At the press preview for the 58th Carnegie International—titled “Is it morning for you yet?”—I heard its curator, Sohrab Mohebbi, make an admission I don’t recall hearing from the mouth of any curator ever before. He was explaining the exhibition’s bipartite structure, the “two dialogical tracks” that he and his colleagues had contrived: a contemporary track focusing on new works, and a historical track tracing “the geopolitical imprint of the United States since 1945 to situate the ‘international’ within our local context,” as he writes in the exhibition catalog. Mohebbi, the recently appointed director of the SculptureCenter in the New York City borough of Queens, was explaining that these two parts of the show were meant to remain distinct yet intertwined. In other words, he had—like any well-trained curator today—a clearly framed rationale for the show he had planned. He explained all this, and then smiled and said, “But then the art did something else.” At that moment, I began to suspect that I was about to see an exhibition more interesting and complicated than I had bargained for, just as had apparently happened to Mohebbi himself—an exhibition that allows for an aesthetic experience more powerful than the intellectual principles under which it was organized can account for.

On view from now until April 3, the International is the oldest recurring exhibition in North America, having first occurred in 1896, the year after the inaugural Venice Biennale. This time around, I was even more eager to see it than usual, because the vast majority of the artists and collectives whose work featured in it were completely unknown to me. Sure, there were favorable signs in the mere handful of names that I did recognize—for instance, Andy Robert, a Haitian-born, New York–based artist whom I think of as one of the most interesting younger painters around. I was a little surprised at his inclusion, because he hasn’t gotten much public attention except for his inclusion in last year’s iteration of “Greater New York” at MoMA PS1. Yes, a good sign, suggesting to me that Mohebbi might be not only looking beyond the obvious but doing so with keen judgment, and in many ways this proved to be the case: The Carnegie International, which included some very political entries, did not include any art where the work was simply instrumentalized to the benefit of a political idea.

In other ways, however, Mohebbi’s intention—that the historical part of the show locate “the geopolitical imprint of the United States”—did seem to miss its mark. But this failure, to my mind, turned out to be more of a strength than a weakness of the show, for it meant a decentering of our attention away from the United States and from others’ responses and reactions to it; it meant that one could see the far-flung anticolonial movements of the postwar era as truly creative movements in their own right, and not merely as movements against the power they were trying to overthrow.

Mohebbi’s catalog essay proclaims adherence to a poetics of flight and ambiguity. “Sensing what is not there and unsensing what it is there,” he writes, “are abstraction’s means of pulling away and diverging from the politics of reality toward the invigorating force of life that dissolves the subject/object into being.” Yet he can at times become quite explicit, even prescriptive, about the lessons one is meant to take away from some of the works in the show—that Vandy Rattana’s lush color photographs of Cambodian rice fields, for instance, remind us of the vast destruction unleashed by the millions of tons of bombs the United States dropped on this terrain. The effect of the American bombing campaign on the Cambodian landscape is undoubtedly the subject of the work, and as viewers we would not grasp what we’re seeing without this being known. But is the purpose of the work precisely that the viewer, if American, should take away from an encounter with it a salutary shame at what their forefathers did to the country where the artist (who now lives in Taipei) was born a decade later?

There is, I think, more to it than that. Rattana’s website records his view that photographs are inherently “fictional constructions, abstract and poetic surfaces, histories of their own.” To evoke fiction and poetry in this context does not mean that in suggesting that what we see as simple pools of water originated as bomb craters he might be misleading us. It means that what we see (or think we see) in a picture—or, indeed, what we see on the spot in a place whose history is unfamiliar to us—is conjecture at best. The image may be a surface, but its meaning is below the surface, and that’s what makes the surface resonant.

