Nine giant eyes stare at the visitor. Glucking cartoonishly cute, piercing you with eyelashes like lances. That’s a delicious irony in the spirit of its creator. Because visitors come here to see for themselves: works by Salvador Dalí. Of course, these eyes mean even more, mythological, psychoanalytic, spiritual, so everyone can sit down for a while on one of the 2,000 armchairs in the hall and rummage through their subconscious.

Apparently these nine eyes in a tent-like sheet landscape are a picture. And what a thing! An original painting, because Dalí painted it personally, as a photo hanging next to it shows with the artist and a two-meter-long brush. But they were also a prop, the backdrop for the famous dream sequence from Hitchcock’s 1945 psychological thriller “Spellbound” (in German: “I’m fighting for you”) with Ingrid Bergmann and Gregory Peck, in which a large pair of scissors are placed around the eyes snips. Now the canvas, stretched on two stretcher frames, measuring eleven by five meters in total, hangs as an eye-catcher and central masterpiece in a concert hall, the Philharmonie, which is being used here for the first time in a long time. The Oscar-nominated film music by Miklos Rozsa sounds, and more eye projections blink around from the brick walls. Eerily beautiful.

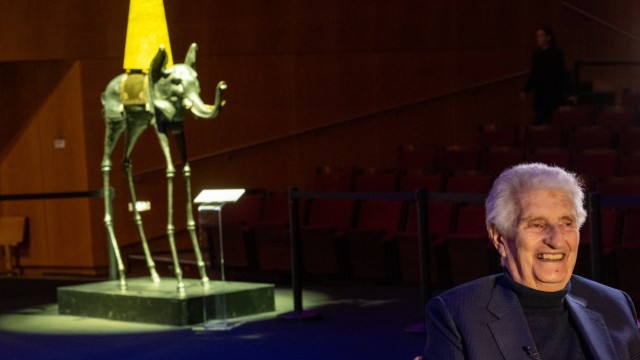

Beniamino Levi sits on the stage below – but only during the presentation for the media. He is the central figure of the “multisensory” Dalí exhibition at the Fat Cat (the Gasteig awaiting renovation). All the works here belong to the Italian gentleman, who celebrates his 96th birthday on Friday, February 2nd, the day of the opening. The art collector, gallery owner and operator of two Dalí museums in Paris and Bruges once also recovered the “Spellbound” set from the son of film producer David O. Selznick in the USA, he says. He has only shown the picture in Beijing, Shanghai and London, but never in such a huge space. He beams and is amazed: “This is new for me. It’s fantastic. It’s like a city.”

The highlight of the exhibition: Dalí’s monumental picture for the Hitchcock film is staged in the Philharmonie.

(Photo: Catherina Hess)

So my Levi also saw the entire Dalí show, an art exhibition that has never existed before. Like the immersive projection events on Frida Kahlo, Klimt, Monet (and now a total of 20 from New York to Vienna), it is an invention of the Allegria agency, and therefore from München-Musik. “But this is different,” says Nepomuk Schessl, who had the idea: “Here we are combining the digital with the originals for the first time.”

The sculpture of a decomposing clock on the square in front of the Gasteig weighs 2.8 tons – and is an original.

(Photo: Catherina Hess)

The Dali show in the former Philharmonic Hall can be visited until April 21st.

(Photo: Catherina Hess)

Original and Dalí – that’s always one thing. There are tens of thousands of counterfeits circulating on the market. The master was flattered by this; he himself is said to have added his autograph to 40,000 blank sheets for lithographs. There are millions of licensed prints, there is mass kitsch for the home shelf – here in the foyer you can also buy Dalí motifs on puzzles, magnets and socks, melting clocks as bookends (38 euros) and original bronzes limited to twelve pieces (to “talk about it “we don’t” price). A completely normal exploitation chain, just like the world star artist himself once did.

All of the works shown in the show, such as this elephant sculpture with obelisk, belong to the art collector and gallery owner Beniamino Levi.

