This article was featured in the One Story to Read Today newsletter. Sign up for it here.

You could say I grew up not knowing who I was. I knew that I’d been born in an Indianapolis hospital in 1968, and that my parents had adopted me when I was 10 days old. That was it. I didn’t know who my birth parents were, or why they couldn’t raise me. I had no medical history.

If you had asked me in my younger days, I would have said that this didn’t bother me much. I was one of three sons of public-school teachers who filled our house with books and with their love. I had a genealogy—that of my adoptive family. When other kids asked if I wanted to find my “real parents,” I’d say I wasn’t interested.

But this couldn’t have been correct. Kids only asked because they knew I was adopted, and they only knew because I’d brought it up. Apparently, my past meant something to me. In high school, friends said I sounded like David Letterman, who was from Indiana and old enough to be my father, and I wondered about that for years. Yet I made no attempt to search for my birth parents. I knew that some people who tracked down their birth families didn’t like what they found, and I had a family I didn’t want to hurt.

I grew up to become a journalist, exposing hidden facts, and a writer of history, seeking meaning in the past—but avoided my own story until I received an external push. It happened in 2012 as my wife and I prepared to adopt a daughter. Unlike having a biological child, which we also had done, adoption requires you to let strangers judge your fitness for parenting. We filled out forms, attended meetings with other parents, and submitted to a home inspection by a social worker. She observed that we were about to adopt from China, where records commonly list children in orphanages as abandoned, with no family history. She said the child might ask questions about this, and suggested a tool for addressing them: I should try to learn my own past.

Did this make sense? I didn’t see how learning my story would help my daughter, and I wondered if the social worker was really trying to help me. But I dutifully sought information in the same way I had learned to cover the news. My feelings didn’t matter, only facts did.

In the past, my search would have been difficult or impossible, forbidden by custom and law. For much of the 20th century, adoptions were cloaked in secrecy. State laws sealed birth certificates and other records, keeping them from even the adoptees themselves. But I was faintly aware that adoptees and their families were pushing for change. For nearly as long as I’d been alive, they’d been arguing that secrecy was a human-rights violation. They demanded equality—the same access to their birth records as anyone else.

This movement had led Indiana to enact a modest reform: a voluntary adoption registry. I enrolled, but the state said no other party to my adoption had left their name. Next I called the Children’s Bureau of Indianapolis, the agency that had placed me in 1968. A worker there said she had my records in her hands, but she wasn’t allowed to share them with me. She proposed to act as my intermediary instead. She called a woman who seemed to match the description of my birth mother. Informed of the purpose of the call, the woman answered, “That was a long time ago,” and hung up. The worker next offered to forward a letter from me. I wrote and never heard back.

My wife and I went ahead with our own adoption, and I set aside my past. But I knew now that someone had information about me. It was part of my identity, which my state had seized. Learning that records were out there—not just a birth certificate but a file showing who my birth mother was and where she came from—made it harder for me to suppress my interest in what they said. This was my story too. What right did the state of Indiana have to keep it from me?

Long after I was grown, my mom gave me a few artifacts of adoption as practiced in 1968. They included a white “memory book” called All About You that parents could fill with facts and baby photos. The Children’s Bureau had distributed it as a tool for telling children they had been adopted. The agency knew that some adoptive parents hid the truth, fearing that their children might feel traumatized—or stop loving them.

In an accompanying pamphlet, the memory book’s creator confessed that even she had been “tempted” not to tell her adopted daughter, but decided she must: “From the day your child comes into his new home, his story is vital to his sense of security.” Adoptive parents were advised to be honest.

Mine were. They had experience from adopting my older brother. They told me early and fielded my questions. (Once, when I was small, I walked into the garage and asked my dad how much I had cost. Seventeen dollars was the figure in my head. He said adoption didn’t work that way.) But they could not have answered my biggest questions. Not even All About You could say all about me, because so much had happened before the first page of the book.

This was near the peak of the “baby-scoop era,” the decades following World War II. Birth rates soared, as did out-of-wedlock births. Adoption rates also soared, and secrecy laws in 48 states helped agencies provide babies with no history for adoptive parents to embrace. Several million children changed hands in this period.

Secrecy fit a mid-20th-century sensibility—the impulse to leave uncomfortable truths unsaid, like World War II veterans who never talked about their service, or the John Wayne character in The Searchers who avoids telling a man that his fiancée is dead: “I thought it best to keep it from you.” Adoptions tended to follow circumstances that society viewed as moral failures—a birth outside marriage, divorce, substance abuse, mental illness, poverty. A parent’s decision to surrender a child was itself hard for many to comprehend. Some people assumed that the children must be damaged. The less said, the better.

