In the Season 2 opener of the OWN drama Queen Sugar, a teenaged Micah West (played by Nicholas Ashe) is pulled over in his luxury sports car for what appears to be an instance of driving while Black. After he’s released into the custody of his parents, the estranged couple argues in the parking lot. Meanwhile, when Micah’s Aunt Nova (Rutina Wesley) comes to comfort him, she notices that the boy has urinated on himself. “Ain’t nothin’ to be ashamed of,” she tells him, embracing her nephew while discreetly tying her sweater around his soiled pants. It isn’t until Episode 8 of the season that viewers discover what really happened: A still-traumatized Micah tells his father that before going to the precinct, the police officer drove him to a dark alley. The officer put what turned out to be an unloaded gun in the boy’s mouth and pulled the trigger, informing Micah that he hates privileged, “fancy-talking niggers.”

“I think, for other shows, it would have been ‘a very special episode of Queen Sugar about police aggression,’ but for our show, [that arc] lasted for two seasons,” the creator, Ava DuVernay, told me. “We never forgot that this had happened to him, because he would have never forgotten it.” That extended story line explored police violence and the lingering effects of trauma on the show’s central family, the Bordelons, as Black Lives Matter protests erupted around them. It was groundbreaking television. This week, Queen Sugar returned for its seventh and final season, making it one of the longest-running Black family dramas in television history. Since the show’s 2016 debut, loyal Sugar viewers have followed the lives of siblings Nova, Charley, and Ralph Angel Bordelon—as well as their children; their Aunt Violet; and her husband, Hollywood—as they’ve fought to maintain ownership of their family’s 800-acre Louisiana sugar-cane farm. Over the show’s run, critics have praised it for being sexy and engrossing. They’ve also applauded DuVernay’s choice to hire an all-woman directorial team—several members of which had never before directed scripted TV—to help tell this story about race, class, and inheritance in the U.S. South. With its cinematic visuals and deep attention to the particularities of Black life, Queen Sugar has reimagined what television about the American family can look like.

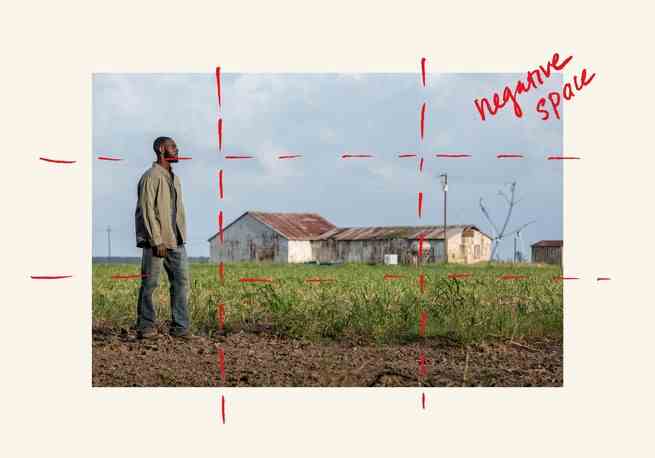

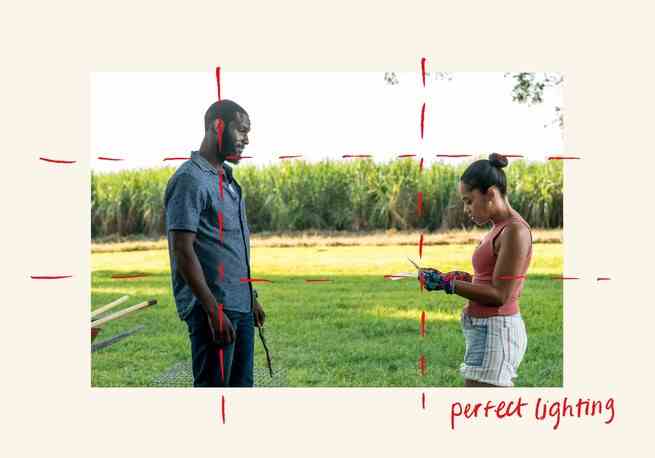

The intentional storytelling that distinguishes Queen Sugar from other TV dramas is what DuVernay terms “luxurious pacing.” The show adheres to a three-act structure more typical of films instead of TV’s usual five-act format—the latter’s design is well suited to ending each act with a cliff-hanger before the commercial break. Consequently, Queen Sugar episodes might have fewer moments of heightened action, but they still effectively build and sustain emotional tension across the breaks. This technique creates what feels like loping narrative strides that unfold into bursts of Black joy, even as the show takes on the most wrenching subject matter. Visually, the show heavily utilizes what the crew calls the “Queen Sugar frame,” or shots where an actor is isolated at the edge of the frame. The abundant negative space around the actor captures the Louisiana environment: the chartreuse and forest-green hues of the sprawling Bordelon farm, the muddy browns of the waterways, and the multicolored shotgun- and bungalow-style homes characteristic of Louisiana architecture. An editorial pattern that resists quick cuts allows scenes to linger, to capture what DuVernay calls the “gentle moments,” the subtle glances between characters, as the lighting perfectly hits their melanated skin. “Black people in their everyday lives should be shot with cinematic grandeur,” said DuVernay, who collaborated with the cinematographer Antonio Calvache to develop the show’s lighting direction.

