Holocaust literature at its core is inevitably Eurocentric, yet when seen globally, its geographic scope is stunning. In Latin America, for instance, a vigorous fount of memoirs, fiction, poetry, and drama has emerged over the last half-century examining the experiences and reverberations of the Shoah. For example, the Argentine journalist Jacobo Timerman’s celebrated autobiography, Prisoner Without a Name, Cell Without a Number, describes scenes of torture in which military officers proudly tell Timerman that the persecution of Jewish dissidents in Argentina during the Dirty War should be seen as an extension of the “final solution” to the Southern Hemisphere. An array of novelists and poets have explored the lives of Holocaust survivors and their descendants in Chile, Cuba, and Venezuela after the liberation of Auschwitz and other extermination camps. José Emilio Pacheco’s novel Morirás lejos, which remains untranslated into English, tells of a survivor who spots a former Nazi in his Mexican neighborhood. Jorge Volpi’s best-selling In Search of Klingsor is about Allied scientists racing against Hitler to make the first atomic bomb, while Roberto Bolaño’s Nazi Literature in the Americas offers a Borgesian encyclopedia of invented fascist writers.

While none of these have the wherewithal to change the overall narrative representation of the Holocaust, such non-European works offer a bracingly “decentralized” view of how its horrors and traumas spread out from Europe into the rest of the world. The Shoah cannot be viewed from one place or set of places: Its barbarities recognize no borders, and this is true of Latin America as well as many other parts of the globe. Even Jorge Luis Borges, the region’s leading literary dean, dedicated some of his fiction to exploring it: In his story “Deutsches Requiem,” he examines a Nazi renegade who, recognizing Germany’s defeat toward the end of the Second World War, obsesses about a Jewish prisoner, while in “The Secret Miracle,” he tells of a writer and translator who asks God’s permission to complete his magnum opus—a verse drama—as he is about to face a Nazi firing squad. These and other tales explore the implications of the Holocaust in a world where evil is anything but banal and lacks a uniquely national character.

Santiago Amigorena’s novel The Ghetto Within—his first to be translated into English—is one more addition to this sizable Latin American canon; it is also a conscious attempt at reevaluating it “from the edges,” as Borges liked to put it. A well-known French filmmaker whose Yiddish-speaking ancestors immigrated to Argentina in the 1930s, Amigorena went into exile during the Dirty War and in time became a prolific movie director, producer, and screenwriter (his two dozen scripts include Juan Diego Solanas’s Upside Down and Jonathan Nossiter’s Last Words). Yet what Amigorena considers most essential in his oeuvre are his works of fiction. He is the author of a dozen books that constitute a unified project about the echoes of the Shoah in France and Argentina, which is designed, he tells us, to “oppose the silence that has stifled me since birth.” In a brief preface, Amigorena states that The Ghetto Within is “the source” of that project: his effort to consider the dark shadow that the Holocaust has cast not only on Europe but on Latin America. By zooming in on Polish Jewish refugees who seek to assimilate in Buenos Aires—“the Paris of the Southern Cone”—by distancing themselves from the atrocities unfolding far away in Europe, he also hopes to rethink the Shoah canon, studying how the genocide reverberates to the farthest corners of the globe.

The Ghetto Within tells the story of Vicente Rosenberg, an assimilated Polish Jew who immigrates to Buenos Aires, where he grows even more disengaged from his Jewish heritage. A Yiddish speaker, Vicente studied law at the University of Warsaw, although his true passion is German poetry, especially Goethe, Schiller, Hölderlin, Novalis, and Heine. Disoriented at first in his new country, he eventually finds support in the friendship of two other Polish Jews, Ariel Edelsohn and Sammy Grunfeld, and falls in love with Rosita, also Jewish, whose parents arrived in Argentina a couple of decades earlier. After a while, Vicente and Rosita marry and have three children: Martha, Ercilia, and Juan José (aka “Juanjo”). But Vicente is unhappy, without a goal. As a way to make his son-in-law less volatile and more financially stable, Rosita’s father brings him into his furniture business. By the late 1940s, the family has moved comfortably into Argentina’s middle class, where, as it happens, some 240,000 Jews live today, the second-largest concentration in the Americas after the United States.