From that perspective, secrecy was a kindness to all involved, and when I was growing up, it seemed always to have been the rule. Later I learned that the laws were not so old, having developed haphazardly across the early decades of the century. States began concealing adoption records during the Progressive era, and the original goal was not secrecy but privacy. Minnesota lawmakers were the first to establish “confidential” adoption in 1917. That law shielded birth records from public scrutiny, but people could still view their own information.

This was akin to modern medical privacy, and if all the rest of the country had copied Minnesota, the result would have been hard to criticize. Instead, states experimented with other formulas. Two states and the District of Columbia simply erased all identifying information from the birth records of unmarried mothers and their children. (An alarmed federal researcher said that this produced children who “are truly no one’s,” with no means of “satisfying their desire in later years to know something of their own people.”) In the 1930s a reformer, Edna Gladney, persuaded the Texas legislature to delete the word illegitimate from birth certificates. It was considered a mark of shame, which Gladney knew well because she had one herself. She soon endorsed a new approach that was spreading from state to state. Rather than erasing information, some authorities were recording an out-of-wedlock birth as illegitimate, then sealing the record. When people needed a birth certificate, states offered a second one with the names of adoptive parents—“a birth certificate as it should be,” Gladney said when this process became Texas law. The reform seemed so benign that in 1941 Indiana’s House of Representatives approved it 70–0.

E. Wayne Carp, the author of a book on the subject, writes that agencies and social workers enforced a culture of secrecy. Some hid even more information than the law required, fearing that birth parents might “harass” an adoptive family. When adoptees asked one Seattle agency for facts about their birth families, employees labeled them “disturbed” or “sick.”

Secrecy might have continued indefinitely if not for some children who grew up to undermine it. One was Pam Kroskie, who, like me, was adopted in Indiana in the late 1960s. After she had a baby in her early 20s, she resolved to learn her ancestry. She obtained a document from the doctor who’d seen her as a baby, and discovered that it showed an ID number from her infant hospital bracelet. She used this number to request hospital records that showed her birth mother’s name. Kroskie dialed the woman’s phone number over and over, listening to the ring so many times that she was taken by surprise when her mother finally picked up. They met at Kroskie’s home in 1990. “I cried,” Kroskie told me—and her birth mother also wept when Kroskie’s 18-month-old son wandered into the room. The boy had red hair like his grandmother.

Their relationship lasted until the birth mother’s death two decades later, and Kroskie became active in the American Adoption Congress, which advocates for reform. Like many adoptees, she speaks of the power of having a “mirror”—seeing someone who looks like you. Beyond that, she told me, “this was about just knowing your name, how much you weighed at birth, where were you born—things that everybody else already knows.”

In recent decades, open adoptions have become the norm. A lot of adoptees grow up knowing their birth parents, or at least knowing about them. Adults who still lack this information have gained new tools to puncture secrecy: the internet and DNA testing. Commercial DNA databases can help identify unknown relatives or show that people are not related. (Kroskie told me she took a DNA test and learned that her birth mother had misidentified her father—a secret within her secret.)

But many people still can’t find their identity without access to their paper trail. Most states have opened at least some records, but the two most populous—California and Texas—have not. According to the Adoptee Rights Law Center, only 14 states allow all people equal access to their birth records.

When I began researching this topic, I was surprised that secrecy laws remain on the books even in states where majorities of legislators seem to favor change. In Maryland, the House approved open records almost without opposition, only for the idea to fail after passionate debate in the Senate in 2021. In Texas, reform has passed the House but, in recent years, has not even come up for a vote in the Senate. Activists there believe that a single influential state senator, Republican Donna Campbell, has stood in their way. Campbell once told Texas Monthly, “I am an adoptive mom who understands the unintentional consequences of this bill.” If a birth mother agreed to a closed adoption, Campbell added, the government should not try “to undo her decision.”

Campbell didn’t return my calls or emails, but conversations with people involved in the issue gave me some idea of why change is hard. When Louisiana considered opening its records in 2022, opposition came from a group called Louisiana Right to Life. Its communications director, Sarah Zagorski, who testified at a legislative hearing, agreed to talk with me.

At the start of our call, I disclosed that I had a point of view, because I am adopted. “I also have a very strong point of view,” she said, “and I am also adopted.”

Zagorski said she wanted to protect birth mothers who needed confidentiality. Without secrecy, “the one way she can get confidentiality is a $500 abortion.”

