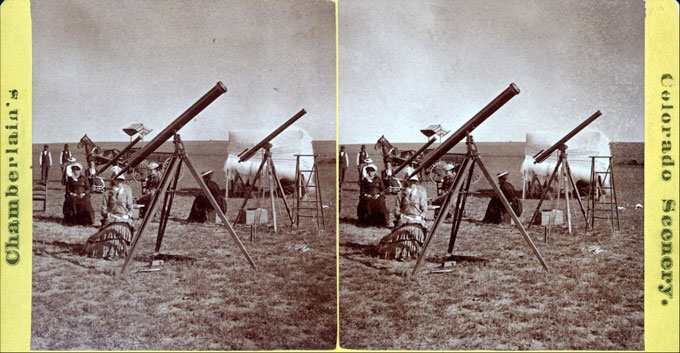

In July 1878, six women scientists, their attendants, a photographer and an artist gathered in Colorado on a panoramic plateau at the foot of the Rocky Mountains. The group had a shared mission: Observe a total solar eclipse. Leading the expedition was celebrated astronomer Maria Mitchell, the first American to discover a comet.

The eclipse captured national attention. The transcontinental railroad, completed the previous decade, made viewing the event accessible to people across the country. Mitchell and her crew — with telescopes and tents in tow — traveled from Boston, through Cincinnati, then Kansas City and on to Denver to watch a phenomenon that would last mere minutes.

But Mitchell knew the journey was worth it. She was one of the most experienced eclipse viewers of her time. During her first eclipse, at age 12, she noted the time out loud so that her father, an amateur astronomer and schoolteacher, could make accurate scientific observations. During her last, in 1885, 54 years later, she again counted the seconds. But this time, she kept time for her students at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, N.Y.

Mitchell’s extensive notes and popular writings about eclipses, especially her rich account of the expedition in 1878, offer insight into the breadth of phenomena visible during a total solar eclipse. These notes still provide guidance for anyone wondering what to watch for during this year’s total solar eclipse on April 8 (SN: 1/4/21).

Maria Mitchell was an astronomy pioneer

Mitchell made the astronomical observation that would bring her international fame and solidify her stature as a scientist on the evening of October 1, 1847. Looking through her telescope from her home in Nantucket, Mass., she spotted an unexpected object. She had just become the first person to observe Comet 1847-VI, later nicknamed “Miss Mitchell’s Comet.”

Thanks to that discovery, she became the first woman elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She also became the first female professional astronomer when Vassar hired her as a professor in 1865.

Mitchell’s legacy as an astronomer and educator remains relevant, says Colette Salyk, an astronomer at Vassar. “She was a very dedicated educator,” Salyk says, ensuring the next generations of women learned about astronomy, including the female scientists she took to Colorado to observe the 1878 eclipse. “That legacy still lasts here at Vassar.”

Astronomers flock to total solar eclipses because certain observations of the sun are possible only during these events. Normally, the sun’s intense rays overwhelm observations of more subtle solar phenomena. But during a total eclipse, when the moon passes between Earth and the sun and blocks the sun’s bright surface, these aspects become observable.

That’s what intrigues Shadia Habbal, a solar physicist at the University of Hawaii’s Institute of Astronomy in Mānoa and a member of the International Astronomical Union’s Working Group on Solar Eclipses. Past eclipses have allowed her to study the composition of the sun’s normally invisible outer atmosphere, the corona. One enduring mystery is why the corona is so much hotter than the sun’s surface (SN: 8/20/17).

But eclipse watching is not just for scientists. “Natural phenomena belong as much to [lay people] as to scientific people,” Mitchell wrote in her notes in 1878. She shared her enthusiasm and knowledge of astronomy with the public by publishing articles in popular magazines like Scientific American.

Habbal agrees that everyone can enjoy an eclipse. She recommends experiencing it with your eyes, not through a camera. In Mitchell’s time, one of the most common ways to preserve the memory of an eclipse was to sketch and write about what you saw.

Some equipment is needed, however. Even glancing at the sun without solar-filtered safety glasses can damage your eyes. In 1857, Mitchell recorded how she transformed a piece of glass broken from a window into protective eye gear: “I smoked it over a piece of candle.”

These days, fortunately, eclipse glasses are readily available.

Once you’ve got your equipment, Mitchell’s notes contain plenty of guidance on what to look out for, from strange shadow effects to the “glory” of the corona.

