Jon O’Brien’s son, Jack, was on the type of summer-long Euro trip that marks an end to late adolescence and a step into early adulthood. Jack was 25; the seven-week trip was the longest he had been away from his parents. His travels included a road trip around Iceland, a train ride through Russia with stops in Moscow and St. Petersburg, and a visit to the Camp Nou soccer stadium in Barcelona. In mid-July 2014, Jack arrived in Pamplona, Spain, to take part in the annual running of the bulls, testing his daring and athleticism on the city’s cobbled streets. Jon scoured the internet for information on the number of injuries and fatalities related to the event as soon as his son told him of his plan.

In the early evening, when Jon was still at work in Sydney, his phone buzzed with a text message from Jack. “Did the bull run,” it read. “I’m alive. Rest easy.”

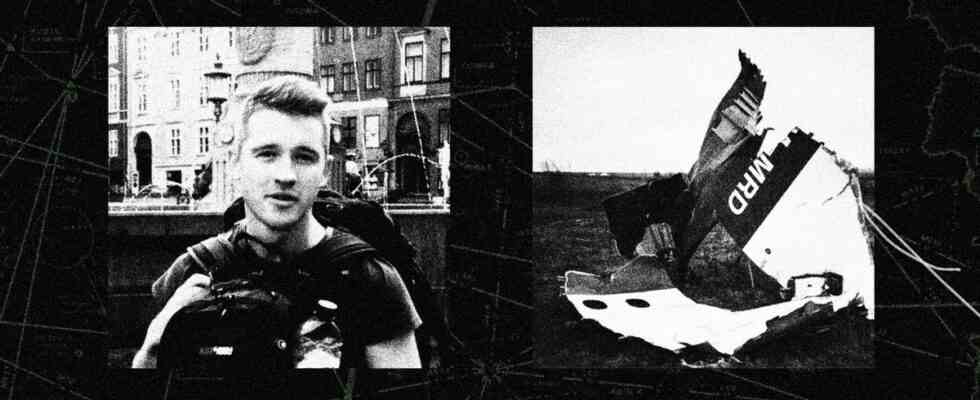

Jon was hugely relieved. The dangerous part of Jack’s trip, he thought, was over. Reports in The Sydney Morning Herald about Russian-backed incursions into eastern Ukraine had hardly registered with Jon or his wife, Meryn. In the spring of 2014, pro-Russian separatist rebels had begun seizing territory in the region, leading to an escalating armed conflict on the ground. A few days after the dash in Pamplona, Jack sprinted through Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport to catch Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17 heading to Kuala Lumpur. From there he would continue home to Australia. Jon and Meryn had made plans to meet him at the airport.

The Boeing 777 on which Jack was traveling with 297 others never reached the runway in Malaysia. It returned to earth instead in pieces, strewn across a field in eastern Ukraine. Jon and Meryn learned what had happened from a news bulletin on the radio, a moment Jon likens to a “hammer blow, straight off.”

Nearly a decade on from the disaster, Jon and Meryn are awaiting judgment from a court in the Netherlands. Among the 298 passengers and crew members who died, the majority, 196, were Dutch nationals. The flight had been under way for about three hours when it lost contact with air-traffic control in eastern Ukraine. Some airlines had already started rerouting flights because of their risk assessment of the fighting in the region, but the Malaysian flight was in airspace then still deemed safe by international aviation authorities.

Russia has always denied any involvement in the crash. Much of the early reporting on Russia’s role in the disaster was conducted by open-source investigators who combed through photos and videos posted to social media, piecing together the movements of the Russian Buk surface-to-air missile system used to shoot down the plane. Particularly instrumental was the work of Bellingcat, a website that the British journalist Eliot Higgins had established just days before the crash. Much of what the site uncovered about Russian involvement was later confirmed by the official international investigation into the downing.

Four men, all pro-Russian separatists, face charges because, prosecutors have argued, they “cooperated closely to obtain and deploy” the missile system used to shoot down the plane. Three are Russian, and the other is Ukrainian. None has surrendered to the court, and only one of the men has put up a defense at trial, pleading not guilty via recorded video messages.

The full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine earlier this year has directed far greater global attention to the belligerence of Moscow and President Vladimir Putin. For the O’Briens, that new notice has left them contemplating how the death of their son eight years ago fits into the war raging today.

“Our son was killed in Russia’s war on Ukraine, in the early days of that war,” Jon told me, when we spoke recently. “It is the same war,” Meryn interjected. “There is a direct line from July 17, 2014, to the day in February this year when Russia invaded.”

Jon and Meryn started a website where, with the help of one of Jack’s friends, they occasionally post updates and share memories of Jack. Jon wrote about the love of soccer he and Jack shared, and about Jack’s fandom anxiety from following the ups and downs of Australia’s national team. “I would say my biggest passion is soccer,” Jack wrote for a job application in 2012 that appears on the site. “I have played since I was 7 and will continue to till I’m 70.” Jack had finished a degree in business and was studying to become a personal trainer. Before his European trip, which he took with a childhood friend, Jack had started to gather his belongings for a planned move, away from his apartment behind his parents’ home and into a new one with a roommate. “He was coming back to get on with the rest of his life,” Jon said.

Because the site is quite basic and infrequently updated, it’s not all that easy to find by search. I found an email address linked to the site’s registration and wrote to it a few days before July 17, the eighth anniversary of the MH17 disaster. When I got a reply from Jon and Meryn, they said that they would be happy to talk with me, but the immediate timing was hard for them. “Our sadness for Jack is seeping to the fore at this time,” Jon wrote.