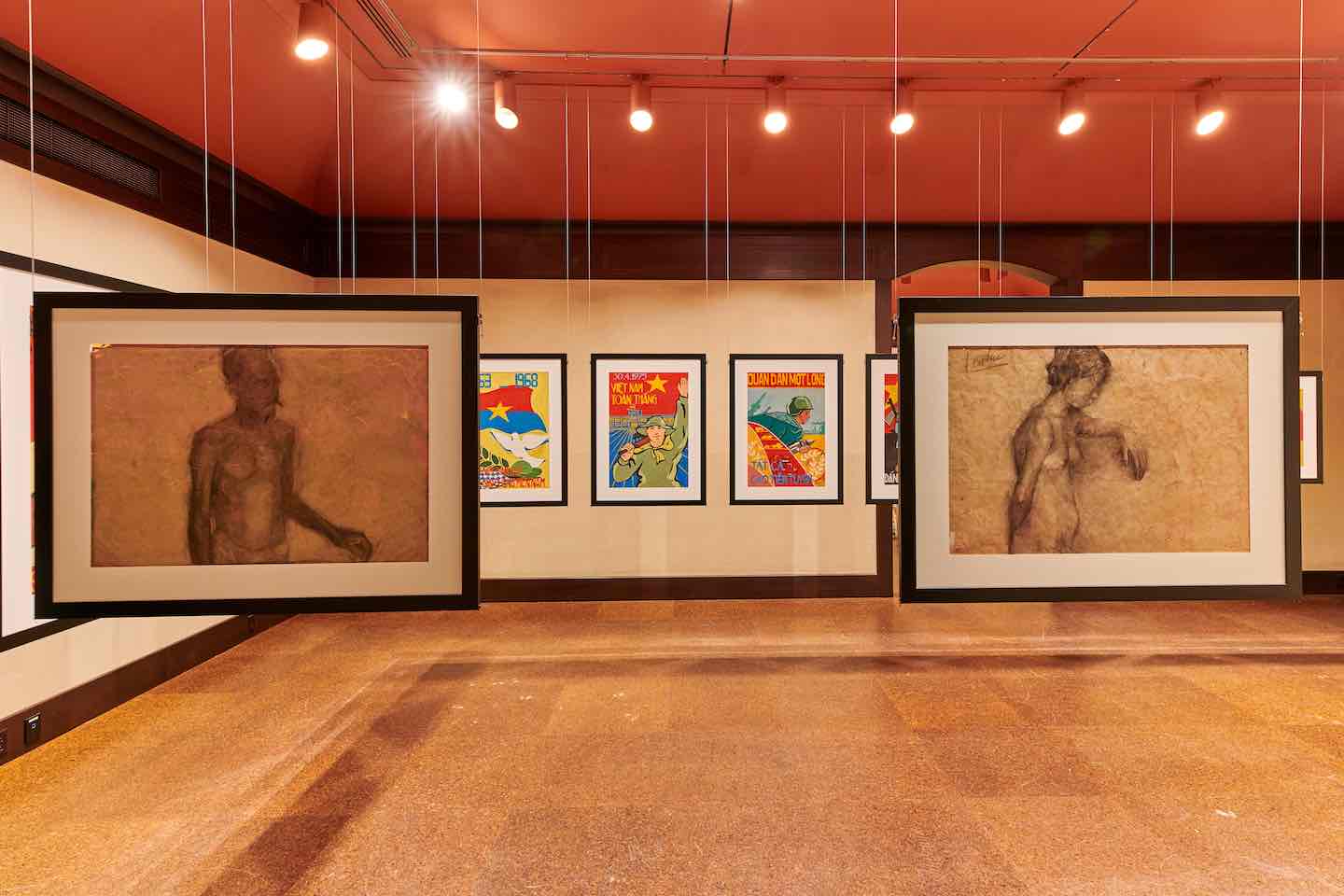

I’m not sure whether Mohebbi intended Rattana’s photographs to be understood as part of the historical or contemporary part of the International. They certainly illustrate—in the most literal way possible—what Mohebbi called “the geopolitical imprint of the United States” on the artist’s homeland. And dating from 2009, they are neither quite new works nor ones that are yet historical in the way of, for instance, a group of 16 colorful Vietnamese propaganda posters from around the late 1960s or early ’70s. These hand-painted posters carry such slogans (but in Vietnamese, of course) as “Fight until the US takes flight and Nguỵ [Republic of Vietnam] collapses” and “Clasp the gun with faith, for our beloved South.” What makes these particular posters even more poignant today is what is also found on their versos: Because paper was scarce during wartime, they were used by art students for their studies in traditional (Western) beaux arts draftsmanship—for studies of the nude model.

