Status: 07.01.2022 4:17 a.m.

For decades, indigenous children in Kanda were snatched from their families of origin and subjected to abuse in the school system. Now the state pays compensation to 115,000 children and young people.

Ashley Bach had just been born when she was taken from her mother. The girl from an indigenous community in the north of the Canadian province of Ontario grew up with foster parents in British Columbia. “When my biological parents wanted to take me home, they forbade me,” she says. In the reservation in which they live, the conditions are too bad.

At 18, she left the – as she says – “hostile atmosphere” of her foster family. Since then, the now 27-year-old has been fighting for the suffering that was inflicted on her and more than 100,000 other children to be recognized and compensated. With success: the Canadian government has now promised 40 billion Canadian dollars – the equivalent of around 28 billion euros in compensation. “This compensation will enable those affected to attend to their needs and reconnect with their indigenous groups. Not only to survive, but to get ahead in life,” she says.

“Recognize collective responsibility”

Ashley has already done it: She went to university and was instrumental in the agreement that the Canadian government reached after long negotiations with victims’ associations. A milestone, says Canadian Prime Minister Trudeau: “For far too long, indigenous children have been torn from their families and groups. They have lost their language and their culture, they have been mistreated. We have to recognize our collective responsibility for this.”

The “historic agreement” is about ending this injustice. It stipulates that all around 115,000 indigenous children who were snatched from their families between 1991 and 2021 should receive at least $ 40,000. In total, more than 200,000 children and their families should benefit from payments.

In addition, the home and social system is to be reformed in the long term with 20 billion dollars. Cindy Woodhouse, who represents the indigenous communities in the Canadian province of Manitoba, believes that there is an urgent need: “The entire youth welfare system in Canada was wrong from the start. Many do not know that, but there were incentives to take indigenous children out of their families. The local authorities got money when they put children in foster families or homes. “

Compulsory adjustment in “residential schools”

One explanation for the fact that less than eight percent of children in Canada come from indigenous families, but that they are completely overrepresented in foster families and institutions at 52 percent. “There is still a long way to go,” said Woodhouse. “No amount is sufficient to combat the suffering and poverty of the indigenous population. Money cannot make up for the loss of a child either. But it is about recognizing suffering and making sure that it is seen and heard.”

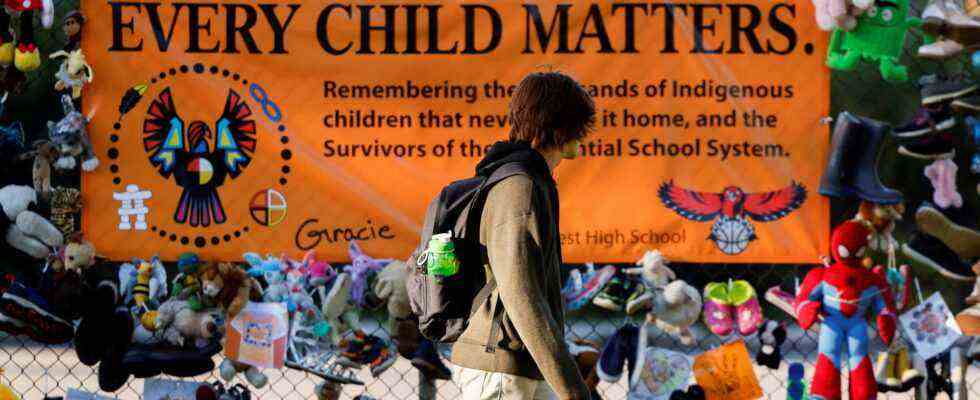

This is what the indigenous families who are affected by the system of so-called residential schools want: Between 1830 and 1996 around 150,000 children of indigenous people were separated from their families and put in boarding schools in order to force them to adapt. Many of them were ill-treated and subjected to sexual violence there.

The discovery of more than 1,000 graves caused horror beyond the borders of Canada in the past year. Lots Indigenous communities blame the homes that have shaped entire generations for social problems such as alcoholism, domestic violence and increased suicide rates. UN human rights experts have requested full clarification from the Canadian government and the Catholic Church, which operates many of these homes.