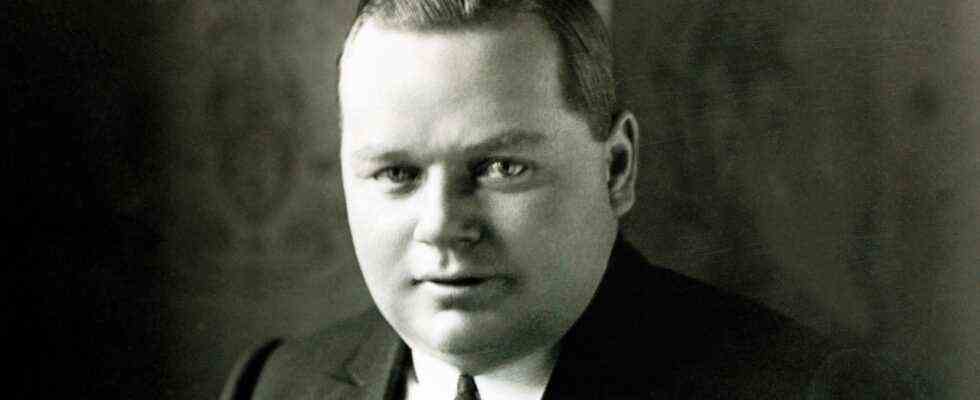

A hundred years ago, on the Saturday before Labor Day, Roscoe Arbuckle drove his plum-colored Pierce-Arrow to San Francisco for a weekend of partying. At two hundred and sixty-six pounds, Arbuckle, known to movie audiences as Fatty, was the Chris Farley of silent cinema, beloved for his pratfalls and for his skill at throwing custard pies in people’s faces. By September, 1921, he had appeared in more than a hundred and fifty films, often in his trademark outfit of baggy pants, suspenders, and an undersized bowler hat; he was earning a million dollars a year at Paramount. In Los Angeles, he owned a twenty-room mansion, complete with servants, Oriental rugs, gold-leaf bathtubs, and a cellar full of liquor that he broke out for jazz-fuelled soirées. The Pierce-Arrow, his thirty-four-thousand-dollar “gasoline palace,” was just one of his fleet of trophy cars, and it likely drew crowds as it whizzed up the coast. Everybody knew Fatty. Even his pit bull terrier was famous: Luke, his co-star in “Fatty’s Faithful Fido.”

In San Francisco, Arbuckle checked into the St. Francis, a grand European-style hotel with its own orchestra and Turkish baths. He and his entourage fanned out into three adjoining rooms on the top floor. Twenty months into Prohibition, booze wasn’t hard to find, especially if you were Fatty Arbuckle, and that evening a shipment of gin and Scotch was delivered from Gobey’s Grill. Late Monday morning—September 5, 1921—a gown salesman named Ira Fortlouis was leaving the nearby Palace Hotel to meet one of Arbuckle’s friends. In the Palace lobby, he spotted another group from Los Angeles and asked a bellboy about the chic young woman with dark hair. She was, the bellboy said, “Virginia Rappe, the movie actress.” Rappe was known to Arbuckle’s group, and they sent word inviting her for afternoon drinks.

Rappe arrived at around noon. A onetime fashion model and designer, she wore a jade skirt and blouse, with a panama hat trimmed with matching ribbon. “I’ll go up there, and if the party is a bloomer I’ll be back in twenty minutes,” she had told her companions, the film publicist Alfred Semnacher and his friend Maude Delmont. Up in Room 1220, Arbuckle was wearing pajamas and a purple bathrobe, holding court with a small crowd of wingmen and showgirls. They ordered up a Victrola and danced to “Ain’t We Got Fun?” More booze came from Gobey’s. Rappe, whose friends had joined the party, drank Orange Blossoms and chatted with Arbuckle. At some point, she went to use the bathroom in Room 1221, but Delmont was in there with Arbuckle’s actor friend Lowell Sherman. So she crossed into Arbuckle’s room, 1219. Just before three o’clock, Arbuckle went in, too, and locked the door.

