To help him decide, MacFadyen had a set of small glass hydrometers that measure density; by indexing density and temperature, using a crumbling reference book from 1978, he could identify the percentage of alcohol in a sample. He opened a brass case marked “spirit safe,” inside of which there was a constant stream of spirit, pouring from a metal spout. He dipped a glass into the stream. What he caught didn’t taste like whisky at all—it was slightly smoky and sweet, with a faintly unpleasant sharpness, like fermented NutraSweet. It would be inaccurate to call this clear spirit undrinkable; up until the nineteen-seventies, distillery workers were customarily given drams of clear spirit before, after, and sometimes during their shifts.

Many whiskeys are purer than Scottish malts. Irish whiskey is customarily distilled three times, instead of two; grain whisky, like vodka and gin, is often produced using a reflux still, which can turn wash into a distillate that is about ninety-five per cent alcohol. But impurity is what gives whisky its flavor: all sorts of chemicals, known as congeners, survive the still. “Malted barley, distilled, is the most complex spirit in the world,” Reynier says. “It’s got too much flavor.” Whereas American bourbon, by law, must age in new oak casks, Scotch distillers prefer used casks (typically bourbon), partly because they are less reactive—vanillin and other oaky compounds don’t overpower the spirit. The purpose of maturing Scotch is to enhance the strong flavors that remain after its relatively tolerant distillation process, and tame them, too. Even Reynier agrees that some taming is required; he just doesn’t believe that tamer is always better.

In 1703, a Scottish writer named Martin Martin published “A Description of the Western Islands of Scotland.” In his discussion of Lewis and Harris, the northernmost island in the Hebrides, he made tantalizing reference to a whisky-like beverage, made from oats and quadruple-distilled, which he called usquebaugh-baul: “usquebaugh” means “water of life,” or “eau de vie”; “baul” may have referred to its potency. Martin concluded his description with a firm prescription: “Two spoonfuls of this last Liquor is a sufficient Dose; and if any Man exceed this, it would presently stop his Breath, and endanger his Life.” To Reynier and McEwan, Martin’s prescription seemed like a dare, and they set out to create their own version of usquebaugh-baul, a name they translated as “the perilous whisky.” Bruichladdich put out a press release announcing the “most alcoholic single malt ever made”—the unmatured spirit was about ninety per cent alcohol. Within a few days, the story of the death-defying whisky was in newspapers around the world. The Scotch Whisky Association—a powerful trade group, which Reynier refused to join—issued a statement saying, “Undue emphasis on high alcohol content is irresponsible and should not be used as the principal basis of any product’s appeal to the consumer.” Bruichladdich’s Web site defiantly reminded visitors of the S.W.A.’s verdict: “irresponsible.” Oz Clarke, the wine critic, tasted the unmatured spirit on a BBC program. He delivered his verdict with eyes closed and shoulders hunched: “Oh! Oh.” James May, from the beloved automobile show “Top Gear,” used it to fuel a racing car. By the time the spirit had matured, it wasn’t quite so radical: Bruichladdich aged it in bourbon casks for three years, and then sold a few thousand bottles, at a strength of sixty-three and a half per cent alcohol—not quite perilous but still strong.