I said I didn’t think the history of secrecy quite matched what she said. Confidential adoptions in the early 1900s may have shielded mothers and children from shame, but secret adoptions went beyond: Birth mothers were not receiving privacy so much as signing away the right to know anything of their children.

Zagorski said she had heard such claims during the hearing but still felt that women might need to hide secrets like “rape or incest.”

Abortion opponents have long promoted adoption as a vital alternative. It came up even in the Supreme Court case that eliminated the constitutional right to abortion. During oral arguments in 2021, Justice Amy Coney Barrett, an adoptive mother herself, asked if state “safe haven” laws solve the “problem” of unwanted pregnancies by making it easy for women to surrender children for adoption.

Advocates of open records have tried to keep their issue separate from abortion. Adam Pertman, an author and adoptive father, compiled statistics showing that states without secrecy laws had lower abortion rates than the nation as a whole. And many conservatives have backed adoption reform. A sponsor of Louisiana’s open-records bill was an adoptee who opposes abortion rights, and his bill passed the conservative legislature despite the opposition from Louisiana Right to Life. In Texas, where almost all abortions are banned, an anti-abortion group is even promoting open adoption as a way to give birth mothers “choices.”

Yet in Texas, as in so many places, birth records remain sealed.

The lingering support for secrecy rests on an assumption: that while adoptees might demand openness, birth mothers want to stay in the shadows. In earlier generations, families did send away pregnant daughters to give birth out of town, and some of those daughters built new lives without ever disclosing their past. Today, some people taking DNA tests discover half siblings whom their mothers never mentioned.

This doesn’t mean that most mothers truly approved of a system that gave them little choice or control. Many were told they must relinquish their babies in secrecy or ruin their lives. Certain abuses were possible because the parties never met—like a “baby black market” exposed by a Kansas newspaper in 1955. Attorneys were charging adoptive parents high fees that they said would support birth mothers, when in fact the lawyers were pocketing that money themselves. In other cases, mothers grieved for children they felt forced to surrender, and had no way to learn what became of them. Some mothers pleaded for photos of their children, only to be denied. It’s not surprising that in recent years, as mothers have gained more power to negotiate the terms of an adoption, many have insisted on some future contact with the child.

One of the advocates for reform in my state is a birth mother, Marcie Keithley, who co-founded the National Association of Adoptees and Parents. She learned she was pregnant in 1978. “I was really in denial about it,” she told me. “I was a very immature 22-year-old.” She put off decisions, telling herself that her boyfriend was going to marry her. When he didn’t, she had no one to advise her except her doctor, who said he knew a childless couple. He took over the process—Keithley said she felt pressured—and brought documents for her to sign, although “I had no legal representation.” Weeks after Keithley gave birth to a baby girl, her boyfriend had second thoughts, and they asked the doctor about revoking the adoption. The doctor declined to help, which Keithley described to me as “soul-shattering.”

Thirty years later, she reconnected with the boyfriend and they married. They decided to find their daughter, and thanks to a “search angel,” a volunteer who scours public records to reunite people, they learned she had left her name with an adoption registry. Keithley and her daughter are now in regular contact.

Keithley teamed up with Pam Kroskie and others to challenge Indiana’s law. Eventually they hired a lobbyist and in 2016 met with then–Indiana Governor Mike Pence. Pence opposes abortion, but he listened carefully, and was sympathetic. The bill he signed did not provide equal access, but it did allow any party to an adoption to obtain their records so long as no other party had previously filed an objection.

The law took effect in 2018; I requested my records at the start of 2019. A month later, the state acknowledged my request without fulfilling it. So many people were demanding their files that Indiana’s adoption registry was overwhelmed.

The idea of seeing my files filled me with as much dread as anticipation, but I am a reporter, and having asked a question, I expected an answer. I worried that someone might file an objection before I could learn my story—which I apparently wanted after all. In March I sent a follow-up email. On July 1, I wrote again, this time quoting the law: The state “shall release identifying information” upon request. I wrote that excessive delays would amount to denying my request unlawfully.

On July 2 the state replied: “Your request went out yesterday.”