What happened next was pored over by three juries, a scandal-mad public, and a century’s worth of amateur criminologists. In one version of the story, Arbuckle threw Rappe onto the bed and mortally crushed her with his bulk. In another, he found her ill and tended to her like a gentleman. They were alone together for either ten minutes or an hour, depending on whom you believe. Delmont said that she grew so worried about Rappe that she kicked the door and called her name. Arbuckle said that he opened it unprovoked. Either way, when the other partyers got into Room 1219 they found Rappe barely conscious, tearing at her clothes in agony and complaining of a fierce pain in her abdomen. They put her in a cold bath, and then moved her to another room, down the hall, where a hotel doctor determined that she’d simply had too much to drink. The party continued. Rappe spent three days in the hotel room, her pain dulled with morphine, before she was finally transferred to a sanatorium. Why she wasn’t moved sooner is an infuriating mystery. The next day, Friday, September 9th, she died. On Saturday, Arbuckle was arrested for murder.

The Arbuckle affair was the most notorious in a string of Hollywood scandals that threatened to kill off the movie industry in its adolescence. Decades before Twitter or TMZ, it set the template for the celebrity scandal: the way we gawk at, adjudicate, and mythologize tales of high-flying people brought low, whatever the facts may be. Arbuckle’s deadly pajama party came to epitomize the loosening morals that followed the First World War, and his downfall became a wedge in a culture war. As Greg Merritt writes in his forensic 2013 account, “Room 1219,” “The defenders of tradition were pitted against the purveyors of modernity. On one side, the Victorian era. On the other, the Jazz Age.” But, as much as the scandal evokes old Hollywood, its modern resonances are uncanny: a famous actor accused of sexual assault, a media apparatus eager to capitalize on every salacious twist, and an industry grappling with how to dispose of a once profitable star turned pariah. Ultimately, Hollywood dealt with its first big P.R. disaster by regulating itself so that no one else could, making the Arbuckle scandal an unlikely parable of corporate self-preservation.

Arbuckle’s fall was so novel in part because he represented a new kind of fame. He was born in 1887, in a farmhouse in Kansas. The nickname Fatty was a childhood taunt. Even after embracing it, as the star of “Fatty’s Day Off” and “Fatty’s Magic Pants,” Arbuckle was reluctant to use his weight as comic fodder. “I refuse to try to make people laugh at my bulk,” he said in 1917. “Personally, I cannot believe that a battleship is a bit funnier than a canoe, but some people do not feel that way about it.” He began performing when he was eight, after the family moved to Santa Ana, California, and a theatrical troupe passing through town needed a replacement for a child actor. Arbuckle went onstage—in blackface. (Since he was barefoot, his feet had to be darkened as well.) His mother died when he was twelve, and he was sent north to live with his father, who had abandoned the family and supposedly owned a hotel in the town of Watsonville. By the time Roscoe arrived, alone, his father had sold the hotel and left town. The boy sat sobbing until some locals took him in, and he earned his keep by doing chores and singing for the hotel guests.

Eventually, his father materialized. He would thrash Roscoe in alcoholic rages; his stepmother recalled once rescuing him when his father was “choking him and beating his head against a tree.” The boy had a bell-like voice and sang in vaudeville houses, performing “illustrated songs”—a forerunner of music videos, in which popular tunes were accompanied by slide shows. As a teen-ager, he escaped his father by touring on the Pantages theatre circuit. In 1908, he met Minta Durfee, who was performing on the same bill in Long Beach, and they married on the stage of the Byde-A-Wyle Theatre.

In 1913, Arbuckle showed up at Keystone Studios, a comedy lot known as the Fun Factory and the home of the bumbling Keystone Kops. Its impresario, Mack Sennett, hired him for three dollars a day. That first year, he acted in no fewer than thirty-six shorts, many of them opposite Keystone’s leading lady (and Sennett’s lover), Mabel Normand. The next year, Charlie Chaplin, still developing his Little Tramp persona, joined the studio, and he and Arbuckle acted together in seven films. Along with Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, they were part of the first wave of movie stars to live like—and be covered by the media as—American royalty. By 1915, the fan magazine Photoplay was breathlessly detailing Arbuckle’s ideal dinner, a menu that included crabmeat cocktail, a dozen raw oysters, fried salmon steak, roast turkey, Hungarian goulash, Roquefort cheese with crackers, and cold artichokes with mayonnaise.

The following year, Paramount poached Arbuckle by offering him his own production company, Comique Film Corporation, and a base salary seven times what he made at Keystone. This required him to renege on a smaller deal that would have included his wife, and Durfee was so upset with his maneuvering that the couple drifted into an unpublicized separation. Paramount sent its new prize on a twenty-three-stop publicity tour. As the director of his own pictures, Arbuckle brought on the younger comedian Buster Keaton, who became his frequent co-star and lifelong defender.