Look for the “impossible”

On the day of an eclipse, the moon appears to move steadily toward the sun, but that march across the sky is nearly invisible to us. “The moon, when seen in the daytime, looks like a small faint cloud; as it approaches the sun it becomes wholly unseen,” Mitchell wrote in 1878.

It’s challenging to catch the exact moment when the moon starts passing between the sun and the Earth. “Persons who observe an eclipse of the sun always try to do the impossible,” Mitchell noted. “An observer tries to see when this unseen object touches the glowing disc of the sun.”

Historically, this “impossible” observation was an important scientific event. “The exact second by the chronometer when the figure of the moon touches that of the sun is always noted,” Mitchell wrote. At the time, eclipses were still helpful in determining and verifying longitude, which was necessary for creating accurate maps. Noting initial contact was also “a check on our knowledge of the moon’s motions,” Mitchell noted.

To see this first contact, Mitchell advised figuring out where on the sun’s edge the moon will begin to cross the sun, and through protective glasses, watch that point for the moon’s notch.

The good news for casual viewers today is that NASA and other organizations have already done that work. On April 8, the eclipse will begin in the South Pacific Ocean, making landfall at 11:07 a.m. PDT in Mexico, before continuing across the country, the United States and Canada, and then finishing in the evening in Western Europe and the United Kingdom.

After the initial contact, the moon will continue to progress in front of the sun. Mitchell noted that in tracking the moon’s movements, it helps to focus on sunspots — dark blotches on the sun’s surface that form from solar activity (SN: 12/11/20). Because these spots remain fixed during the eclipse, they can serve as points of reference for the moon’s journey. “We watched the movement of the moon’s black disc across the less black spots on the sun’s disc, and we looked for the peculiarities which other observers of partial eclipses had known.” Sunspots can be seen only through solar-filtered glasses.

Look for stars and planets and listen for wildlife

The moment the moon begins to cross the sun, it blocks some sunlight. Progressive darkening ensues for about an hour until maximum blocking is reached. As the sky darkens, observers have a rare opportunity to see planets and stars in the daytime.

The inner planets, Mercury and Venus, are typically visible only just after sunset or just before sunrise, near the horizon. But when the eclipse blocks the sun, they can be seen high in the sky. This year, most of the solar system’s planets will be observable with the naked eye, with Mercury close to the sun. Bright stars will also become visible, and the sun will appear within the constellation Pisces.

Since the stars and planets are so faint, Mitchell suggested that observers try to acclimatize their eyes to get a better look, a recommendation that is still relevant today: “A good observer will remain in the dark for a short time before he makes a delicate observation on a faint star,” she wrote. On eclipse day, try keeping one eye closed or covered for a while before looking at the stars and planets.

As the sky darkens, a sunsetlike effect will span the entire horizon. “What a strange orange light there was in the north-east! what a spectral hue to the whole landscape!” Mitchell noted during the 1878 excursion. “Was it really the same old earth, and not another planet?”

Though the landscape darkens, it is not pitch-black. The pupils of our eyes compensate for the gradual darkening. At most, the sky will appear about as dark as on an overcast day.

The eclipse will also affect the temperature. Because the moon blocks the sun’s radiation, the weather temporarily chills. A variety of animals, including some nocturnal ones, may suddenly become active (SN: 8/12/17). “The neighboring cattle began to low; the birds uttered a painful cry; fireflies twinkled in the foliage,” Mitchell described.

Look for the sights of totality

Although a large swath of North America will have a partial eclipse on April 8, only a small band will see totality, when the moon fully covers the sun. “The moon, although so much smaller than the sun, is so near to us that it usually appears of about the same size… and at the time of a total eclipse seems larger, and more than covers the sun,” Mitchell wrote in 1869.

She traveled to the path of totality frequently during her lifetime to observe phenomena that are visible only during totality.

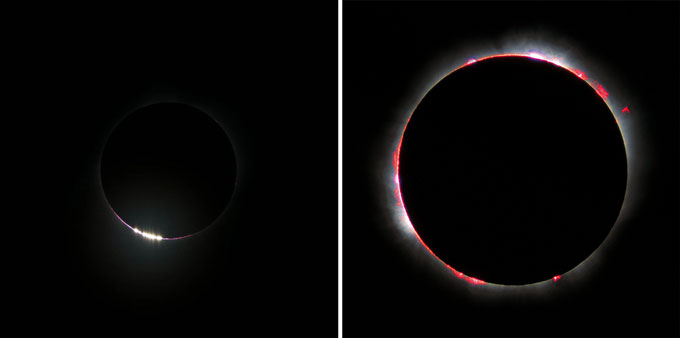

One such effect is Baily’s beads, which appears just before and just after totality (SN: 10/18/23). “As the moon moved on [from its initial contact], the crescent sun became a narrower and narrower golden curve of light, and as it seemed to break up into brilliant lines and points,” Mitchell wrote in 1869. When the moon reaches the apparent edge of the sun, lunar mountains and valleys scatter the remaining sunlight around them, causing the crescent to appear as beads of light.