At times the disconnect between the images on the two sides is tragicomic—for instance, with a poster depicting a blue-uniformed young woman (with her neckerchief, she looks a bit like a Girl Scout) gazing boldly out at the viewer as she shows off her automatic rifle. Attached to the rifle is a Viet Cong flag with a yellow star on a field that is red above, blue below. The whole poster follows this modernist color scheme of primary colors plus black and white, except for some pink on the girl’s face. To her left is the legend “I’m also a soldier to chase away the American enemy.” Yet the other side of the vertically oriented poster is a horizontally oriented study of another young woman: a seated nude, shown from the waist up, with a far-away look, implicitly melancholy. Done in charcoal, the drawing is sensitive and atmospheric; instead of being centered on the page, the subject occupies its left side, and the blank right side seems to resonate with the woman’s unspoken thoughts—which, of course, are not to be summed up by any such sloganeering as fills the otherwise empty spaces of the poster on the recto. On the other hand, it might be overreading to impute any particular interpretation to this composition; perhaps it was simply a scholastic exercise with no purpose beyond the development of technique. The fact is, the intentions of the artist—anonymous, just like the painter of the propaganda poster on the other side—can never be verified.

There is something fascinating about the dichotomy embodied in these pieces, and it is one that was probably never intended by either of the artists who used this one sheet of paper. Either way, I would probably not go as far as the Carnegie International’s staff, who provided a wall label that states:

While the posters call for militant resistance against US forces in Vietnam and are designed to incite nationalist fervor, their reverse shows war-weary figures rendered vulnerable, fragile, desired, and beautiful, against blank, indeterminate backgrounds. On one side, these works show bodies in service of state ideology, and on the other, bodies in formation and momentarily emancipated from imposed obligations.

Academic representation is an ideological constraint too, after all.

In France—which had presumably exerted influence over Western-style art education in Vietnam—the academy had always been a protectorate of the state, whether under the monarchy or the republic, and was severely hierarchical in its structure. The study of the nude was at its foundation, but it was hardly concerned with plumbing the soul of the model, and any expression of vulnerability or fragility was inimical to its idea of beauty and desirability. If the tenderness and care that an unknown artist, in a workaday exercise, lavished on the depiction of an equally unknown model now seem strangely poignant, this is in part because the two sides of the sheet—the modernist call to arms and the traditionalist contemplation of the human body—have come into an unexpected dialogue. The idealism they both conjure is compelling in its own right, but it is the incongruity of the pieces that is particularly revelatory. Like so much in history, the two pieces of art, joined but facing in opposite directions, don’t add up.

I’d have liked to know more about the Dogma Collection, where these pieces reside. The Carnegie International catalog describes it as “a private collection based in Vietnam,” one that “comprises a large, unique archive of visual art materials reflecting the years before and immediately after Vietnam’s emergence as a unified nation in 1975, and contains propaganda paintings, combat art, photography, and stamps.” Who amassed this collection, and how? That must be a fascinating story in itself.

Much of the historical material in the show, in fact, comes from far-flung archives and collections. There’s the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende Collection (MSSA), which was established in 1971, the catalog explains, “to promote the donation of artworks from artistic circles in the Americas and Europe to Salvador Allende’s Unidad Popular (Popular Unity) government in order to create a museum for the people of Chile,” and which continued in exile after the coup of September 11, 1973, as more works were donated to protest the dictatorship, before returning to Santiago following the restoration of democracy. The collection, as seen here, includes work by some internationally prominent artists of the era—Derek Boshier from London, Öyvind Fahlström from Sweden by way of New York, Ernest Pignon-Ernest from Paris—along with pieces by a great many Latin American artists, including several anonymous arpilleras: embroidered patchwork textile pictures that were often used to denounce the Chilean dictatorship.

The MSSA exemplifies what Mohebbi calls “refracted solidarity: artists responding to movements, retaining common entanglements and cross contaminations.” Similar in this, though less urgent, is the Poema Colectivo Revolución, created between 1981 and 1983 by the Mexican group Colectivo 3, which asked hundreds of artists around the world to fill in a letter-sized template they’d designed with something exemplifying a thought on the concept of revolution. Perhaps it’s the more abstract nature of the project, or the standardized format provided for the varied responses, that makes this a less compelling body of work overall—despite the inclusion in it of a good many beautiful and imaginative individual contributions—than the MSSA occasioned.

A large room is given over to the Laal Collection, assembled by Fereydoun Ave, an Iranian artist and curator, born in 1945, who in the 1970s was the artistic director of the Zand Gallery, a pioneering Tehran venue for avant-garde art. After the Islamic Revolution, he continued to present exhibitions at a much humbler space (described as “an erstwhile garden shed)” called Vanak 13. In Pittsburgh, we see more than 60 small works dating from the late 1950s through just a few years ago, though more than a few are listed as “date unknown”—a sort of total immersion in an art history that is completely unknown to Western art lovers, thereby creating a salutary sense of confusion and wonder.