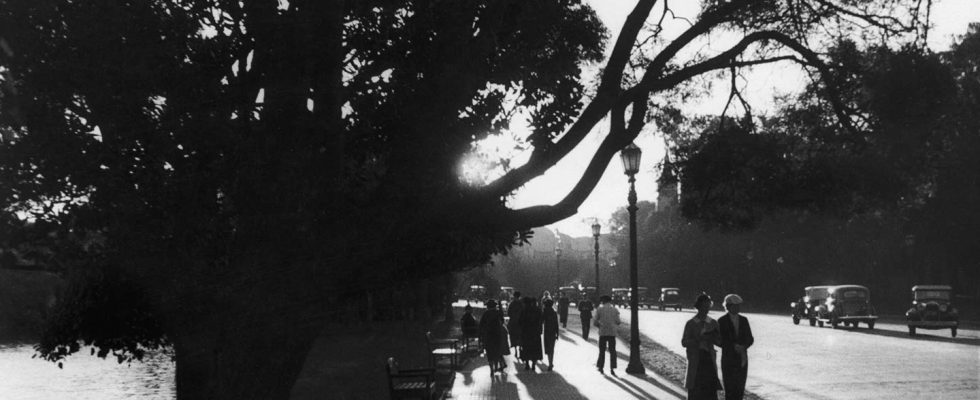

In typical porteño style, Vicente spends an exorbitant number of hours talking with Ariel and Sammy at the Café Tortoni, a famous European-style coffeehouse where, Amigorena writes, in September of 1940, “one was as likely to encounter Jorge Luis Borges and the glories of tango as European refugees such as José Ortega y Gasset, Roger Caillois, or Arthur Rubinstein.” In these encounters, which make up a generous portion of the novel, Vicente discusses the events connected with the war unfolding in Europe at the time. A parallel plot thus develops, as Vicente’s mother, Gustawa Goldwag, and his older sibling are rounded up in Warsaw by the Nazis and isolated in the ghetto on the banks of the Vistula River, where the living conditions rapidly deteriorate. An assiduous letter writer, Gustawa has asked her son, before his departure to Argentina, to promise that he will write to her once a week. But as a busy entrepreneur with a budding family, Vicente comes up with all sorts of subterfuges to avoid keeping his promise. His mother’s letters are quoted in full in the novel, followed by long paragraphs describing Vicente’s remorse at having fallen into a silence that, as in the case of the book’s author, asphyxiates him.

In his furniture store, Vicente hires a salesman who is a communist immigrant from Germany. The salesman comes to see Vicente as a father figure, and their relationship allows Amigorena to test Vicente’s views on Germany on a more human level. Although he intensely hates Hitler, Vicente loves German culture, and through his relationship with the salesman, Vicente wrestles with this love. Thanks to an unexpected visitor from his Polish past, as well as through newspapers like La Nación, the Argentine Jewish community’s Zionist organ La Idea Sionista, and London’s Daily Telegraph, which always arrives in Buenos Aires several weeks late, Vicente finds out about the genocide in the Łódź ghetto and the degree to which starvation has decimated the people in the Warsaw ghetto, including members of his own family. Guilt-ridden, he becomes more and more taciturn, even ghost-like, until he ceases to communicate with his wife, children, and friends altogether. Words are no longer suitable to convey Vicente’s immense agony. But suddenly, as if in a desperate search for hope, Rosita gets pregnant again.

The reader never learns the details of Vicente’s mother’s death, other than that, after the uprising in April 1943, the Nazis flattened the Warsaw ghetto. There are extended portions of The Ghetto Within that provide historical details about the Nazis’ plan to build extermination camps in the East, which are inserted as if they were taken, unprocessed, from Wikipedia. There are also rambling sections about the Wannsee Conference, where “the final solution to the Jewish question” was formulated in discussions between Hermann Göring and Adolf Eichmann, among others. And there are long-winded passages on semantics, as in the debate around the word chosen to describe the Nazis’ attempted extermination of the Jews, going back and forth between “holocaust,” “genocide,” “cataclysm,” “hecatomb,” “apocalypse,” and the Hebrew shoah and khurban.

