This article is part of the launch of extended tennis coverage on The Athletic, which will go beyond the baseline to bring you the biggest stories on and off the court. To follow the tennis vertical, click here.

Last month at the Madrid Open, Coco Gauff was warming up on the least desirable practice courts when she saw some male players — without small numbers next to their names — on the much better courts.

Gauff is familiar with the misogynist history of the tournament. She partnered with compatriot Jessica Pegula against Victoria Azarenka and Beatriz Haddad Maia in the women’s doubles final in 2023, after Azarenka and other players commented on unfair scheduling and the size disparity of birthday cakes for Carlos Alcaraz and Aryna Sabalenka.

Officials refused to let the foursome speak after the match.

Gauff said she had seen progress this year. But she couldn’t help but notice the weirdness: she, a Grand Slam champion and the world No 3, was warming up at an event just one rung below the U.S. Open on “really bad” courts.

“When you look out on the practice court and you see guys who are ranked 30 or 40 spots lower than you on the court, you’re like ‘OK, what happened?’” she said a few days later.

Gauff during the Madrid Open (Oscar del Pozo/AFP via Getty Images)

Maybe that doesn’t sound like a big deal. She played her match on the top court, in a desirable time slot. There are plenty of benefits that Gauff and a handful of other women at the top of tennis enjoy, including prize money and endorsements that can reach into the tens of millions of dollars.

Still, to exist as a female tennis player in 2024 is to endure what can feel like endless slights: the micro-aggressions baked in; the structural inequality foundational to a sport run mostly by men; stark set-piece examples of inequality that can be hard to comprehend and harder to endure, for their magnitude, their reasoning, or more commonly both.

“I get a little bit frustrated here because I feel some tournaments in Europe can fancy men more than women,” Ons Jabeur, the two-time Wimbledon finalist from Tunisia, told The Athletic in Madrid.

“I see that especially on social media, more posts about the men, more this more that and for me it’s really frustrating because we play really well. And it’s such, you know, an amazing sport for women. So I wish we can be more seen,” she said.

“I think we deserve better.”

It’s not just Europe.

Jabeur, 29, just finished playing the Italian Open, where the women competed for a prize pool of $5.5 million. The men’s equivalent was $8.5 million.

In August, the men and women arrive at the Western & Southern Open in Mason, Ohio. The men play for $7.9 million; the women for $6.8 million, even though the tournament owner, Ben Navarro, has a daughter, Emma, who plays on the WTA Tour.

A tournament spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

The knee-jerk reaction is that women don’t bring in as much money as the men, and if they did they wouldn’t be second-class citizens. Yet consider a counter-narrative: during the 55-year history of the sport’s modern era, if women had received the same exposure and investment as men, and didn’t have to confront countless barriers and aggressions, maybe they would be bringing in the same amount of money.

Consider that more generally, the WTA Tour’s most lucrative route to additional funding centers on being in lockstep with the ATP Tour men, over letting Saudi Arabia, a country where women do not have equal rights, pump money into tennis.

How else do elite women get the short end of the racket handle in the sport to which they dedicate their lives?

Let us count — just some of — the ways.

GO DEEPER

Tennis’ top women say the sport is broken. This is why

Ever the bridesmaid

It’s the final weekend of a Grand Slam tournament. The women’s singles final takes place on the Saturday. The climax arrives 24 hours later, with the men’s final.

It’s been that way basically forever. There’s an implicit message that everyone in tennis, from the little girl who just started taking lessons to the world No 1, receives.

Tournament officials often say it has to be this way. The men play best-of-five sets in the Grand Slams; the women play best-of-three. (We’ll get to that. We have thoughts.)

Whoever plays the final on Saturday has to have one day during the tournament where two players compete on consecutive days, between the second day of quarter-finals and the semi-finals. Since the men play longer matches, it wouldn’t be fair for their semi-finalists to have to play on consecutive days, would it?