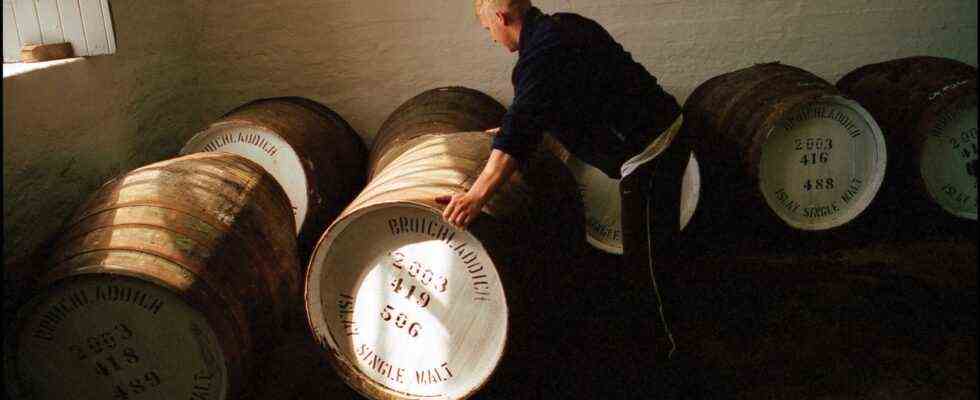

Throughout the aughts, Bruichladdich was both more and less old-fashioned than its competitors. It refused to artificially color its whisky, or to chill-filter it; chill-filtration removes oils that can cause cloudiness but which also impart flavor. As part of its program to emphasize ingredients over age, it released a series of barley-specific whiskies: one was made solely from organic barley; another was made from bere, an ancient cultivar that could have been brought to Scotland by Vikings in the first millennium. The distillery persuaded some local farmers to start growing barley, so that, for the first time since the First World War, consumers could buy Islay whisky made from Islay barley. Bruichladdich never figured out a cost-effective way to malt barley on the island—all its barley is sent to a huge malting plant in Inverness, in the Scottish Highlands, which returns malt imbued with a specified amount of peat smoke. (McEwan says, “You’d need malt barns the size of Terminal 5, Heathrow Airport, to supply a modern distillery.”) But just about everything else is as local as possible. The distillery even runs its own bottling hall: all year long, bottles are shipped in by ferry from the Kintyre Peninsula, filled and labelled, and then shipped back out.

All this localism has helped make a rather small distillery the biggest private employer on the island: out of Islay’s thirty-five hundred residents, about fifty of them work for Bruichladdich. The island is an appealing place to vacation; its part-time residents include Sir John Mactaggart, the Scottish real-estate mogul, and Bruno Schroder, the banking billionaire. (Both of them invested in Bruichladdich.) But the trickle of retirees from the mainland has not kept pace with the exodus of islanders looking for work; the population is barely half what it was fifty years ago. Most farmers on the island supplement their earnings with government subsidies, paid to follow various environmental strictures or merely to maintain farms in such an inaccessible place.

One of Bruichladdich’s most valuable local assets is a burly and charismatic gadabout named James Brown, widely known as Farmer Brown. He is sixty years old and vigorous: an ex-lighthouse keeper, a former special constable, a passable bagpiper, and, by all accounts, a pretty good tosser of hammers. His farm, a few miles down the road, sits on the site of a long-gone distillery called Octomore, for which Bruichladdich’s ultra-peated whisky is named. Some of Bruichladdich’s barley comes from Brown’s farms, and although, like most islanders, he is no connoisseur, he has amassed an impressive collection of Bruichladdich whisky—unopened bottles accrue in his house, shoved in filing cabinets and stacked precariously in corners. “If we’re drinking whisky up here,” he says, “we take the cork off the bottle, and it’s—pfft. And get another bottle. None of that nonsense of wee sips.”

Brown is also the de-facto administrator of Dirty Dotty’s spring, the source of the water that Bruichladdich uses to bring its whisky down from cask strength to bottling strength, which is generally forty-six per cent alcohol. Brown remembers the day when Reynier and a few other Bruichladdich executives arrived on his property with wineglasses, to evaluate the water from his spring. They liked it, and asked for six barrels, leaving Brown to figure out how to get it to the distillery.

One autumn morning, Brown was preparing his weekly delivery. The weather was typical: about forty-five degrees and almost raining. “Couldn’t be nicer, eh?” Brown said. He had driven his tractor half a mile up a dirt road; from where he parked, you could see his Highland cows grazing on the sloping fields and, beyond that, the gray stucco of the North Atlantic. Brown grabbed one end of a hose and scrambled down the hill toward a tiny shack, recently built from unpainted pine, that stood next to a stream. “That water there is black,” he said, pointing to the stream. Then he opened a trapdoor in the floor of the shack and lowered a cup on a string; when he brought it back up, it was full of clear water that bore no trace of peat or salt. “That water there comes out of the ground,” he said. “The second-oldest rocks in Europe.” Jerking hard on a starter cord, he coaxed a gas-powered pump to life; it takes him about an hour to fill a thousand-litre plastic tank, and Bruichladdich was expecting six of them.

