The new three-part documentary series “Victoria’s Secret: Angels and Demons,” on Hulu, opens with a backstage scene. There are only a few minutes left before the lingerie company’s annual fashion show is slated to begin, and, as scads of photographers mill about, the supermodels set to walk the runway grin and pout for the cameras. With their cascading curls and sculpted cheekbones, their bodies clad in skimpy underthings, these so-called Angels—the company’s name for its brand ambassadors—embody a fantasy world in shades of pink and white and tan. And yet the scene also captures the instances in which this dizzying illusion momentarily breaks: Kendall Jenner rolling her eyes after being asked to pose for what is surely the umpteenth half-naked iPhone portrait; Bella Hadid’s face growing slack once a photographer is done capturing her; the too-snug panties riding awkwardly up the posteriors of two models as they pose on a table, like a pair of Ferraris on a car show’s platform. “We’re professional girls. We know how to act when the camera is on,” Tyra Banks, the supermodel and onetime Victoria’s Secret Angel, explains brightly in an archival interview, later in the documentary. But what happens when the camera is off?

This is one question that “Angels and Demons,” directed by Matt Tyrnauer, is interested in answering. The series examines the often unpretty behind-the-scenes story of Victoria’s Secret, which, in the hands of its parent company’s C.E.O., Leslie Wexner—an enigmatic billionaire with close ties to the late convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein—grew from a modest business in the early nineteen-eighties to a mammoth corporation, and one of the most prominent mall brands of the turn of the millennium, before seeing its fortunes fall in the sociocultural reckoning of the past half decade. But beyond the exploration of Wexner’s Epstein links and the real-life fissures in the fantasy world Victoria’s Secret built—the sexual-harassment claims, the pernicious body-image messaging, the lack of diverse representation—Tyrnauer’s documentary is especially worth watching for the light it shines on the dreams the company sold, which were powerful enough to shape our collective imagination of what a woman can and should be. “Fantasy is more real than reality to Americans, generation after generation,” Tyrnauer told me, when I met him recently in Los Angeles. “For me, that’s a constant theme.”

Tyrnauer grew up in L.A., and, after attending college at Wesleyan, moved to New York, where, in the early nineteen-nineties, he began to write for the Condé Nast magazine Vanity Fair under the editor-in-chief Graydon Carter. Most of his reporting, Tyrnauer said, focussed on the “evil and glamour of evil” that typified the lives of the rich and powerful. (“At Vanity Fair, it was part of the job description,” he said with a laugh.) Tyrnauer became a kind of participant-observer: although he kept the subjects he wrote about at arm’s length, he was fascinated by the place they inhabited in society. “I never wanted to be of it, but I felt it was really important, because it’s what made the world go round,” he said. In 2009, he transitioned into filmmaking, releasing a documentary called “Valentino: The Last Emperor,” based on a Vanity Fair story he wrote about the baroque and extravagant world of the Italian designer. Since then, Tyrnauer has turned his focus stateside, exploring figures who, in their hunger for domination, success, and pleasure, embody what he sees as “the American psyche in the late twentieth century.” These include the McCarthy and Trump henchman Roy Cohn (“Where’s My Roy Cohn?”); the club owners Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager (“Studio 54”); and the Presidential spouses Ronald and Nancy Reagan (“The Reagans”). “There’s this adage that directors make the same movie again and again,” Tyrnauer told me. “And the common theme in all of mine is, generally, power.”

It’s no surprise, then, that the story of Wexner and Victoria’s Secret piqued Tyrnauer’s interest. In the mid-sixties, Wexner, who was born in 1937 to a family of not particularly thriving Ohio garmentos, opened his first apparel store, The Limited, and quickly revealed himself to be an extremely ambitious businessman. He was “a Jewish kid, obviously very bright, with a tremendous amount of drive, in this very Waspy, anti-Semitic, John Birch Society city,” Tyrnauer said. “Outsiders often have their finger on the pulse. They know the tropes and ingredients of the inside track.” The Limited eventually became L Brands, a multibillion-dollar company that came to include, in the course of the eighties and nineties, popular retailers such as Victoria’s Secret, Abercrombie & Fitch, and Bed Bath & Beyond.

