Audio: Thomas McGuane reads.

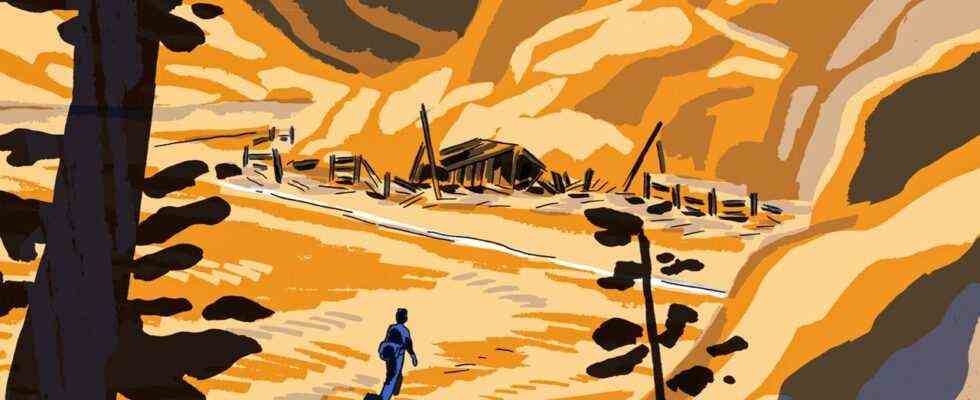

Cary was out of likely places to cross. The five-strand ranch fence was on the county line, ran south, and would guide him to the canyon and the wild grasslands beyond. He could go all the way to Coal Mine Rim and a view dropping into the Boulder Valley. Due south he could see the national forest, the bare stones and burned tree stubs from the last big forest fire. After the fire, a priest who loved to hike had found nineteenth-century wolf traps chained to trees. The flames and smoke had towered forty thousand feet into the air, a firestorm containing its own weather, lightning aloft, smoke that could be seen on satellite in Wisconsin. The foreground was grassland but it had been heavily grazed. In the middle of this expanse, a stockade, where sheep were gathered at night to protect them from bears and coyotes, had collapsed. The homestead where Cary’s dad had grown up and where Cary himself had spent his earliest years was in a narrow canyon perpendicular to the prevailing winds, barely far enough below the snow line to be habitable. Around his waist, in a hastily purchased Walmart fanny pack, he carried his father’s ashes in the plastic urn issued by the funeral home, along with the cremation certificate that the airline required.

Once, these prairies had been full of life and hope. The signs were everywhere: abandoned homes, disused windmills, straggling remnants of apple orchards, the dry ditches of hand-dug irrigation projects, a cracked school bell, the piston from an old sheep-shearing engine. Where had everyone gone? It was a melancholy picture, but maybe it shouldn’t have been. Perhaps everyone had gone on to better things. Cary knew enough of the local families to know that things weren’t so bad; some had got decidedly more comfortable, while claiming glory from the struggles of their forebears. Where the first foothills broke toward the Yellowstone, a big new house had gone up. It had the quality of being in motion, as though it were headed somewhere. It had displaced a hired man’s shack, a windmill, a cattle scale, and had substituted hydrangeas and lawn.

After his father died, Cary had flown to Tampa and then driven north to the retirement community where his dad had ended his days in a condominium that had grown lonely in his widowhood. Cary sped through the Bible Belt, where “we the people” were urged to impeach Barack Obama. The billboards along this troubling highway offered a peculiar array of enticements: needlepoint prayers, alligator skulls, gravity deer feeders, pecan rolls, toffee. “All-nude bar with showers.” “Vasectomy reversal.” “Sinkhole remediation.” “Laser Lipo: Say goodbye to muffin tops and love handles!” “It’s a Small World. I know. I made it.—The Lord.” A car displayed a sign that said “I work to cruise” and a cartoon ocean liner running the full length of the rear window, with an out-of-scale sea captain waving from its bridge.

We the people.