When we did speak, not long after the anniversary, I was struck by how friendly the O’Briens were and how remarkably collected despite the “wound that will never heal.” At times, they differed over the exact details of the days surrounding Jack’s death, such as who was planning to take the day off to meet him at the airport. The good-natured quibbling was almost the same as you’d hear in the retelling of a favorite family story around the dinner table—if only the subject were not such a horrific, life-altering tragedy.

Soon after Jack died, they told me, Meryn noticed on her way to work that there were both Ukrainian and Russian Orthodox churches near their home in Lidcombe, a suburb in western Sydney. This was before the O’Briens had any inkling of the full story of their son’s death—the Buk missile launcher and the 53rd Anti-Aircraft Missile Brigade, let alone the disinformation efforts of Russian troll farms. Meryn approached both churches, hoping to gain a better understanding of the distant geopolitical conflict that had claimed the life of their son.

They received greatly differing descriptions of the relationship between the neighboring countries, Jon told me. The Russians typically presented a narrative that focused on the bond between the two peoples. The Ukrainians they spoke with, by contrast, recounted a “long history of conflict and bullying and oppression from Russia from their perspective,” Jon said. The words recalled a post I’d noticed earlier on the O’Briens’ website. Despite their own memories of atrocities inflicted on the Ukrainian people, Jon said, the people he and Meryn spoke with showed great compassion and concern. “They were so sorry,” he told me. “They felt regretful that this had happened to us.”

To mark this year’s anniversary, Jon and Meryn traveled to Canberra, the Australian capital, to take part in a demonstration outside the Russian embassy there. In what was part memorial, part protest, the participants lined an area across the street from the embassy with empty chairs to represent the 298 people who’d been on Flight MH17. They also brought stuffed animals to the memorial to signify the children who were “killed,” Meryn said, before quickly correcting herself—“murdered.”

The MH17 commemorative group was joined by Ukrainians, including newly arrived refugees, and others who had held their own daily protests there since the invasion. No embassy officials emerged—none ever do, they said—so Jon slid through the fence a letter that he’d intended to deliver. (It was gone the next morning, he said.)

One of the most maddening and mind-bending aspects of their son’s death has been the disinformation about the crash constantly peddled by Moscow and amplified by a throng of conspiracy theorists and apologists for autocrats. The Russian ambassador responded to a letter Jon wrote, he told me, which relied on familiar talking points that the plane had been brought down not by a Russian missile, as numerous investigations have concluded, but by a bomb on board or a Ukrainian fighter jet.

“This is not accidental. This is not people groping for an explanation,” Jon told me. “This is state policy. This is systematic denial and disinformation.” For relatives of the victims, he said, this is “another injury … that is just wearing and draining and offensive.” The effect is so disorienting and demoralizing that at one point, Meryn said, Jon began to question himself and what had happened. They have now accepted that “our reality and [the Russian government’s] reality are not going to meet,” Meryn said.

This deliberate, state-sanctioned deception has helped galvanize the Netherlands into action, Marieke de Hoon, an assistant professor of international criminal law at the University of Amsterdam, told me by email. Aviation disasters don’t usually lead to court cases, de Hoon explained, because they get settled between parties who agree on a compensation scheme (sometimes accompanied by an admission of responsibility).

Moscow’s position, which has gone far beyond denial of involvement to manufacturing counternarratives, has “generated a situation for the Netherlands,” de Hoon told me, such “that it would either have to blink and let Russia get away with that level of bullying and deception or instead to take up an immensely complicated task of trying to go through legal procedures to get convictions.”

The criminal trial in the Netherlands originally began in March 2020. The three Russian men—Igor Girkin, Sergei Dubinsky, and Oleg Pulatov—and one Ukrainian, Leonid Kharchenko, are facing 298 counts of murder. The case file is enormous, consisting of some 65,000 pages of documents, as well as hours of audio and videotapes. These include conversations between two of the men in which they discuss shooting down what they initially thought was a Ukrainian warplane. Only Pulatov has legal representation. He asked to be acquitted as the trial was closing, in June. Dutch prosecutors are seeking life sentences for the four. The court will next month announce the date for its judgment, which is expected to be toward the end of the year. Even if convicted, none of the four is likely ever to serve prison time because Russia, where they are believed to be residing, will not agree to extradite them.

The O’Briens attended the opening of the trial in person. Meryn has also watched portions on a livestream provided by the court. Jon said he found it beyond admirable—“staggering,” in fact—that “the Dutch people, through their taxes, are paying for the defense of one of the people being accused of being complicit in the deaths of 200 of their citizens.” It showed, he said, “how serious the commitment to truth is. And contrast that to the crap on the other side.”

Higgins, the Bellingcat founder, hopes that the verdict will mark an important break with the impunity Russia has generally enjoyed for its actions, which has served only to embolden Putin. “They get away with it. There are no real consequences for their actions, and what is happening today is a direct result of that lack of consequences,” he told me. “It took a full-scale invasion of a European country for there to be actual consequences.”

For the O’Briens, the court ruling will help, they hope, crystallize the truth and cut through the disinformation about what happened to Flight MH17 and their son. They are under no illusions that the handful of men on trial represents anything close to the full docket of those who are culpable. “There are a whole heap of people above these four that are responsible and accountable for the murder of those 298 people,” Jon told me. “And, now we know, the deaths of thousands of people in Ukraine.”