(Photo: Catherina Hess)

So what is real? Everything from Levi, who is an original himself. The gallery owner first met Dalí for two minutes (“only he talked”) in a Paris hotel, and on the way out the secretary offered him two small bronzes. One of them, “Hommage à Newton” from 1968, a gold-plated figure with an angular hole in the stomach and a pendulum, stands here in a display case next to a funny man stuck in car tires (“The Michelin Slave”). Levi is considered the world’s leading expert on Dalí sculptures and himself – “they were initially more affordable than the paintings” – bought many at auctions and commissioned them from the artist. “His wife often mediated – he was quite difficult.” There are museum pieces such as the finely painted “Surrealist Eyes” stacked to form a skyscraper-like tower. There is something monumental: the 2.7 ton pocket watch on the forecourt; and the four meter high, yet fragile “Rinocerus cosmique”, which had to be maneuvered in with a special crane.

The rhino sculpture is over four meters high and had to be brought in with a special crane.

(Photo: Catherina Hess)

A dancer-piano creature, an elephant with a yellow obelisk, Mae West’s lips as a sofa – these are pieces to amaze. On the other hand, delicately touching: Dalí’s pencil sketches for “Spellbound”, or his Picasso-like ink drawings for the never realized film “Babaouo” (1974).

Due to the creative phase from late Surrealism through the paranoid-critical method to the “Classical Period”, this is far more than just the photorealistic art kitsch that is familiar from the walls of some dentist’s offices. For the Frenchman Nicolas Descharnes – the son of Dalí’s managing director Robert is also present as an original and connoisseur – the iconic artist with the twirly beard is still the “King of the Surrealists”: highly intelligent, a continuator of Renaissance art, creator of his own mythology .

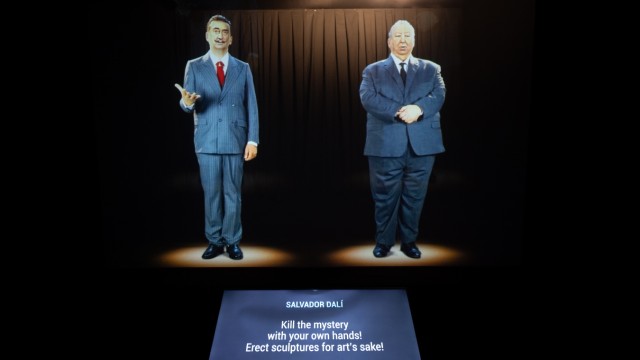

As holograms, Salvador Dali and Alfred Hitchcock talk to each other about art.

(Photo: Catherina Hess)

Seen from the outside, the metaverse is just a room – but through the computer glasses, visitors imagine themselves in the indistinct expanse of Dali’s world of images.

(Photo: Catherina Hess)

A single show could never capture the complexity of the multi-talented artist. “Dalí – Spellbound” doesn’t even try to do that. Based on her “hero piece” (Schessl), she has a theme: How did Dalí and Hitchcock influence each other? The two creative geniuses who are friends even talk to each other as holograms. Hitchcock hired Dalí for the “vividness of his dreams,” the “long perspectives,” and “sharp shadows,” as he said: “It was the avoidance of a cliché: all dreams in films are blurry.” From the psychoanalysis scene with Peck and Bergmann, the exhibition continues with nightmares, shame and religion (a twisted Christ cross), with originals, a great children’s sand play corner, video installations, a mirror room and, at the highlight, the Hall of Eyes.

Nicolas Descharnes, the son of Dali’s private secretary Robert Descharnes, in front of a bronze cross.

(Photo: Catherina Hess)

If you don’t have to go to your psychiatrist quickly, you can still get shaken up in the “metaverse”. This is a virtual reality course that you feel your way through with computer glasses: From Freud’s treatment room (“Anyone who dreams of eyes feels like their privacy has been violated…”), portals lead to seemingly endless worlds of images, an ocean flying whales, a desert with elephants, a memory full of eyes. A technically generated, walk-in, interactive dream, artificial, and yet so real that one often stumbles, doubts, dibs. “I was really shocked when I had to go through that door made of fire,” says Levi, and is happy: “If Dalí were here, he would be very happy.” Descharnes also thinks: “This is the best we can do with our resources.” But would Dalí, who himself experimented with holograms and designed crazy museums, have done it that way? Nobody could know that, that’s exactly what made his genius: “Maybe he would have had a really crazy idea that would have blown us all away.”

Dalí – Spellbound – The exhibition, extended until May 19th, Munich, Fat Cat / Gasteig, Philharmonie, www.alegria-exhibition.de