Even Elisabeth Borne mentioned the concept this Wednesday in her general policy statement. “The ecological revolution will not go through degrowth,” she declared. One more proof that this economic, political and social concept gives rise to much debate.

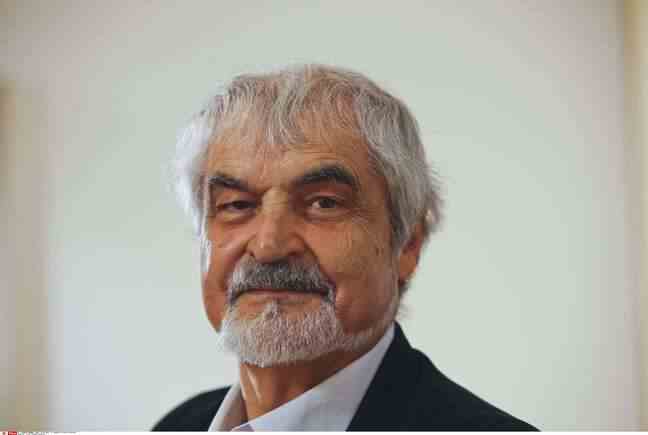

Economist Serge Latouche himself explored it in several works during his career. The first of them, The wager of decline, released in 2006, was just republished a few weeks ago*. “A way again not to push to overconsumption: no need to redo yet another book on the subject when the first summarized everything”, smiles the economist full of good-naturedness.

More than fifteen years later, despite the social and ecological crises, degrowth remains an idea that is sometimes still vague for the general public and is struggling to find its place in public policies. For 20 minutes, the economist explains why.

Let us state the terms straight away: what is degrowth?

Even before being a concept, degrowth is a slogan, launched in 2002 to face another, mystifying one: “sustainable development”. This is an alternative project, not to growth, but to its mindless worship. It is this nuance that is misunderstood, or brushed aside in bad faith, especially in the current political debate. Admittedly, thanks in particular to Delphine Batho (former Minister of Ecology under François Hollande and president of Generation Ecology), the concept of degrowth has finally been invited into political discussion, but it is still too often delegitimized and ridiculed. It’s about no longer growing just to consume more and more. Work fewer hours, buy less, travel less far, eat local…

Why is degrowth so caricatured?

Delegitimizing degrowth means that the policies in place are not called into question. We are talking about a total paradigm shift, inevitably, power clings and resists. However, the need to at least curb growth for ecological reasons has been studied for a long time. We can go back to the Club of Rome of 1972 (think tank bringing together scientists, economists, civil servants, industrialists from 52 countries) with Stop at the crossingeven ten years earlier with The silent spring (investigation by Rachel Carson, American biologist, on the ravages of pesticides). As the successive alerts have not been heard, have not given rise to serious implementation, the situation is worsening, with increasingly frequent extreme climatic events. By apprehending the phenomena separately, there is no questioning of the capitalist software that leads us to this global warming.

“This is an alternative project, not to growth, but to its mindless worship”

Alerts that have given nothing for decades so… How to explain it?

There are two reasons for this. First, what the philosopher Jean-Pierre Dupuy called: “enlightened catastrophism”. We know very well that we are going into a wall, but even knowing it, we don’t believe it, we refuse to believe it. When Jacques Chirac pronounced in 1992 his famous “Our house is burning but we are looking elsewhere”, he was the first to look elsewhere, we do not feel directly concerned.

Second, we are addicted to the growth system. Just like drug addicts, we know that we are destroying ourselves, but we refuse to undertake a cure. Our societies are consumerist and create an artificial need for dependence on surplus, especially with advertising. We are dissatisfied with what we have and we seek to satisfy our lack with what we do not yet have, but this is a false vision of happiness.

What is missing to change that?

These are deeds and facts. Some are convinced of the need to curb growth at the personal level, or even at the level of a group or collectives, but the passage to the act is lacking. Things have changed a lot over the past 20 or 30 years and there is a real rise in awareness – we can see it with the massive increase in the ecological vote in municipal elections, the place of ecology in speeches and in society, the proliferation of specialist stores like Biocoop, the reduction in meat consumption… But that is not enough.

This glass ceiling is explained in particular by policies which do not move much and which make a personal ecology, based on the consumption and the habits of the citizen. Everybody is made to feel guilty for not having closed the tap well, while during this time large groups like TotalEnergies are much more responsible for pollution and are not blamed or very little. Hitting the citizen is finally hitting the easy target and preserving the status quo.

This passage to the act, how to provoke it?

There are two motors to promote change: attraction, where it is not a question of saying that we are going to restrict ourselves, but that we would live better if we lived differently, and the pressure of necessity, in other words the good old kick in the ass that pushes us. For example, Chernobyl or Fukushima succeeded in persuading the Germans to phase out nuclear power. The real issue is this passage to the act, we must do everything so that it takes place even if it is not guaranteed that it will work, hence the title The wager of decline. It is a challenge, not a certainty of success.

“All societies in history except ours set limits”

Suppose we achieve a shrinking society, what would that look like?

The idea is to create a society of abundance, but without excess. Re-impose limits, as all societies in history have done except ours. There were three ways of imposing barriers: transcendence with religion and the deities, tradition and revelation with the prophets. However, since Les Lumières, it seems unbearable to us to see prohibitions imposed by mysterious powers. What modernity has irreversibly brought is that limits can only be defined collectively.

What could these collective measures look like?

The citizens’ convention is a good example of what should have been done and maintained, but it was not listened to. People are certainly not ready to sacrifice everything, but they can give up a lot as long as they understand why. This is the basis of democracy, we accept a decision if we recognize its merits.

During the coronavirus crisis, we accepted enormous deprivations, as during the first confinement which was extremely respected, because we found it justified. Just like during the mad cow crisis, people have changed their behavior in terms of food consumption, notably with a consensus to refuse the import of veal with hormones.

How do we create this change towards more collective decisions?

We must choose the politicians we elect for more education and more understanding. Next to us there is an example far from perfect, but more satisfactory: Switzerland, cantonal and federal, with a relatively democratic life compared to ours. So certainly, it is not because a decision is collective that it will be relevant, “We cannot prevent a people from committing suicide”, but precisely, if we screw up, it will be our own decision.

How do you respond to those who call you utopians?

They are the ones who are utopians, free trade is a utopia: entrusting its survival to imports from the other side of the world in a fragile and dependent system cannot work in the long term, they will see.