She was an impressive figure: blond, tall, her type was called “Junonian” at the time, which in no way meant excessive corpulence, she had a noble, clear, even face, she didn’t care about conventions, although or because she came from a noble family and married into a noble family. There are photos of her smoking a pipe. Once she was photographed with one of her beloved dachshunds for a passport photo – the dog had to be cut away because two people were not allowed to be shown in a passport photo. Your friend Karl Kraus called her “a woman who has more spirit than all German writers put together” (and written by a man who had previously not always emphasized the connection between woman and spirit). Another friend, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, spoke of her “passionate, almost disconcerting frankness”.

Mechtilde Lichnowsky (also Mechtild in early publications) bore her husband’s name, but she herself came from a by no means insignificant nobility, for she was a direct descendant of Empress Maria Theresa and a scion of the Arco-Zinneberg family. She grew up at Schönburg Castle in Upper Bavaria.

She enjoyed the kind of upbringing that was then given to the so-called higher daughters, but in many areas she excelled far above the average. She played the piano so well that she could recite Beethoven sonatas by heart, she later composed music for Karl Kraus for Nestroy Couplets, which he performed with great success, she drew and painted at a high level. Her caricatures and animal drawings are of high precision and considerable wit, and there is an oil portrait of the future husband, which Max Liebermann also painted – the wife can definitely keep up. She was not unknown as a writer in the period around the First World War and in the 1920s. Once you translate “uomo” as “man”, then Mechtilde Lichnowsky was a uomo universale.

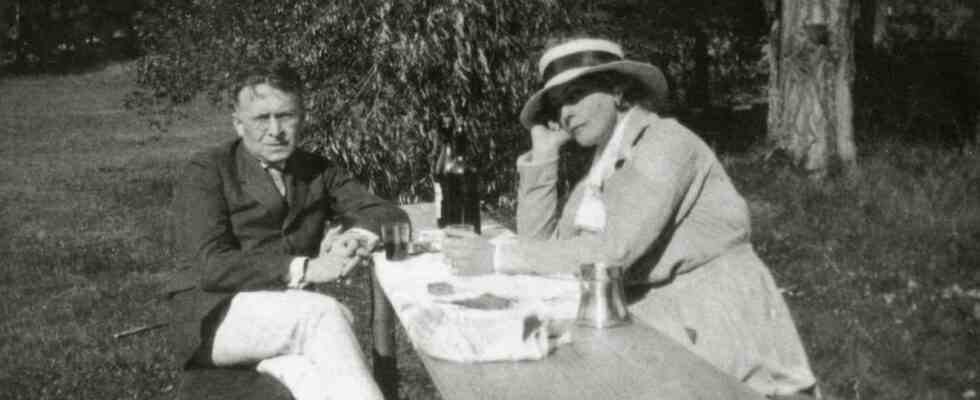

Friendship until the end of his life: Karl Kraus and Mechtilde Lichnowsky around 1930.

(Photo: Anonymous/picture-alliance/Imagno/Vienna City and State Library)

Her much older husband Karl Max Fürst Lichnowsky also came from an illustrious family. His ancestor Carl Lichnowsky had been a friend and major supporter of Beethoven. Karl Max was a diplomat and, after a checkered career, became German ambassador to England in 1912. It is a credit to his biography that in 1914 he was the only German diplomat in a senior post who used all the means at his disposal to warn of the war and also put this down in memoranda. That was the end of his diplomatic career.

Mechtilde Lichnowsky was a genius of friendship. She launched an appeal for donations the penniless Rainer Maria Rilke, still from London, which then became obsolete when war broke out, also because Ludwig Wittgenstein gave both Rilke and Georg Trakl a large sum. She also did a lot for Johannes R. Becher, who later became Minister of Culture in the GDR and was then a young aspiring poet endangered by an unstable personality. The childhood friend Wilhelm von Stauffenberg is less well known, but no less fascinating. First a lawyer, then a doctor, neurologist and psychoanalyst, he impressed many who met him, as Hofmannsthal, among others, testified. Physically handicapped, he died young.