How to bring one’s already established set of values to such a rowdily diverse and unfamiliar group of works? Better, I think, to hush the voice of critical judgment for a while and learn how to discern the qualities of this art on its own terms. At a minimum, I left feeling that I understood much more about the context that produced a number of artists who grew up in Iran and later made their names abroad—Tala Madani, for instance, and Shirazeh Houshiary. Suddenly, I began to see their work as part of a different continuum and wished some examples of it were here for comparison’s sake.

One of the most precious things about this exhibition is the way it reminds me that my scale of aesthetic values, however passionately held, is contingent and tentative. There are more things in heaven and earth than it has yet encompassed, and more things that it may have the capacity to comprehend. Allied with this is the International’s emphasis on art and imagination as a collective as well as individual endeavor. I can’t tell you if I saw any masterpieces in the Laal Collection or the MSSA, but I can assure you that my experience of art was deepened by getting to know them as totalities, and I wish I could spend more time learning to understand them—which would mean, I suppose, going to live for a while in Tehran or Santiago and becoming, in a way, a different person.

But because I’m not a different person, I can add that while Mohebbi’s show succeeded in making me more sensitive to the collective dimension of creation, I was also able to find outstanding single works of art throughout. Evidently, these are not opposing perspectives but ones in dialectical relation. For me, the show’s great revelation was the Balinese artist I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasi, who went by the name Murni. The show includes a large group of her paintings, mostly acrylic on canvas, made between 1994 and her death in 2006, at just 40 years old. Her art is almost naively colorful and graphically bold, but blatantly violent and sexual in content. I don’t imagine that Murni was aware of the Chicago artists of the Hairy Who group—Jim Nutt, Gladys Nilsson, et al.—or the Berlin-based American feminist artist Dorothy Iannone, but her funny yet painful, raw yet elegant works suggest an analogous sensibility. Murni seems to have been one of those rare artists endowed with the ability to encapsulate her feelings in images without judging them—observing them with a certain neutrality, as if they belonged to someone else. Her paintings are full of bodies undergoing strange transformations; they are usually headless, as if to deny any specific identity, although Murni’s titles often use the first person: In Aku menyembahmu (I worship you), from 1994, a naked woman’s arms preternaturally lengthen, becoming larger than the rest of her body, to grasp at a detached blue penis that seems to be flying off the canvas, while in Kenikmatanku 27 (My Pleasure 27), from 1998, another female body—this one cut off by the canvas at the feet as well as at the shoulders—sports a half-open pair of scissors between her legs.

Like Vandy Rattana’s photographs, Murni’s paintings are not new, though they have never been exhibited in the United States before. But I don’t want to give the impression that rediscoveries overshadow the new works in this show. By asking viewers to question their aesthetic presuppositions, Mohebbi has succeeded in crafting an effective context for approaching new works. If I haven’t left myself much room to discuss them, it’s my fault, not his. At least I can point out a few of the pieces that visitors to this sprawling show should not miss. One is a large audiovisual installation by the Amsterdam-based Indonesian artist Julian “Togar” Abraham, whose title, OK Studio (2020–ongoing), suggests that it might be an extension of his everyday working environment. Using, as the artist explains, “three MIDI keyboards, all connected to one computer; a drum playing automatically; a gong and an ocean drum that are not in sync; a TV playing sounds of ocean waves that I’ve recorded; and a speaker emitting a recording of rain sounds,” it creates a calm yet complex aural environment that feels like the perfect balance of the synthetic and the natural. On the walls surrounding all this equipment, he has hung sign-like paintings in primary colors bearing slogans such as “Sharp Attack Gentle Decay” and “Is What You Share Is What You Get Is What You Breathe.”

Also text-heavy, but far darker and more austere in feeling, is Free Britney?, by the American video artist Tony Cokes. In Cokes’s work, words take the place of image, but reading has a rhythm that subliminally communicates feelings in its own way. The Iraqi artist Ali Eyal almost seems to do the opposite in an installation of drawings on manila envelopes, “Where Does a Thought Go When It’s Forgotten? And.” One might sense that these pieces communicate very specific messages, even though it’s impossible to say what they are; the messages must be intended for someone else. And I’ve already mentioned Andy Robert: His four massive new abstract paintings, each titled Cargo, are strangely as intangible as they are strikingly physical; they seem to keep taking themselves apart and putting themselves together as you look at them. In a way, they stand for the way the whole exhibition disperses itself into distinct parts and then beautifully meshes again