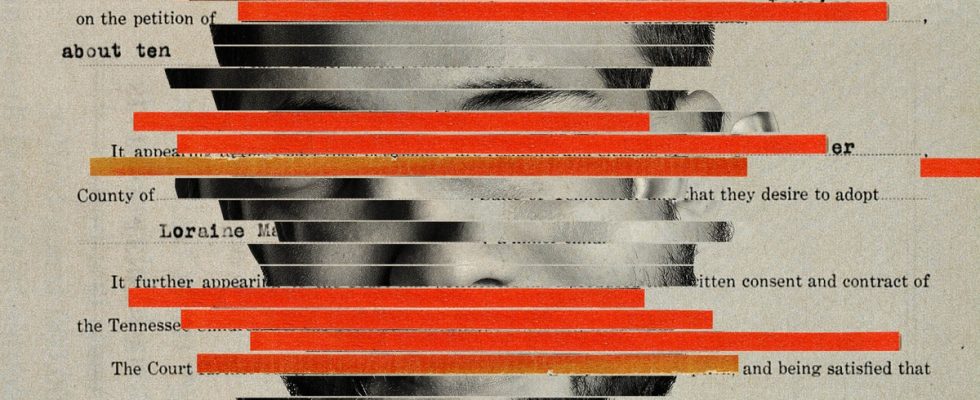

When the envelope arrived in the mail, I went off by myself to read. The papers were plain and mostly typed. My birth certificate had my mother’s full name, which I’d never seen. Getting used to the look and sound of it took time. The space for my father’s name was blank. There was a box labeled birth weight—seven pounds, two and a half ounces—and another labeled legitimate, in which the typed answer, capitalized, was “NO.” My story had been hidden from me for half a century to keep anyone from seeing that little box.

I told the Children’s Bureau that the state had released my records, and asked for its file, the one the agency employee had held in her hands back in 2012. They sent my birth mother’s fingerprints, which are on a piece of glossy paper along with my then-tiny footprint. My file also included several pages of single-spaced text: Two caseworkers had typed narratives of their meetings with my birth mother, which are a primary source for the account that follows.

My mother was not from Indiana but from a small town in eastern Kentucky, at the edge of a coal-mining region. This fact alone was a revelation. I had attended college in that same area, at Morehead State University, a short drive from my mother’s hometown. I may have sat in classes with her relatives, which is to say my relatives. The yearbook from my graduation year includes 15 people who shared her last name.

She grew up in one of the poorest parts of America, where logging and mining had enriched distant companies while leaving most residents empty-handed. Even today her home county, like many in that part of Appalachia, is on a Census Bureau list of counties with decades of “persistent poverty.” In the mid-20th century, those places were far more isolated.

Her father, a farmer, died in an accident when she was young, and as a teenager she moved north in search of work. Just as Black Americans left the Deep South for northern cities during the Great Migration, poor white people were making a parallel migration out of Appalachia. Many of her fellow migrants found factory jobs (a Johnny Cash hit of the era tells of a man who “left Kentucky back in ’49” to work on an “assembly line”), but her one semester of college probably helped her find an office job as a personnel clerk in Ohio. Women’s liberation was accelerating in the 1960s, and she enjoyed “a great deal of freedom and independence as well as a rather comfortable way of living,” according to a caseworker’s notes. Then she fell in love with a married colleague and discovered she was pregnant.

The year 1968 is remembered for protests against the Vietnam War, for the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, and for a widespread feeling that the country was coming apart. Amid these public crises were many private ones like my mother’s. One hundred sixty-six thousand children were placed for adoption that year, the most of any year on record up to that time.

She believed that her co-worker loved her, but he was not going to leave his wife and twins. He offered financial support, but she refused. She didn’t ask anyone else for help either. “No one knows about her pregnancy in her family,” a caseworker noted. “The only person who knows is the putative father.” My mother didn’t even see a doctor for prenatal care, and quit her job before her condition was obvious. On a Thursday night in June when she was about nine months pregnant, she drove west out of Ohio with no definite plans.

Indianapolis was the first big city she encountered. She checked into the Arlington Inn—$10 a night—and it’s not hard to imagine her sitting alone on the bed like a woman in an Edward Hopper painting. She placed her weekly call to her mother in Kentucky, but didn’t say where she was. And she at last visited a doctor, who referred her to the Children’s Bureau. A caseworker described her as “a very attractive, sweet looking girl, who seems to have come from a good family and is intelligent.”

Because she had no one to talk with, she had never put her plans into words, effectively keeping the secret even from herself. She “was requesting that the baby be placed for adoption but admitted that really today is the first time that she has talked about this and she seemed somewhat upset about stating that she will be placing her baby.” The caseworker spoke of “the need for her to face the situation” and to make a decision, to which she replied that she had no decision to make: “She feels that she cannot keep the baby as she would not be able to meet all of her responsibilities and provide for it adequately.”

She returned to the Arlington Inn—it was Friday afternoon—and went into labor that weekend. She called a taxi to take her to the hospital, went down to the lobby to wait for it, and “didn’t feel that anyone was aware that she [was] in labor.” She went through the hours in the hospital with nobody to hold her hand.