And then of course Karl Kraus. Her rescue from the rapids of the Vltava, into which she had fallen while bathing, by the experienced swimmer Kraus, became famous and was the subject of literary themes by him and her. Their friendship, marked by spiritual agreement and personal sympathy, lasted, with brief lapses, until his death. In letters he addressed her as “Dear Princess!” on. He once wrote: “How I would like to give my worthy thanks for all the wealth that a heart and a head of rare connection offer”, and she dedicates her brilliant language-critical book “Words about Words”, on which she worked for many years before it then finally appeared in 1949, “in friendship with the then living Karl Kraus and today with the immortal one”.

Eva Menasse writes that Lichnowsky did not like to compare himself with intellectual men

With this text we are at the highly gratifying selection of their writings, which have just been edited competently and competently by Hiltrud and Günter Häntzschel, on behalf of the German Academy for Language and Poetry and the Wüstenrot Foundation, has appeared. It is the first edition of a collection, if not all, of Mechtilde Lichnowsky’s writings, just in time, one might say, before her name was entirely forgotten. Evidence of this situation is the fact that by the time this edition was published, only one title out of a total of 18 books was still available.

If you read the four volumes of this edition, which is as beautiful as it is welcome, you come closer to the phenomenon of why Mechtilde Lichnowsky, despite all the unmistakable, significant advantages of her writing, made the big breakthrough during her lifetime to become a successful author, like Vicki Baum, for example, failed. And even more so after the Second World War, when she lived in London again, she was no longer able to take part in German literary life.

Was she how Eva Menasse writes in her engaging introductory essay, really unsure in the end if she could compare herself to intellectual men? This can be doubted. More important may be that she obviously didn’t want to be a writer with a sharply defined branding and recognisability. The versatility of her talents is also reflected in her writing, and it may be this universality of her wisdom in life and language, combined with clear level requirements for herself and the readers, that prevented an even broader success at the time. It is to be hoped that things will look different today.

Mechtilde Lichnowsky: Works, 4 volumes. edited by Hiltrud and Günter Haentzschel. With an essay by Eva Menasse. Zsolnay, Vienna 2022. 1872 pages, 60 euros.

She makes her debut with a book about a trip to Egypt, she writes prose that was classified under the category “society novels”, she writes a thoroughly successful novel “An der Leine”, which attracts dog lovers because of its title (Lichnowsky is an animal lover in general and – descriptor of the first rank), but it is a novel not only about man and dog, but also about dog and man, about man and nature as a whole. Max Reinhardt performs a play by her.

“The fight with the expert” (the only text that is missing in this selection) is accompanied by a certain resonance, a satirical, highly witty examination of what is today called expert(in)culture. She writes just as impressively autobiographically about her childhood as she collects quotes from Hitler for her language-critical considerations, this “creature from Braunau, whose name never escapes my lips”, “a muddlehead of disconsolately sad celebrity”. In this way, her profound and entertaining book “Words About Words” can definitely be placed next to Victor Klemperer and Karl Kraus.

In the spirit of Kraus, including Wittgenstein’s, she writes: “If the thought is clear (something unclear can never be called ‘thought’), then it is also the language that expresses it.” In Wittgenstein’s “Tractatus” it says: “Everything that can be thought at all can be thought clearly. Everything that can be said can be said clearly” (it cannot be proven that Lichnowsky knew this text by Wittgenstein). Her highly developed feeling for language is reflected in her crystalline, nuanced, flexible style, her prose is often tinged with humor and satire, sometimes refreshingly malicious, not a single line of this author exudes bleakness or insipid solidity.

The four volumes of this beautiful edition (which also contains an unpublished novel from the estate) offer plenty of reason to be happy about the rediscovery, or rather rediscovery, of one of the great German writers.