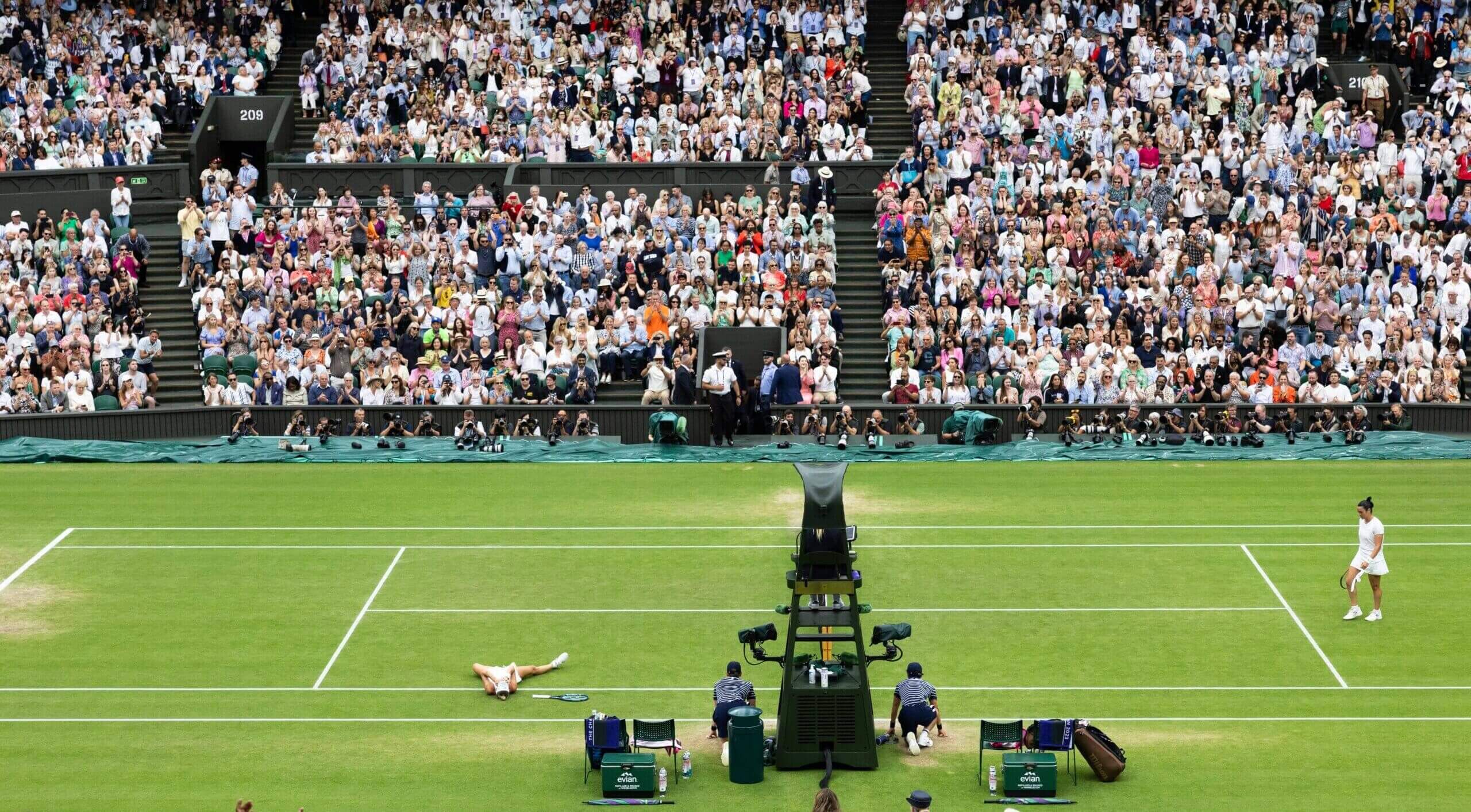

Marketa Vondrousova collapses after winning Wimbledon 2023 against Ons Jabeur (Tim Clayton/Corbis via Getty Images)

Perhaps not. The French and Australian Opens now stretch their first round over three days, and the other Grand Slams could follow suit. Surely there is a permutation that allows the men and women who have reached the late stages of the peak of their sport equal rest?

Of course, there are also television contracts that exist — television contracts that get renegotiated all the time. If there is a will, perhaps there is a way.

If there is a will.

Darren Pearce, chief spokesperson for Tennis Australia, said they have looked at a swap and will continue to do so. They moved the women’s final to Saturday night in 2009 to maximize domestic exposure, but they have to consider time zones and international exposure as well. Pearce cited Australian Ash Barty’s win in 2022 as an example of the Saturday offering “so much more coverage and exposure in Australia.”

The U.S. Open has looked at swapping the two finals “in an effort to optimize viewership and interest,” said Brendan McIntire, a USTA spokesperson.

Last week (Wednesday May 15), ESPN announced that its free-to-air broadcaster, ABC, will show the U.S. Open men’s final, though the women’s final the day before will remain on the pay channel, ESPN, because ABC has contractual commitments to college football that Saturday.

The U.S. women’s final has outperformed the men’s final four of the past five years in television viewership, and the men’s final competes with the opening weekend of the NFL. In this case, the second-class spot may be a blessing.