Two days later a caseworker visited the hospital and “asked her how she felt about the experience now that it was all over. She immediately started to cry and apologized for doing so.” The caseworker suggested giving some thought to her relationship with the man she identified as the father. She replied “that she felt she had done enough thinking” and “was ready to go on to other things now.”

Her baby went into foster care, and she signed her consent in left-leaning cursive. At a final meeting before she left town, the caseworker noticed that she already fit into her old clothes. Her waist was tiny, and she said she had let out her belt only one notch from before she was pregnant. She was young, and had a future; she imagined returning to college. She showed up early for that final meeting, hurried through it, and was gone.

When I learned this story, I told my brothers, and we discussed whether to tell our mom. It might distress her, and she would receive the news alone, because our dad had died years earlier. But her name was in the files. It was her story too. When I finally told her, she listened quietly, asking only a few questions.

Later, she apologized. I said she owed me no apology; she hadn’t made the rules. She answered that she was sorry for feeling that she might lose me if I found out. She hasn’t.

It wasn’t hard to locate the person I believe to be my birth mother. Having sent that letter back in 2012, I hesitated to try again, but I wrote another last spring. It felt like the right thing to do before we die. I told her how my life had turned out, enclosed photos of her grandchildren, and invited her to reply when she was ready. She hasn’t written back, and maybe never will—and I’m at peace with that. My files had told me a lot, and I have since learned more.

My wife, Carolee, is a genealogist who takes no record as fact without confirmation. She located documents and articles that backed up much of what my birth mother had said. Carolee also reconstructed something of my relatives’ lives, and nudged me to take DNA tests—all of which produced revelations beyond the Children’s Bureau files.

The first was that, according to public records, my mother was married at the time I was conceived. An Ohio marriage license lists a woman with the same first and last name, same birth date, same Kentucky hometown, same father, and same occupation. The only variation is the spelling of the middle name, which changes slightly on various documents over time.

In 1966 she married a sergeant in the military, who was soon stationed in the Philippines. Their marriage came apart while he was away, and both sued for divorce. At the time of the final hearing, she would have been about eight months pregnant, but the court records made no mention of this, and stated there were no children “born of said marriage.”

It was while her marriage was collapsing that she had the relationship with her co-worker, the “putative father” mentioned in my adoption records. She knew a lot about him, such as the names and occupations of some of his relatives. (As I write this, I am astonished all over again that the agency meticulously gathered my genealogy while knowing it must never tell me.)

This man is deceased, but I contacted his sister, who is named in the Children’s Bureau files. She confirmed that the information about her in the files was correct. She added that she had heard a family story about her brother fathering a child out of wedlock. He may have lived and died believing that he was the father of a child he’d never known.

But if he believed this, he was mistaken. I can say that because of another revelation, which came from the DNA tests. His sister agreed to my request to take two of them, knowing that if her brother was my father, we would share considerable DNA. We do not.

Evidence, as processed by Ancestry and 23andMe, points toward another man, also deceased—neither the husband nor the co-worker. Public records and news articles suggest that he, too, came from Appalachia, and migrated north to Ohio. Taken together, documents and DNA tell a story about three men—one who went overseas, one whom she loved and could not have, and one who was my father. Caught in a tangled situation, she gathered her strength and managed to extricate herself. She left her child in a safe place and went on to make a new life far away. It was probably the best she could have done.

This, then, is my history, to the extent that I know it now. I still don’t know how it will help my daughter, though it’s here when she wants it.

Did it help me? If that was the social worker’s intent, she was right. I like knowing how my story fits into my country’s recent history. I’m also amazed by my birth mother’s road trip that made me a native of Indiana and brought me to my family. Had she steered in a different direction, I would have a different life. A lot of human history is just people responding to desperate circumstances. It’s not hard to feel compassion for her.

Some might say I didn’t need to know my story, because I turned out all right, but this has things backward. I’m not the one who had to prove a need for my own identity. Indiana had the burden of showing why the state needed to take it. So long as my records were hidden, the state could offer theoretical justifications, but those reasons vanished for me the instant I knew the truth.

For those who feel they need protection, respect for confidentiality should be enough. An adoptee can choose to share their story or not—and the same is true of a birth parent, which is why I have tried to approach mine with discretion, and left out of this account any details that might be used to identify her. But we have a right to our own history. Once I’d read my files, I knew exactly how I felt: that I always should have known these facts. That there was no shame in knowing them. That there was nothing to be afraid of.