Cary thought that his old man had had a pretty great American life. He’d lived on the homestead through grade school, attended a small Lutheran college in the Dakotas, flown a Douglas A-4 Skyhawk named Tumblin’ Dice in Vietnam, worked as an oil geologist all over the world, outlived his wife and their mostly happy marriage by less than a year, spent only ten days in hospice care, watching his songbird feeders and reading the Wall Street Journal while metastatic prostate cancer destroyed his bones. “Can’t rip and run like I used to,” he’d warned Cary on the phone. He’d died with his old cat, Faith, in his lap. He’d once said to Cary, “In real psychological terms, your life is half over at ten.” For him, ten had meant those homestead years, wolf traps in the barn, his dog, Chink, a .22 rifle, bum lambs to nurture, his uneducated parents, who spoke to him in a rural English he remembered with wry wonder: as an adult, he’d still sometimes referred to business disputes as “defugalties” or spoken of people being “in Dutch.” The old pilot had observed himself in his hospice bed, chuckled, and said, “First a rooster, then a feather duster.” His doctor had given him a self-administered morphine pump and shown him how to use it sparingly or on another setting: “If you put it there, you’ll go to sleep and you won’t wake up.” His warrior buddies at the retirement community had held a small service, with tequila shots and music on a homemade CD that finished with a loop of “The Letter,” which played until a carrier mechanic who’d serviced Tumblin’ Dice replaced it with “Taps.”

Cary didn’t spend long at the condo—long enough to meet the Realtor, long enough to pick up a few things, including photographs of himself up to sixteen. What an unattractive child I was, he thought. The rest were shots of aircraft, pilots, crews, flight decks. Judging by the framed pictures, his mother was forever twenty-two. He took his father’s Air Medal, which was missing the ribbon but had fascinated him as a child, with its angry eagle clasping lightning bolts. “That bird,” he’d called it. He put it in his pocket and patted the pocket. He took the black-and-white photograph of his great-grandfather’s corral, with the loading chute and the calf shed, and the distant log house. “We lived in the corral,” his father had joked. He’d told Cary plainly that he had grown up poor. He remembered his grandfather, who’d started the ranch, prying the dimes off his spurs to buy tobacco, sticking cotton in the screens to keep the flies out. The old fellow had spanked him only once, and it was for deliberately running over a chicken with a wheelbarrow. Cary’s great-grandfather was a cowboy, who moved through cattle like smoke, who could sew up a prolapsed cow in the dark with shoelaces and hog rings. His only child, Cary’s grandfather, had detested the place, had done almost no work, and had lost everything but the homestead to an insurance company. A tinkerer and a handyman, a tiny man with a red nose in a tilted ball cap, he ran the projector at the movie theatre in town. When Cary’s father was home from the war, he took him to see his grandfather up in the booth; Cary remembered the old man pulling the carbon rods out of the projector to light his cigarettes. An unpleasant geezer, he’d peered at Cary as though he couldn’t quite put his finger on the connection between them, and said, “Well, well, well.” Years later, his father said, as though shooing something away, “Dad was a failure, always flying off the handle. My mother ran away during the war to build ships. Never seen again, never in touch, had me and vamoosed. Dad used to look at me and talk to himself: ‘Can’t figger out why the little sumbitch is swarthy.’ Went broke trying to sell pressure cookers. Once left a town in Idaho in disguise. He told me it was plumb hard to be born on unlucky land.” In the projection booth, Cary’s grandfather said that he was busy and told Cary to get lost. Cary’s father stayed behind, and Cary heard him say, “Lord have mercy, Daddy. You’d give shit a bad name.”

Cary’s other grandfather, the glowing parent of Cary’s mother, a former Miss Arkansas—or a runner-up, depending on who was telling the story—was a lunatic entrepreneur named J. Lonn Griggs, who’d made a fortune selling swamp coolers, reconditioned tractors, and vitamins. Grandpa Griggs had long white hair like a preacher’s, and, according to Cary’s father, was as crooked as the back leg of a dog. He adored Cary and Cary adored him back.

To reach the canyon, it was necessary for Cary to circumvent a property vehemently marked with “No Trespassing” signs, a house with a circular driveway that looked like a West Coast taco shop. A figure appeared on the lawn as he passed, a glint of binoculars, and presently an A.T.V. dashed down toward him. Cary pressed on, his fanny pack and its contents jabbing the small of his back, but encountered more signs. It was hard to say how far this property extended.

The rider of the A.T.V. stopped at the line of sagebrush that Cary had hoped would make him less conspicuous, dismounted, and hung his binoculars on the handlebar. He was there, it was clear, to confront Cary, and though he seemed in no hurry, Cary sensed that it might not be appropriate to go on his way. He waited as the man approached, a tall, white-haired fellow in khaki pants and a blue checked shirt, with a fierce smile on his face. The smile suggested to Cary that the man was about to introduce himself, but instead he heard in bell-like tones, as he drew closer, “You’re trespassing.”