A Wimbledon spokesperson said the current set-up offers “the right balance.”

What about the big mixed events where both the women and the men play best-of-three sets?

Indian Wells has a finals Sunday on which both the women and the men play — guess who plays first? Cincinnati will hold the finals on the same day this year, and we’ll see who goes first. Miami, Madrid and Rome have the women play Saturday, the men Sunday.

“I don’t really think that it’s just a question of money, but also respect,” Jabeur said. “It’s small details that make the difference.”

It happens in a macro way, too. The WTA Tour Finals take place the week before the ATP Tour Finals. The Billie Jean King Cup wraps up before the Davis Cup, although there will be overlap from this year.

Swiatek triumphed in this year’s Indian Wells (Robert Prange/Getty Images)

Next year, Great Britain’s Lawn Tennis Association will host a women’s WTA 500 at the Queen’s Club in London. It will begin immediately after the French Open, the week before the men take the stage at Queen’s, and in the build-up the focus has been not on the benefits of a women’s tournament at such a prestigious event, but whether or not the ATP is happy that the grass will be pristine enough for male feet after a week of tennis.

There will not be equal prize money.

GO DEEPER

What’s the one thing you would change about tennis?

Games, sets, and matches

Jessica Pegula, the world No 5 and a member of the WTA Player Council made it very clear at the French Open in 2022.

“I don’t want to play three out of five,” Pegula said.

She’s hardly the only one. It’s a slog, with matches that can stretch beyond five hours, and then you have to do it all over again two days later. There is not a throng of women’s players clamoring for best-of-five tennis at the Grand Slams.

It’s still the third rail of equality in tennis.

Aryna Sabalena en route to victory at this year’s Australian Open (Andy Cheung/Getty Images)

Best-of-five sets only exists at the Grand Slams, where women and men compete for the same prize money — and a lot of folks complain that it’s equal pay for less work every time it comes up. It’s a prime example of another uneven dynamic, where women have to account for every possible bad-faith accusation that could emerge before opening their mouths on the biggest issues in their sport.

Duration isn’t the only element of work. Best-of-three requires immediate competitiveness, with little time for recovery. It’s not Swiatek’s fault that she is so good at plowing through the competition, and it’s no player’s fault that the best players in the men’s game might drop two sets to lesser opponents and have to claw back three.

It’s also not any WTA player’s fault that tennis audiences sometimes dismiss the variety of styles in the women’s game as “boring” — though they’re probably talking without watching. Anyone who has watched a WTA match this year, especially between Swiatek, Sabalenka, Gauff, and Rybakina would have to agree with the Pole’s comments after her Madrid final against Sabalenka.

“Who’s gonna say now that women‘s tennis is boring?”

GO DEEPER

Men’s grand-slam matches are 25% longer than in 1999. Does something need to change?

Stardom also fluctuates. When Wimbledon, and the French, U.S. and Australian Opens sell tickets, sponsorships and media rights, they mostly don’t sell separately for the men’s tournament and the women’s tournament. There were plenty of days and nights when Serena Williams was the featured match in New York and elsewhere, and a couple of guys were the undercard or the afterthought. In Rome this month, where men and women play best-of-three, the WTA semi-finals featured the top three players on tour and the best form player of 2024 in Danielle Collins, with the final again between world No 1 Swiatek and world No 2 Sabalenka.

The men’s semi-finalists had an average ranking of 19, with one of the finalists, Alexander Zverev, about to defend himself in a domestic abuse hearing while continuing to play. Some of that is to do with the caprices of injury and form — but they are intrinsic parts of tennis, and they don’t change the fact that the WTA Tour appears to be locking in to a generational rivalry while the ATP Tour is in relative flux.

If a similar dynamic emerges at Roland Garros, is the men’s event still qualitatively better because of two more sets?

Billie Jean King, the trailblazing Grand Slam champion and founding figurehead of the WTA Tour, is adamant: as long as there are different formats, there will be inequality.

Hang around with her even a little bit, and three phrases keep coming up.

“Same format.” “Equal content.” “Equal exposure.”

To King, if a women’s match only lasts 60 percent as long as a men’s match, then they will receive 60 percent of the television exposure as the men, and spend 60 percent of the time on the biggest courts in the biggest tournaments.

Sue Barker with Serena Williams on the BBC in 2016 (Visionhaus/Corbis via Getty Images)

That math practically guarantees that women are less well-known and attract less money. There are exceptions — Williams, Maria Sharapova, Naomi Osaka, Emma Raducanu, Coco Gauff — but the numbers are hard to overcome. World No 1 Swiatek has recently bagged the huge sponsorships her status deserves, but it’s taken time.