The rapid rise of movie stars shook up the balance of power in Hollywood, especially when Chaplin, Pickford, and Fairbanks teamed up with D. W. Griffith to form their own collective, United Artists, circumventing the studios. Amid rumors that Arbuckle might join them, Paramount showered him with cash, in a deal that paid three million dollars in the course of three years. The record payday made headlines, and Arbuckle embraced a life style to match. He bought the mansion, the cars, and, briefly, a baseball team, the Pacific Coast League’s Vernon Tigers, paving the way for celebrity team owners like Jay-Z. Fans mobbed him. He hosted a dog wedding. (Luke was the “best man.”) By Labor Day, 1921, he had seven films playing in theatres, with two more wrapped.

Less is known about the life of Virginia Rappe. Born in 1891, in Chicago, she began modelling at sixteen, appearing in fashion shows at department stores. She changed her name from Rapp to give it a more exotic pronunciation—“Rapp-ay.” Showing a proto-feminist streak of independence, she advised young women in 1913, “Be original—every girl can be that.” She began marketing her own designs, including hats shaped like spiderwebs, submarines, and dove wings (her “peace hat”). As Merritt observes, “If she were designing fashions today, she would surely be a maven of social media.” In other words, an influencer.

She moved to Los Angeles in 1916, one of a sea of ingénues hoping to become the next Mary Pickford. She had a vampy role in “Paradise Garden” (now lost) and a two-and-a-half-year relationship with the director Henry Lehrman, who cast her in several pictures before his production company went under. By the summer of 1921, Rappe was thirty but shaving years off her age, and her multiple careers had ebbed. It was only after her death, as Arbuckle’s movies were being ripped from projectors, that her name became a marquee attraction.

Shortly after she died, a doctor, William Ophüls, examined her body and recorded several bruises on her right arm and her thighs, but no evidence of sexual assault. He cut open her abdomen, and found a hole in the outer wall of her bladder an eighth of an inch wide. Cause of death: rupture of the bladder, owing in part to acute peritonitis. A Dr. Shelby Strange performed a second autopsy that evening, and agreed that the bladder had killed her. But what had ruptured it? Dr. Strange suspected “some external force.”

Arbuckle had already taken a steamship home to L.A. when a reporter informed him that Rappe had died. That night, he attended a midnight meeting at Sid Grauman’s Million Dollar Theatre, along with his Labor Day hotel companions (and soon-to-be witnesses) and, more curiously, Rappe’s friend Al Semnacher. What, exactly, was discussed is unknown, but it’s possible that they were getting their stories straight. In Arbuckle’s initial statements, he insisted that he was never alone with Rappe, which was a lie. Then, on the advice of his attorney, he shut his trap.

San Francisco theatres immediately banned Arbuckle’s films, and Sid Grauman pulled his new picture, “Gasoline Gus,” from the Million Dollar Theatre. Within a week, his movies had vanished nationwide. In one Wyoming theatre, it was reported that a mob of cowboys shot up his image on the screen. (It turned out that the theatre owner had concocted the story for publicity.) Paramount stopped paying its top star eleven days after his arrest, on the ground that he was locked in a San Francisco jail and unable to report to work. The next day, Universal wrote a morality clause into its contracts, mandating nonpayment to performers who “forfeit the respect of the public,” and other studios followed. (Morality clauses have made a comeback in recent years.) The new strictures could have horrendous consequences for the stars; when Gloria Swanson became pregnant by a man who wasn’t yet her husband, she was so afraid of being ostracized that she got a botched abortion that nearly killed her.

The scandal was a media bonanza. Without real competition yet from radio or newsweekly magazines, newspapers were the only game in town, often publishing multiple editions a day. The Los Angeles Times: “PLAN TO SEND ARBUCKLE TO DEATH ON GALLOWS.” The San Francisco Call and Post: “ARBUCKLE DANCES WHILE GIRL IS DYING, JOYOUS FROLIC AMID DEATH TRAGEDY.” The Oxnard Daily Courier: “ARBUCKLE, THE BEAST.” Many outlets used the word “orgy” to describe the Labor Day party. William Randolph Hearst’s papers, which helped pioneer yellow journalism and anticipated the likes of the National Enquirer and the Daily Mail, were particularly sensational. On September 13th alone, Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner ran seventeen stories about the scandal—a harbinger of the twenty-four-hour gossip industry that runs on Schadenfreude. As Swanson wrote in her autobiography, “The newspapers had proved in less than a week that the public got a much greater thrill out of watching stars fall than out of watching them shine.”