“I’m so sorry but I’m on my way to visit my grandfather’s homestead, just”—Cary pointed—“at the mouth of that big coulee.”

Without changing his smile, the man said, “There’s nothing there anymore. And I own it.”

“Ah,” Cary said, and continued on his way.

He heard the man call out, “Do you know our sheriff? He was born here.”

“So was I,” Cary said.

It was a beautiful day for a walk, and his mind was filled with family memories and memories of the girl he’d married and to whom he should have stayed married. His father had been displeased with him for his part in the breakup, a painful thought just now. Once, he’d sat with his parents in their kitchen as they talked without wondering if he should be listening. Often they were tipsy, with the mellow look in their eyes that he would eventually dread. “The cop,” his father mused, “claimed I had wandered across the yellow line four times. I told him I was distracted because I was eating. The cop says, ‘I don’t see no food.’ I said, ‘That’s because I ate it.’ The cop says, ‘Just go home, you’re drunk.’ ” They giggled complacently. Cary remembered how peacefully they’d enjoyed the story; they had a kind of companionship, he supposed, one that began when his father had the uncertain future of a fighter pilot and his mother was a pilot’s wife. Years later, when these two handsome people had wearied, one of those funny stories had turned into a quarrel and his mother had dropped her head to the counter and wept that she’d been Miss Arkansas. “The world was my oyster!” By then, they no longer shared these moments with Cary, who, twirling a cap pistol, heard this from the top of the stairs. Then they were in love again, both love and rage fuelled by alcohol. They found it irresistible. By late in the day, you could see how tiresome life had become without it. Over time, his father managed better; she went crazy, with raccoon eyes and strawlike orange hair. On nights when she “did her number”—a frightening performance of laments and despair—his father turned to him to explain, “The situation is hopeless but not serious.” Soon she was reminiscing about being the “lady love” of various Arkansas landowning boyfriends. Cary caught his father’s eye. His father smothered a smile, while Cary fought back a dazed sensation. If it was funny, he couldn’t bring himself to laugh.

When Cary was twelve, his father asked him to record her. He thought it would help if she, sober, could hear how she sounded. “I was wearing a wire!” Cary’s former wife, a normal person raised by normal people, was fascinated by the ingenuity of dysfunctional families. “Are you serious? Record your own mother?” His parents increasingly relied on electricity—cardioversion for his father’s unreliable heart, shock therapy for his mother’s brain, a wire for self-awareness. “Had to hook ’em up,” Cary explained to his therapist. He had little to say to, or to hear from, the therapist, Dr. Something-or-Other. Cary was there only to reduce his meds—not to hear, in so many words, that there was more to life than getting even with one’s progenitors. Why pick on high-functioning basket cases?

You might not know the homestead had ever existed were it not for the fragments of foundation, some persistent hollyhocks, a caved-in stock tank, and a bit of still diverted creek. When a homesteader failed, the neighbors swept in to take anything they could use, even the log walls. Here they had left a tub and a wringer and the lid of a washing machine. Cary knelt to pick it up and saw the thick gray-green mottled curl of a rattlesnake. He lowered the lid carefully, shutting off the sound of the rattle. He dusted his hands vigorously, raised his eyebrows, and exhaled.

A hand-dug well was dry, the debris of its walls filling it. Some of the walls still stood, and here Cary dropped the cannister with his father’s ashes and the Vietnam Air Medal, pushing in the remains of the wall to cover them. His father had asked him to do this: “If you have nothing better to do.” He thought of putting a memento of the place in his now collapsed fanny pack, but nothing caught his eye. Honestly, nothing about the scene was familiar at all.

The landowner was at the fence as he passed. “I told you there wasn’t anything left.”

“I wanted to see it.”

“See what?”

Cary winced. “Not much. Just the lid of an old washing machine. I long ago hid five perfect arrowheads underneath it. They were still there! I didn’t disturb them.”

Cary kept walking as he heard the A.T.V. head toward the homestead. When he got to the county road, his rental car was missing. “What’ll they think of next?” he mused. It made for a splendid afternoon walk in open country past the prairie foothills, a snowy saw edge far away. Birds dusted along the road, field sparrows, buntings; meadowlarks swayed atop mullein stalks and sang. His father had walked this road to his one-room school, where bear cubs had tumbled from the crab apples, and girls had ridden ornery horses with lunch pails tied to saddle horns. The library had consisted of National Geographics, in which eighth-grade boys had discovered the breasts of African women until farmers cut out the pages.