becoming climate refugees, by mid-century.

“I walk toward one of our ponds,” Henry wrote in “Slavery in Massachusetts,” that scathing indictment of his state’s complicity in the Fugitive Slave Law, “but what signifies the beauty of nature when men are base?”

It was not an idle question.

“Walked to Walden last night (moon not quite full) by railroad and upland wood-path, returning by the Wayland road,” Henry wrote in his Journal entry for June 13, 1851. He was given to walking at night—often following the railroad tracks through the Deep Cut between the town and Walden—and he even seemed to prefer it, his senses heightened in the dark. “The woodland paths are never seen to such advantage as in a moonlight night, so embowered, still opening before you almost against expectation as you walk; you are so completely in the woods.” And he was especially taken with the sight of the water at night, describing it in spiritual terms.

I noticed…from Fair Haven how valuable was some water by moonlight…reflecting the light with a faint glimmering sheen…. The water shines with an inward light like a heaven on earth. The silent depth and serenity and majesty of water!… By it the heavens are related to the earth, undistinguishable from a sky beneath you.

Late one night near the end of October, I followed Henry’s route, heading south down the tracks from the edge of town, through the Deep Cut, to Walden. The embankments rose steep on either side, the moon hidden somewhere behind the pines towering over me to the west, so that it was very dark as I walked, and I was glad for the flashlight and the walking stick I’d brought. Alone in the suburban woods, in deep autumn silence, I had the pulse-quickened sensation of being in the wild.

And so there I was, purposefully striding down the same railroad Henry knew, just out for a walk as if nothing out of the ordinary, until I began to think of the history the railroad held, and all it signified. I thought of the Irish laborers fleeing famine who carved that Cut and laid the tracks, and Henry’s sympathy and charity toward their families, whose shacks were built into the hillside above the cove on Walden’s northwest bank; of the Black fugitives fleeing north, whom Henry sheltered and discreetly assisted, at no small risk, onto the trains for Canada; of the Harper’s Ferry conspirator, a price on his head, whom Henry spirited out of Concord to the station in Acton the day after John Brown was hanged.

And I thought of the locomotives, the steam and the coal smoke; the coal itself, the mines, the miners; capital and labor, global industry and technological hubris; empire and oil and Anthropocene.

Half a mile down the tracks, the glow of Walden appeared through the trees, serene and unmeasurable in the distance, and I saw what Henry meant about the water at night. I made my way along the northwestern shore—owing to the drought, a narrow strip of gravelly beach rimmed the pond—the only sounds my footsteps and the sudden rustle of startled unseen creatures in the leaves, until I stood on the eastern point of the cove, looking west. I was just in time to see the moon, a waxing gibbous three-fifths full, descending into the tops of the tall pines on the steep opposite shore. There was no reflection on the water, which was entirely calm and still. Its glassy surface caught the faint light of nameless constellations.

A breeze picked up out of the north, sweeping the pond from Henry’s cove to the shore below the railroad tracks. My senses were alive and awake as I have rarely felt them, and to my surprise I had no fear of the dark.

“We do not commonly live our life out and full,” Henry writes after his night walk to Walden, “we do not fill all our pores with our blood; we do not inspire and expire fully and entirely enough.”

“We live but a fraction of our life,” he writes there. “Why do we not let on the flood, raise the gates, and set all our wheels in motion? He that hath ears to hear, let him hear. Employ your senses.”

What is my life, what am I, if not my senses, my body? And what if a life lived out and full requires the readiness to risk it, to give that life entirely, for something or someone beyond my small self, something transcendent yet from which I am not separate—another person, all other persons?

The moon was now hidden. The water at my feet was dark, deep, and clear. It was midnight, and I was alone with Walden.

—Wayland, Mass., November 2020

.