Amigorena is intent on fitting the plight of his characters into the historical context, but he is no Tolstoy, Mary Renault, García Márquez, or Hilary Mantel. Along the way, he misses juicy opportunities. For instance, Vicente, before moving to Warsaw, is raised in a shtetl called Chelm. I’m not sure Amigorena is aware of the enormous role that a mythical “Chelm” plays in Yiddish folklore, known to be where Jewish fools inhabit. It might be just an aside to him, yet it signals the degree to which he has only half-digested the culture he is depicting. Mostly, though, The Ghetto Within appears to be an attempt—and no doubt a worthy one—to bring to the fore questions of anti-Semitism and identity in France today (where Amigorena lives), as the conditions of Jewish life become increasingly fragile. This is a typical passage:

One of the most pernicious things about anti-Semitism is the refusal to allow certain men and certain women to ever cease to think of themselves as Jews, to confine them to this identity against their will—to decide, definitively, that this is what they are. Vicente did not feel as if he had been gifted something, that he had had his mind opened, that he had been enlightened as to what he was or who he was. He did not think: at least now I know that I am a Jew. Vicente, like many Jews, was merely beginning to understand that, in order to exist, anti-Semitism needs Semites; he was beginning to realize that, if an anti-Semite defined himself as such, he can no longer tolerate that a Semite not define himself, since he is one.

This disquisition is obviously in debt to Jean-Paul Sartre’s book Réflexions sur la question juive (known in English as Anti-Semite and Jew), in which Sartre argues that anti-Semites need Jews to exist, but that Jews need anti-Semites just as much, to remind them of who they are. Whether this is true is another matter: To view anti-Semitism as a call-and-response phenomenon risks the possibility of making antagonism the rule of all identities. Jews, in countless historical periods, have existed outside an ecosystem that rewards hatred.

Unfortunately, these philosophical questions do not appear in The Ghetto Within, and one wishes the book offered a more probing examination of the varieties of anti-Semitism that proliferated in Argentina at the time. In the mid-’40s, Germanophilia swept the intellectual circles of Buenos Aires; Borges reflects on it in one of his essays. Likewise, one wishes that the varieties of Jewish life in Latin America were also captured beyond the setting of this reductive form of anti-Semitism. Buenos Aires in 1943 suffered a coup d’état: One of the military figures behind it was the fascist-leaning Pedro Pablo Ramírez Menchaca. There was a considerable German community in Argentina with roots reaching back to the 19th century, and a portion of it embraced the surging fascist movement in Buenos Aires and elsewhere. The dissemination of pamphlets like The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was extensive. Meanwhile, Jewish activists and writers like Alberto Gerchunoff, Carlos Grūnberg, and Lázaro Liacho gave voice to the anxiety that Argentina’s Jews were undergoing. Amigorena makes little to no mention of these local events. It is as if his plot unfolded in a vacuum.

In the end, things are conveniently wrapped up in The Ghetto Within when, in a 180-degree narrative turn offered in the last chapter, we are told that Vicente and Rosita’s middle child, Ercilia, is Amigorena’s mother, and thus the story we’ve been following is that of the author’s grandparents. Amigorena quotes Theodor Adorno, who argued that “to write poetry after the Holocaust was barbaric”—only to reconsider and return to writing:

Does the Shoah have a definitive quality? I find it difficult to say that anything has a “definitive” quality. Like Pythagoras, like Borges, I prefer to think that things cyclically return. Anti-Semitism forced my forebears to leave Europe. Latin American dictatorships forced me to flee Argentina and later Uruguay with my parents—to return to Europe. I was forced to leave my country, my mother tongue, my friends. Like my grandfather, I was a traitor: I was not where I should have been.

Intriguingly, Amigorena mentions that his cousin Martín Caparrós, a prominent Argentine journalist who has written an incisive book on world hunger—and who is also the oldest son of Vicente and Rosita’s first child, Martha (he is known in the family as “Mopi”)—has also surveyed Gustawa Goldwag’s odyssey. In a personal essay called “Los Abuelos,” Caparrós states that for years he considered the Holocaust “only from afar,” through studies and accounts, films and photographs. But then he realized that his great-grandmother died in the Warsaw ghetto, and things changed in that instant: This is “the story of my blood,” he confesses.

As a result of their diasporic wanderings, Caparrós and Amigorena have arrived in the same place through forking paths. One writes in Spanish, from Argentina, the other in French, from France, but the Holocaust is a personal obsession for both. Having digested it through Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl, Primo Levi’s Survival in Auschwitz, and Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem, they have made it central to their lives, although they delve into it obliquely, from a slanted geographical perspective. In doing so, they reinvent a past that is long gone, and a past that is now theirs only peripherally.