It’s not clear whether even the most refined palate could correctly judge the age of gneiss rock by sampling the springwater that flows through it, but Bruichladdich isn’t inclined to let any superlative go to waste. One of the company’s most popular whiskies is its cheapest, Bruichladdich Rocks, which promises to let consumers commune with “the oldest rocks in the whisky world!” Bruichladdich Rocks doesn’t carry an age statement, but it is about six years old, and it spends its final few months of maturation in red-wine casks, which give the spirit a sprightly, pleasantly acidic taste. McEwan speaks fondly of it, but he doesn’t deny its purpose. “Rocks—that was just a young, non-aged whisky that we put on the market, that was kind of taking the heat off the older stocks,” he says. “People said, ‘Ah, Bruichladdich are doing so many different things.’ Yeah, well, we had to! If we didn’t, we’d have been sitting there starving—the company would never, ever have got off the ground.”

In 2011, the new Bruichladdich turned ten, and so did the oldest batch of new whisky in the warehouse. The distillery finally had a flagship ten-year-old, which it called the Laddie Ten: a definitive name for a definitive dram. Bruichladdich even allowed itself to gloat, with a slogan: “The first ten years are the toughest!” Reviews were generally enthusiastic. Whisky Advocate named the Laddie Ten the year’s best Islay whisky, above bottles that sell for more than ten times the price. (In the U.S., a bottle of the Laddie Ten costs about fifty-five dollars.) And, for the first time, Bruichladdich appeared on the shelves of duty-free shops in airports worldwide.

The success of the Laddie Ten seemed to mark Bruichladdich’s transformation from scrappy upstart into successful mainstay, and the impression was confirmed last summer, when the company made a startling announcement: it was selling out to Rémy Cointreau, the French liquor conglomerate, whose products include Rémy Martin cognac and Cointreau liqueur. (The price was fifty-eight million pounds, including ten million pounds of assumed debt.) Out of Bruichladdich’s eight board members, only one voted against the sale: Reynier. Once the deal was struck, Reynier was asked to leave, and was replaced by his longtime business partner Simon Coughlin. Reynier announced his departure on Twitter: “Over & out.” In his next post, he filled in a few details: “(it’s) over & (I’m) out (of here).”

Reynier now lives in Edinburgh, where his son goes to school, but this fall he was back on Islay for a few days. In his old office, he seemed slightly disoriented—he still thinks the sale came too soon, and he hasn’t shed his habit of talking about Bruichladdich in the first-person plural. “Just being in this office is strange,” he said. “This is where I’ve lived for the last eleven years.” All around the distillery, nothing had changed, with one small exception. On the antique Ford pickup truck in the courtyard, a wooden sign above the windshield read “1881 Bruichladdich 1881.” In recent months, someone had added a new wooden sign, above the old one: “2012 Rémy Martin 2012.”

Simon Coughlin, the new chief, says that Rémy is an ideal parent company, because it allows subsidiaries to operate with relative independence. “We’re the experts about Bruichladdich,” he says. “And they’re bloody good listeners.” During Bruichladdich’s first decade, it didn’t have the marketing budget or the distribution power to find a place in any but the most ambitious bars; it had to rely on its bright-colored tins and daunting variety to stand out on liquor-store shelves. Now the company will have access to Rémy’s international distribution network; in the U.S., Rémy distributes Macallan, which is ubiquitous. With money from Rémy, Bruichladdich plans to add an overnight shift, and double production, to one and a half million litres a year.

Coughlin wants to streamline Bruichladdich’s offerings, but not in the way many industry observers would have predicted. He now describes the grand celebration of the Laddie Ten as, in some ways, a distraction from the company’s true strength. “I think that we got drawn, a little bit against our true feelings, into age statements,” he says. “So there’s going to be less emphasis on age statement. And there’s going to be more emphasis on the barley than there’s ever been.” In other words, the new new Bruichladdich will be much like the old new Bruichladdich—only more so.