It is at this moment, when the sun is completely blocked — and only then — that it is safe to remove protective glasses. “Each observer at the telescopes gave a furtive glance at the un-sunlike sun, moved the dark eye-piece from the instrument, replaced it by a more powerful white glass, and prepared to see all that could be seen in two minutes forty seconds [of totality].”

At this point, observers can see the most coveted elements of the total solar eclipse: the sun’s corona and chromosphere.

The corona’s appearance varies from eclipse to eclipse because the sun’s atmosphere is highly dynamic. During an 1869 eclipse, Mitchell noted, “The corona burst out all around the sun, so intensely bright near the sun that the eye could scarcely bear it; extending less dazzlingly bright around the sun for the space of about half the sun’s diameter, and in some directions sending off streamers for millions of miles.”

The corona is normally not visible, Habbal says, because “the disk of the sun is so bright and the corona is a million times dimmer.”

In between the sun’s surface and the corona lies the chromosphere, Habbal says. “Going from the solar surface to the corona, you have the chromosphere, which is very dense and it has a reddish, pinkish hue.” During totality, “you see like a little red rim around the sun.”

Today we know the chromosphere is the cooler, inner atmosphere of the sun, but in Mitchell’s time, it was newly discovered and not well understood. “The corona is mentioned by all the observers of [the 1806 eclipse], but there is no notice of ‘rosy protuberances,’” Mitchell wrote. Those “rosy disturbances” weren’t mentioned by eclipse watchers until 1842, according to Mitchell. She observed the chromosphere in the 1869 eclipse: “The rosy prominences were so many, so brilliant, so fantastic, so weirdly changing, that the eye must follow them.”

Totality lasts only a short time. During this year’s event, it will last a maximum of four minutes and 28 seconds. Mitchell noted that as soon as the sun began to reappear after totality that “all nature rejoiced, and much as we needed more time, we rejoiced with Nature, and felt that we loved the light.”

Don’t forget to look down

There’s more to eclipse viewing than looking up. Many shadow effects seen only during an eclipse are visible by looking down.

Crescent shadows — visible before and after totality, or during a partial eclipse — are the easiest to see. “You start to see all these crescent shadows of light coming through leaves or trees or so on, which is pretty spectacular,” Habbal says. These crescents form from light passing through small openings between leaves or other obstructions. These are essentially pinhole projections showing the shape of the sun as the moon passes in front. The crescents become more pronounced the closer to totality.

Much rarer shadow bands, thought to be caused by turbulence in Earth’s atmosphere, are visible on flat surfaces just minutes before and after totality. “Thin, parallel lines of shadowy waves, they flit silently over the landscape, sometimes faster after totality than before, and indescribably light, airy, and evanescent,” an 1894 astronomy textbook noted.

However, the most impactful shadow might be that of the moon. In the 1878 eclipse, Mitchell described it as “a picture which the sun threw at our feet of the dignified march of the moon in its orbit.” Because of the massive size of the shadow — more than 450 kilometers wide — it is best seen from a panoramic vista. Mitchell described her view from the Colorado plateau in Scientific American: “The sweep of the black shadow was seen as it approached us from the Rocky Mountains, and its retreating darkness was seen to cross the plain to the southeast.” Since the moon blocks the sun’s light differently than a rain cloud or twilight, the shadow is “not the flitting of the closer shadow over the hill and dale.” Instead, the color is unique, Mitchell noted: “Our whole party agreed that the darkness was neither that of twilight nor of moonlight.”

A mountain or high plateau aren’t the only vistas where you can see this effect; the roof of a tall building will do.

As Mitchell’s vivid accounts make clear, a total solar eclipse is an opportunity to see something memorable. But taking it all in is impossible, and that’s OK. “No one person can give an account of this eclipse,” Mitchell wrote, “but the speciality of each is the bit of mosaic which he contributes to the whole.” The mosaic of April 8’s total solar eclipse promises to be a spectacular experience for everyone

source site