GO DEEPER

Iga Swiatek’s 100 weeks as world No 1: The streak, the slams, the bagels

Tournament directors say having men and women play best-of-five is impossible from a scheduling perspective. Too many too-long matches. Too few courts. And the players don’t want it.

King and others have offered a solution — best-of-three for everyone the first week; best-of-five the second. There’s precedent — 50 years ago at the French Open, the men played best-of-three for the first two rounds. Bjorn Borg and Chris Evert won their first Grand Slam titles, and you might remember that they did pretty well after that. The sun also continued to rise in the east.

The knock-on effects of the current system on scheduling also virtually guarantee more conflict and inequality — sometimes in the name of equality.

As night follows day

Tennis players of a certain age who spent time around private clubs remember times not very long ago when men got first dibs on high-demand slots. Elina Svitolina said that the men (regular players, not tour stars) still get the prime slots at the club near her home in Monte Carlo. Svitolina, top 20 in her sport, formerly a world No 3, had to practice early morning or at dusk.

Three years ago, the French Open started holding a night session with a featured singles match, which now starts at at 8:15 p.m. in the main stadium, Court Philippe Chatrier. The tournament markets it as the match of the day. The U.S. and Australian Open schedule two matches in their night sessions, until the late rounds.

An empty night session on Chatrier between Swiatek and Marta Kostyuk during the Covid-19 pandemic (Christophe Archambault/AFP via Getty Images)

During the first three years, Roland Garros organizers scheduled a total of four women’s matches at night. Amelie Mauresmo, the former women’s world No 1 and tournament director, initially justified the disparity by explaining that men’s tennis is more appealing.

She tried to walk that back but also explained that charging a premium for a session that might finish in an hour is problematic — a knock-on effect of those unequal formats that deprives top women of a primetime audience. Moving a doubles match onto Chatrier after Iga Swiatek blows through an opponent 6-0, 6-1 isn’t seen as viable.

Swiatek made it clear last year that she doesn’t care for playing at night.

“There are players who like the hype and the energy, and maybe the conditions, but for me it’s more comfortable to just have the normal day/night rhythm,” Swiatek said. “I think it’s more healthy for me to play day sessions.”

That was arguably a self-inflicted wound, as were Aryna Sabalenka’s recent comments about preferring men’s tennis. However, this also illustrates another unspoken dynamic: women have to be extra careful not to say anything denigrating about their sport, lest they get criticized for not supporting fellow players, even though a top men’s player saying something about their sport would likely not be considered an existential threat to its repute.

It’s also rare that male players speak up. Andy Murray’s corrections of journalists’ “first…” stats are an exception: the three-time Grand Slam champion has routinely reminded journalists of their forgetting about the Williams sisters, most notably in 2017 when a reporter claimed Sam Querrey was the first American to reach a major semi-final since 2009. Canadian Denis Shapovalov wrote that “I think some people might think of gender equality as mere political correctness” in an essay on the equal pay in the Players’ Tribune in 2023.

Furthermore, it’s well-documented that top men’s players have unspoken preferences, which they often communicate to tournaments, and which tournaments — unspokenly — try to accommodate or nudge around. (They do this some for top women, too). Rafael Nadal has said clay-court tennis should never take place at night, and it goes on.

The clock ticks past 3:12 a.m as Garbine Muguruza defeats Jo Konta in Melbourne in 2019 (Peter Parks/AFP)

The other scheduling inequality also happens at night. No-one, man or woman, wants to play the second late match at the U.S. or Australian Open, with a ridiculous start time.

The men argue that if women are getting equal pay then they should play the late match half the time. OK, but then a men’s match goes five sets in four hours and the women start at 11:30 pm in an empty stadium.

Sometimes scheduling benefits to men happen so fast no one really notices. The Madrid Open experimented with a new doubles format this year, cramming the men’s event mostly into the second half of the second week.

That meant men who weren’t playing the singles got an extra week off. A highly-ranked man who lost early could find a doubles partner, and with him an extra few days of free food, lodging and practice. Nice.

The women’s doubles? It started at the start. They didn’t have that option. Organizers didn’t purposefully set out to deprive them; it just happened, and they had to deal with it.

This attitude extends to matters of inequality in planning and infrastructure off-court, too; anxiety about change doesn’t just extend to the number of sets played or matches scheduled.