In the United States, family dramas on television offer fictional representations of shared American values. They typically center on one family to explore how its members collectively handle real-life issues such as divorce, sibling rivalry, and unemployment. Programs from The Waltons and Little House on the Prairie to 7th Heaven and Parenthood have become blueprints for the genre. Each show has its own bent, but themes of hard work, economic stability, and heteronormative relationships are universal. Reflecting notions of the American Dream makes these shows relatable and trustworthy for mainstream viewers while reifying the notion that the ideal American family is white. Many recent dramas, such as the Freeform (formerly known as ABC Family) show The Fosters and NBC’s This Is Us, offer a progressive take on the formula but still work within the established parameters of the genre. Since the 1970s, there have been dozens of dramas that center on white families. Conversely, before Queen Sugar, there had been only a handful of Black family dramas on network and cable television, including CBS’s Under One Roof (1995), Showtime’s Soul Food (2000–2004), and the ABC Family vehicle Lincoln Heights (2007–2009).

Historically, Black family shows have either been sitcoms, such as The Cosby Show (1984–1992) and Black-ish (2014–2022), primetime soap operas such as Empire (2015–2020) and OWN’s Greenleaf (2016–2020), or crime dramas such as Power (2014–2020). One interpretation is that many studio and network executives don’t believe there’s an audience for a Black show that revolves around something other than humor and violence. Others might not believe Black stories are suited to the sensitive, character-driven work of the family drama. Such beliefs may stem from the myth of the pathologically dysfunctional Black family that has persisted since the era of U.S. slavery. Politicians and lawmakers codified racist and sexist tropes about African American family life in welfare and education policies, aided by sociological reports such as Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s The Negro Family: The Case for National Action (1965). African American families, particularly single-mother-headed households, have been criminalized by the media and depicted as less redeemable than even dysfunctional white families (think the Gallaghers on Showtime’s Shameless).

Queen Sugar’s method of luxurious Black storytelling eschews the conventions of the mainstream family drama and the racial hierarchy that defines the genre. DuVernay told me she didn’t consult or study any white family series while developing the treatment and pilot for Queen Sugar. She instead took inspiration from films that emerged from the so-called L.A. Rebellion movement, which was known for works such as Haile Gerima’s Bush Mama (circa 1975) and Sankofa (1993), Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1978), and Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991). Many indie filmmakers of this era resisted the conventions of Hollywood films to tell distinctive, honest stories that focused on working-class Black people. The directors blended elements of documentary, neorealism, and nonlinear storytelling with West African knowledge systems and cultural practices to explore the possibilities of Black world-making in the Americas. DuVernay hired Dash to direct the two-part midseason premiere for Season 2, which delved into the emotional burden of secrets and shame. Borrowing from Black experimental film enables Queen Sugar to depict the African American family authentically, with all its strengths and imperfections and without catering to a white audience.

Viewers can especially see the influence of L.A. Rebellion–era cinema in Queen Sugar’s Season 4 finale, which was directed by the Black indie filmmaker Ayoka Chenzira. In Season 1, viewers had learned that Nova is a rootworker, a traditional healer. She inherited her spiritual gifts from her deceased mother, Trudy Lavoisier Bordelon, whom Nova describes as a “a voodoo priestess from the bayous of Louisiana.” This rootwork arc spans several seasons. Viewers regularly see Nova engaging in what scholars such as Kinitra Brooks term “conjure feminism,” or the practice of using ancestral knowledge of West African and Caribbean herbal medicine and spirit work, to treat members of her community. Near the end of Season 4, Nova acquires from a family elder her mother’s journal, which contains Trudy’s formulas for medicinal elixirs and salves and cleansing smudges. Nova learns that her father, Ernest Bordelon, secretly buried Trudy in an unmarked grave on the Bordelon land. In the finale, Nova and her brother, Ralph Angel (Kofi Siriboe), find their mother’s burial location by deciphering her journal. The closing scene shows Nova leading her family—dressed in all white, common ritual attire in African diasporic religions—in a burial service for Trudy. In a voice-over, Nova says: “Our land … upholds our family, our hopes, and our fears … our blood and our blessings.” The land symbolizes the ancestral covenant, which predates slavery and defies Western notions of kinship, consecrating the bonds of the Bordelon family.

Indeed, the Bordelons’ land is a character in the show. It is used to historicize the conflict between the family and their nemesis, the white Landry/Boudreaux family. The siblings learn late in Season 1 that their ancestors had been enslaved by the Landrys, and later were exploited as sharecroppers until they were able to buy the land during the Great Depression. Ever since, the clans have been warring over the property rights. Thus, viewers are forced to reflect on institutional racism and the vestiges of slavery. They also witness a multigenerational Black family using land to imagine a more democratic future, one where African American farmers can profit from their own labor. In the show’s vision, true inheritance isn’t just about accumulating wealth, it’s about love for community and mutual aid. Queen Sugar “is so born out of love, pure love, in my own heart for southern traditions, and southern ways, and southern value systems,” Oprah Winfrey, an executive producer on the show, told me. She explained that they were intentional about hiring New Orleans natives as supporting cast and crew members, whose own life experiences, growing up on Louisiana soil, could add texture to the storytelling.

Season 6 ended with the Bordelons facing a major conflict: Should they accept the Landrys’ crooked deal to get the Bordelon family’s land back, or should they press forward with the other Black farmers on the co-op land deal that Ralph Angel and his wife, Darla, had proposed? Watching the Bordelon siblings confront this defining question will make for an intriguing final season. “There’s lots of little Easter eggs for the fans,” Season 7’s showrunner, Shaz Bennett, told me. As the Bordelon’s legacy unfolds on the screen, so does the show’s legacy. To see a Black, rural Louisiana family “given the care and treatment of a [Martin] Scorsese movie … just that alone, I think, is going to live a long time,” Bennett said. For now, as Season 7 takes off, longtime fans of the show can look forward to indulging in this last gift of Sugar.