For Wexner, helming the L Brands behemoth meant not just amassing legendary wealth but also having a hand in defining what late-twentieth-century American identity looked like. On the outskirts of Columbus, he developed New Albany into a sterile, upper-class, goyish manqué community where even the size of newly planted trees was regulated: a Ralph Laurenesque utopia in which he owned the largest estate. Among his corporate properties, Abercrombie & Fitch (a label whose own troubling backstory was explored recently in Alison Klayman’s Netflix documentary, “White Hot”) was meant to outline the figure of the hunky, white, football-playing frat boy—an image that, thanks to the photographer Bruce Weber’s nudes-in-nature ad campaigns, thrummed with homoerotic undercurrents. Victoria’s Secret, meanwhile, was meant for the woman who that kind of guy supposedly wanted to marry, or, at the very least, jerk off to.

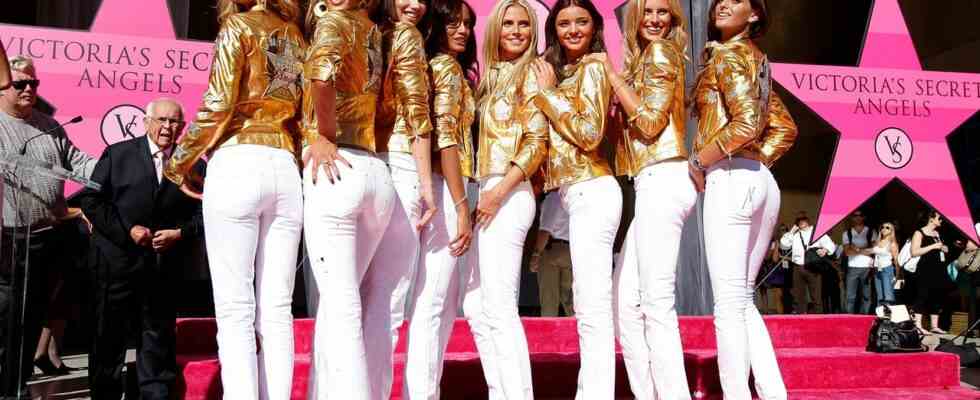

“Angels and Demons” skillfully plots out the path that Victoria’s Secret took, under Wexner and his right-hand man, L Brands’ C.M.O. Ed Razek, to invent and brand this dream woman. Early on, she was “Victoria Stewart-White,” a genteel Englishwoman with a saucy continental side. (One of the series’ coups is its inclusion of some of the company’s internal branding videos, which need to be watched to be believed: “Mother was passionate, a fiery Frenchwoman with a quick temper and a healthy disrespect for the English and their stodgy ways,” “Victoria” narrates in a faint British accent, in a clip meant to tell the figure’s origin story. “She used to tease Father about everything.”) As the new millennium neared, the brand’s ideal woman became raunchier, and the “Angels” were born: supermodels such as Stephanie Seymour, Heidi Klum, and Gisele Bündchen, bombshells trussed up in ever-tinier bits of lace and satin and mesh, strutting down the runway at the annual, spectacularly popular Victoria’s Secret show, and in high-concept, high-budget commercials directed by the likes of Michael Bay.

Victoria’s Secret, Tyrnauer told me, became about “using sex to sell things you don’t need.” This had a price. As a former employee of the company recounts in the series, Wexner and Razek rejected anything that had to do with women’s real-life necessities: “nothing to do with maternity, nothing to do with shapewear, nothing to do with comfort . . . It was just, like, boom, this woman shot out of a cannon and born perfect and impossible to become.” Even the Angels, God bless them, had a difficult time keeping up. The images of some of the models, an employee recalls, were retouched to within an inch of their lives.

In the mid-two-thousands, Victoria’s Secret expanded into the teen market with the diffusion brand Pink, making sexiness a covetable goal for an even younger customer. “The topic A of every podcast is the impact Instagram has on women and young girls, and I think you can see the 1.0 of that with the mall, and with these marketing machines that deranged generations of Americans,” Tyrnauer told me. “Victoria’s Secret is a case study of that.” As we spoke, I recalled shopping at the chain for the first time as a high schooler in the nineties. It would be some years before the brand’s circa-two-thousands “What Is Sexy?” campaign would début (the answer to that question implicit in the soft-core images of pushup-bra-wearing Angels that adjoined it), but I already understood that the company was selling me a very particular idea of eroticized femininity. Purchasing a purple lace bra, I felt a certain amount of pride—I was a woman now!—but also some concern. Was I, at fifteen, ready to take on the work of seduction that the brand promoted? Conversely, would I ever remotely resemble the models on the store’s walls? The boons and burdens of millennial American womanhood stretched before me, as if already foretold.