Wimbledon only relaxed its all-white dress code after concerns from players about menstruation last year, where the tournament previously required all clothing, including underwear, to be white. At the time, Magda Linette told The Athletic that she has “had a couple of situations at Wimbledon where I felt very uncomfortable,” and welcomed the change, but it had required strident protest at the previous year’s tournament to make it happen.

Top players have become increasingly open about discussing the impact of menstruation on form and performance, with numerous female players talking about PMS’ impact on their game — albeit while coding it as “girl things” in press conferences. China’s Zheng Qinwen saw cramps derail what would have been a famous victory against Iga Swiatek at the French Open in 2022, while Swiatek herself opened up about PMS contributing to her loss to Maria Sakkari of Greece at the same tournament in 2021. “PMS really hit me that day. I’m telling this for every young girl who doesn’t know what’s going on. Don’t worry, it’s normal. Everybody has it,” she said.

Iga Swiatek and Zheng Qinwen at the net in 2022 (Christophe Archambault/AFP via Getty Images)

Women also suffer speculations about general injuries and “illness” that men never have to go through. Combined with the sport’s limited provisions for players that want to have children — there is no maternity pay, even though players that take time out can retain their previous ranking to enter 12 tournaments over a three-year period after giving birth — these changes and the increased visibility, through players like Serena Williams, Naomi Osaka, Caroline Wozniacki, and Elina Svitolina, also reinforce that tennis’ women are playing in a structure built for men.

On the tour, it is ever thus.

GO DEEPER

Wimbledon are relaxing their all-white dress code to ease the stress of women’s periods

(Down) the bottom line

Ultimately, the starkest measure comes in dollars, euros, pounds.

Women and men have received equal prize money at all of the Grand Slam tournaments since 2007. Amid some fanfare, last year the WTA Tour announced that the 500-level tournaments would follow suit, along with that 2027 plan for the 1000-level tournaments one rung below the Grand Slams. But not until 2033, in almost a decade. At the time of the deal, Paula Badosa said, “I don’t know why it’s not equal right now.” Tour officials said new sales and marketing efforts need time to produce more revenue.

The WTA requires top players to participate in every Masters 1000 tournament as part of that deal. World No 4 Elena Rybakina, and Swiatek too, have previously expressed disappointment at the way the WTA communicated these changes. Last year in Rome, Rybakina had to lift her title gone midnight after rain delays. Organizers refused to move the match to Sunday, because of the men’s final. Schedule, audience, money.

Floodlights reflect off the trophy after Rybakina’s win (Filippo Monteforte/AFP via Getty Images)

Tournament organizers have long complained that equal prize money is impossible when WTA media deals are worth about 20 percent of ATP equivalents. Consequently, the WTA contributes far less than the ATP, and the prize money reflects that. That’s how two tournaments in Auckland, New Zealand organized essentially by the same people have the women playing for $262,000 and the men for $660,000.

Last year, male players shared $336million in prize money, including the Grand Slams. Women shared $170million.

Why are those media deals worth so much less? Women often receive second billing in mixed tournaments, play less desirable schedules and don’t get the same television coverage, because their matches are shorter. And then the players get blamed for not being able to bring in as much money. This is how it all coheres, into the ultimate self-fulfilling, blame-the-victim ouroboros that is seemingly impossible to slay.

The coin toss before Vondrousova against Svitolina at Wimbledon (Adrian Dennis/AFP via Getty Images)

Last year, Steve Simon, the chief executive of the WTA Tour, struck a deal with CVC Capital Partners, a private equity firm, which bought 20 percent of a WTA commercial subsidiary for $150 million. The tour has launched a commercial ventures entity aimed at enhancing sales and marketing efforts and improve the visibility of tournaments, part of which is improving streaming and online showings of matches, which are currently limited in comparison to the ATP Tour.

“I would love to go to the hotel and open the TV and see a woman’s tennis match,” Jabeur said midway through the Madrid Open. “I haven’t seen once one tennis match of woman. For me, it’s really frustrating to see that.”

There are more improvements. After a series of disastrous decisions on venues, scheduling, and promotion which came to a nadir in Cancun last year, women will compete for about the same amount of prize money as the men at the season-ending Tour Finals — the WTA’s premier event and a knock-out showcase for the top eight players in the world — for the next three years.

They’ll just have to do so in Saudi Arabia, a country with a long history of human rights abuses, that has jailed women who have run afoul of the country’s leaders by pushing too hard for equality.

Welcome to the new dawn.

(Top photos: Hannah Peters; Julian Finney/Getty Images; Design: John Bradford)