Anyone considering the future of whisky on Islay should visit Caol Ila (“Cull-ee-lah”), which produces six million litres of liquor per year—more than any other Islay distillery—with only eleven full-time employees. At the depopulated stillhouse, in a preposterously scenic spot on the coast, the gift shop sells bottles of twelve-year-old Caol Ila, described as a “secret malt,” produced “in a remote cove.” The only hint of the distillery’s true identity can be found on the tote bags for sale, which include its e-mail address: [email protected]. Diageo is the dominant player in the Scotch industry: it owns twenty-eight distilleries and makes dozens of blended whiskies. The most important of these is Johnnie Walker, which accounts for about twenty-two per cent of the whisky sold worldwide. The main reason that Caol Ila remains “secret” is that most of what it produces ends up in Johnnie Walker and other blends; less than five per cent is sold as single malt.

In an economic sense, Caol Ila’s picturesque location is mostly wasted, especially since its whisky is shipped back to the mainland to mature. Malted barley can be distilled anywhere: Japan has a thriving single-malt industry, and a number of distillers in the U.S. are making Scottish-style whisky. Distillers in Japan and America can’t call their products Scotch, but there’s nothing stopping a company like Diageo from closing down its Islay operations and moving them to Glasgow or some other, more convenient location. (Just about any location would be more convenient than Islay.) In 2010, Diageo opened a large-scale distillery called Roseisle, in northern Scotland, which produces about ten million litres of alcohol per year, all of it for blend.

Reynier thinks he knows where this is leading. He imagines an accountant at a big liquor conglomerate suddenly wondering, “Why do we have distilleries on these remote Hebridean islands?” The Scotch Whisky Association recognizes five kinds of Scotch, one of which is “blended malt”—that is, a blend of malt whiskies from two or more distilleries. To Reynier, this seems intended to make it easier for big companies to do away with small distilleries, while still claiming to sell malt. “The distilleries that are left will be façades—for marketing,” Reynier says. “And the actual spirit will all be distilled somewhere else. No doubt.”

McEwan is less worried; he thinks that rising demand, particularly from Asia, will only make great malt more valuable. “I can rest easy in my chair,” he says, “knowing that I have helped to provide a secure future for generations, possibly.” Because single-malt whisky is a luxury product, its makers can afford to ignore some of the demands of efficiency—in fact, Bruichladdich has proved that some whisky drinkers will pay a premium for whisky made in unusually inefficient ways. For the purpose of keeping far-flung distilleries afloat, Bruichladdich’s business model might be the only one that makes sense. By making the Islay terroir a central part of its brand, Bruichladdich has made itself essentially immovable.

Already, there are signs in the industry that Bruichladdich has been influential—or, at the very least, prescient. More companies now sell whisky that is uncolored and un-chill-filtered, and some now offer whisky aged in a variety of casks. Demand is rising faster than distillers had predicted; as aged stocks deplete, a growing number of distilleries are promoting whisky with no age attached. Last year, Macallan announced that all its malt younger than eighteen years old would be sold not by age but according to a four-color system, ranging from gold to ruby. By law, age statements must reflect the age of the youngest spirit in the bottle; forgoing them gives distillers more flexibility, allowing them to combine malts of different vintages, some of which might be recent. This approach also demands a certain amount of faith from consumers, who have learned to be skeptical of vague claims on whisky bottles. But, then, for anyone who loves malt, there is no alternative to faith: if you don’t trust the distiller, nothing written on the bottle will guarantee you a great dram.

It was late afternoon in the Bruichladdich gift shop, and McEwan was waxing ambassadorial. Some guests were in town from Japan—bar and restaurant owners, all current or potential customers—and tables had been set up for a formal tasting: white tablecloths, rows of glasses, and a handsome bound book of tasting notes.

Few of the guests spoke English, and so McEwan had to pause between phrases for the translator, which made him sound even more theatrical than usual. Assistants poured out small drams of the Laddie Sixteen, which was made from spirit distilled by the previous regime. McEwan said, “If I was asked, ‘What was the last whisky in the world, before you die, which one would you have?’ ” He slapped his hands together. “Sixteen.” As the guests sipped, he supplied some real-time tasting notes. “It’s a little bit spicy,” he said. “If you add a little bit of water, then you get the apricot, the peach, the pear—maybe a little bit of gooseberry.” There was some stammering from the translator as she tried to summon the Japanese word for “gooseberry.”

.