“Angels and Demons” touches on these questions from another angle by exploring the links between Wexner and Epstein. In the wake of Epstein’s 2019 arrest and his subsequent jail-cell suicide, questions arose about the close relationship between him and Wexner, which began in the eighties, when the Ohio mogul attempted to make his way into New York society with the suave, connected Epstein as his plug. Wexner effectively made Epstein his money manager, and also gave him full power of attorney over his assets—a move so rare that the business journalist Sarah Ellison, interviewed in the series, says that she hasn’t seen anything like it “in all of her years of reporting.”

The documentary carefully traces the relationship between Epstein and Wexner: Epstein’s posing as a Victoria’s Secret scout and molesting a model in a Santa Monica hotel room in the late nineties (she filed a police report at the time); Epstein’s obtaining of Wexner’s palatial town house on the Upper East Side and a former The Limited corporate plane, later known as his “Lolita Express,” as well as a guest house on Wexner’s Columbus estate, where Epstein and his partner, Ghislaine Maxwell, sexually assaulted a young painter, Maria Farmer. There were also the persistent rumors that there was something beyond the collegial and friendly between Wexner, a late-marrying Columbus businessman, and Epstein, who never married at all. (Wexner refused to be interviewed for the documentary, but, through his lawyers, he categorically denied any knowledge of sexual misconduct by Epstein while they were working together, and also denied having had a sexual relationship with him; he maintained, as well, that he severed ties with Epstein in 2007, after the latter’s first arrest on a solicitation charge a year earlier.)

“What was the real relationship between these two men? I don’t know whether we’ll ever know,” Tyrnauer said. But, if Wexner’s exact involvement in Epstein’s affairs remains murky, one thing that does clearly emerge from the series is the parallel between Epstein’s crimes and the cultural landscape that Victoria’s Secret created. As I watched, I was reminded of Trump’s comments to New York magazine, in 2002, in which he called Epstein a “terrific guy” who “likes beautiful women as much as I do, and many of them are on the younger side.” It struck me that this wasn’t just a barely cleaned-up way to present Epstein’s nefarious proclivities but also a straightforward definition of the brand’s modus operandi in its golden era. In their Victoria’s Secret finery, the Angels were beautiful and on the younger side. Be like them—be sexy—and you might snag yourself a mogul, too.

Of course, the last half decade’s rise of activism in the wake of the #MeToo movement, and the calls for increased representational inclusivity—in terms of body size, race and ethnicity, and gender—have changed the playing field dramatically. More overtly inclusive lingerie companies such as ThirdLove and Rihanna’s Savage X Fenty bit into Victoria’s Secret’s share of the market, and in 2016 sales began to slip. Initial attempts to reverse the trend by presenting Victoria’s Secret’s wares as embodying feminine strength and fierceness seemed like too little too late. (“They thought they could fool a few more people and talk about empowerment,” the journalist Michael Gross says in the series.) And yet Razek’s and Wexner’s retirement in 2018 and 2020, respectively—Razek’s the year before he was accused of sexual harassment, which he denied—signalled a pivot. The annual fashion show was cancelled, and the Angels were retired. In their wake, Victoria’s Secret presented “the collective”: “trailblazing partners” who represent the company’s new values, including the lesbian soccer champ Megan Rapinoe, the plus-size model Paloma Elsesser, and the trans activist and model Valentina Sampaio.

Showcasing diversity rather than presenting customers with the same unattainable ideal is undoubtedly a positive development. (As the former Angel Lyndsey Scott notes in the documentary, “It’s also a smart business move”: recent reports suggest that, for the first time since 2015, Victoria’s Secret sales are up.) And yet the series ends on an ambivalent note. Victoria’s Secret was prompted to change its image, partly thanks to the propulsive power of social media, but its legacy is still with us, particularly in the figure of the influencer. It made me think about a point the documentary doesn’t explicitly dwell on: it may not matter if men such as Wexner and Razek are no longer at the helm, since women can make other women feel like shit just as well as men can. In May, the billionaire reality star Kim Kardashian, who lost sixteen pounds in three weeks to fit into Marilyn Monroe’s gown at the Met Gala, told the New York Times, in an interview promoting her new skincare line, that she just might “eat poop every single day” if you promised that it would make her look younger. It was a sentiment straight out of the aughts Victoria’s Secret playbook. ♦