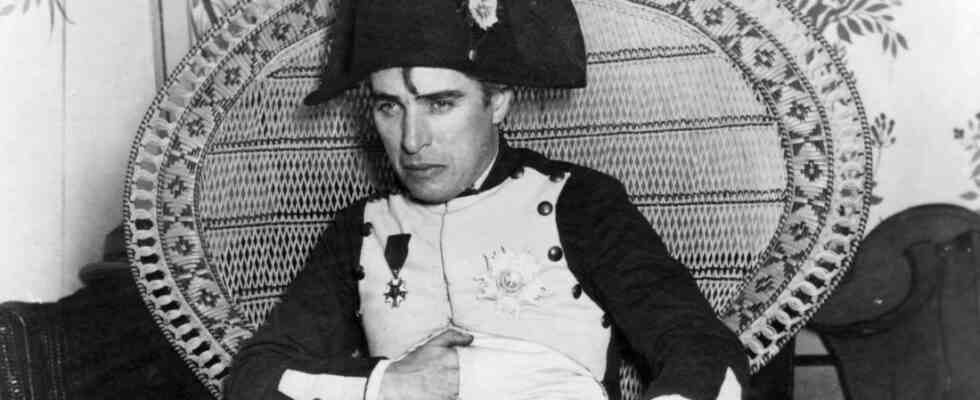

Every actor has a desire to play Napoleon, Charles Chaplin was convinced of it – that man with the hand tucked into his waistcoat, the dark sad eyes so much more fascinating than Christ’s. His father, Charlie’s mother used to say, looked like Napoleon. When Chaplin in the twenties, world famous and very rich through his slapstick comedies, was looking for new, not necessarily funny film material for the women at his side, in 1922 he worked on a story about Josephine, Napoleon’s wife, for his then partner Edna Purviance . He then abandoned the project and compensated Purviance in 1923 with the melodrama “A Woman of Paris”. In 1926 he appeared as Napoleon at one of Marion Davies’ legendary costume parties, with his new wife Lita Gray as Josephine at his side.

Napoleon was a big hit in the cinema. Marlon Brando and Rod Steiger, two seasoned method actors, worked hard on the role. And great filmmakers put a lot of work into their Napoleonic visions. Stanley Kubrick amassed mountains of material for a monumental (never made) film. Francis Coppola financed the reconstruction of Abel Gance’s 1927 five-and-a-half hour “Napoléon”, including new music by his father. Ridley Scott is finishing his Napoleon film, starring Joaquín Phoenix.

In London he met a prominent supporter of the project: Winston Churchill

Throughout the 1930s, Chaplin had also been working on a Napoleon film. The history of this project is well documented in the great Chaplin biography by David Robinson, 1985 and in the book “Chaplin’s War Trilogy” by Wes D. Gehring. There is also a featurette by Cecilia Cenciarelli, “Chaplin’s Napoleon and The Great Dictator”, to see on youtube. None of them can pinpoint why Chaplin dropped the project, but it is evident that some of this work went into the 1940 film Chaplin dedicated to another tyrant character, Adolf Hitler in The Great Dictator.

In this film Chaplin plays a double role, a small Jewish barber and the dictator Adenoid Hynkel, in the end the barber is mistaken for the fierce ruler and delivers a flaming speech for freedom and peace. In the case of Napoleon, too, there was a double, highly attractive to Chaplin, whom the British exiled instead of Napoleon.

Unlike his American slapstick colleagues, Chaplin was very interested in politics, business and science. After his film “City Lights” he embarked on a sixteen-month world tour, meeting many politicians and scientists in Europe, from Einstein to HG Wells. In France he was referred to the novel “La vie secrète de Napoléon Premier” by Pierre Weber – and his brother Sydney was immediately enthusiastic about the project: a dramatic film with Charlie! And one in which he spoke for the first time! Another advocate for the project Chaplin met in London, who was a keen collector of Napoleonic books and memorabilia, was Winston Churchill. “You must do it!” he implored Chaplin.

The film should have a strong pacifist message

Back in Hollywood in the summer of 1934, Chaplin wrote a Napoleon script with the young Briton Alistair Cooke – which has not survived, it was not filmed. In early 1936 another Napoleon Script was completed, together with John Strachey, a great young English left-wing intellectual. The double motif was very strong here, as was the pacifist and humanist message (which then became dominant in “The Great Dictator”), and there was also a nice role for the partner Paulette Goddard, who had already played in “Modern Times”.

David Robinson quotes phrases from the script that make Napoleon a visionary of the 20th century: “There is something wrong with the whole political structure of Europe… Governments and constitutions are antiquated, obsolete… I mean, the time of wars and the aggression is gone once and for all… One can achieve more through treaties, friendship, commercial understanding… If I could live my life again, I would use the power of my victories to unite all the countries of Europe into one compact state to unite …”

As for the comic aspect of Napoleon, Chaplin later made some comments: “Well, Napoleon had a double. And the British sent this double to Elba and to St. Helena. The real Napoleon, on the other hand, lived quietly in Paris, had a bookstall at Pont de l’Alma He became a pacifist and gave his earnings to the widows and children of war veterans… When Napoleon’s double died, the body was brought back by the British Navy and given to the French for burial… All Paris flocked to the Streets… It’s a big crowd scene, with this scene I open the film… The real Napoleon is busy as always with his bookstall, business is particularly good that day As the funeral ship sails slowly down the Seine – a pan in a close-up of him – he mumbles: The news of my death is killing me.”

The destructive potential brings slapstick and dictatorship together in a disturbingly grotesque way. How the great dictator Hynkel played with the world until his globe bursts has a perverse elegance, but you can’t imagine it with a character like Napoleon. And as for the desire to embody Napoleon, Chaplin said after his “Great Dictator”: “I’ve gotten rid of it, I’ve now played Napoleon and Hitler and the mad Tsar Paul, all rolled into one.”