In Colombo’s Viharamahadevi Park, the heat is oppressive, a few walkers lie motionless on the parched lawn, only the ubiquitous chipmunks chase up the cinnamon trees. Still, the handful of sweating listeners on the porch of a weather-beaten pavilion listen intently as Kumari Kumaragamagage explains what poetry means to her. “Don’t put me in a cage. I am an ocean, I am the sky”.

The art festival is intended to protect civil society

The poet and women’s activist, snow-white hair and baggy blue pants, was one of the artists that Dora García invited to open-air readings. “Hearing Voices” the Spanish installation artist had her open-air recitation forum for the seventh Colomboscope Festival baptized, which took place in Sri Lanka’s capital at the end of January. The arts festival emerged as one of the many initiatives with which protagonists from civil society wanted to permanently secure the “freedom of expression” that had been crushed by the civil war between Sinhalese and Tamils between 1983 and 2009.

A “Colombo Biennale” founded in 2009 by the British gallery owner Annoushka Hempel did not last long. The annual Colomboscope Festival, founded in 2013 with the help of the Goethe-Institut, the Alliance Francaise and the British Council, has survived to this day. It is now the largest contemporary art event in the 23 million island nation in the Indian Ocean.

“I liked the interdisciplinary format, I fell in love with the island,” Natasha Ginwala, an art historian of Indian origin, explains why she ended up staying after curating the festival for the first time in 2015. Now she is its director, commuting between Colombo and Berlin, where she works as a curator at the Gropius-Bau, drawing from the aesthetic pool of two hemispheres. In 2014 she was part of the team for Adam Szymczyk’s documenta 14. In 2018 her course on Indian modernism received recognition, which she contributed to “Hello World”, the project with which Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof subjected its collection to a critical revision.

Sri Lanka is a Socialist Republic. According to observers, the ruling brothers, Gotabaya and Mahinda Rajapaksa, one president and the other prime minister, are maneuvering the country in the direction of Buddhist fascism. Just as she tries to please the radical Buddhist movement Bodu Bala Sena, the “Buddhist Armed Forces”.

Natasha Ginwala directs the Colomboscope Festival in Sri Lanka. She is a curator at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin and was a consultant for Documenta 14.

(Photo: Socher/ Eibner-Pressefoto/imago/Eibner)

Covid incidences are low, yet the country faces famine. Due to a lack of foreign currency, it has to pay for its oil from Iran with tea. The images of the Islamist attack on Easter Sunday 2019 are still impregnating the collective consciousness.

Finds and files are reminiscent of those who disappeared during the civil war

So it’s a miracle that Ginwala and her co-curator Anushka Rajendran were still able to bring out the show with 50 international artists, which was canceled in 2021 due to the pandemic. Also Colomboscope follows that critty-polity-Mainstream of international biennials. In Sri Lanka, this well-known mixture of anti-militarism, queer policies and feminism still means something. Because the works presented opened up a space for the problems that politicians on the island buried under silence.

The artist Imaad Majeed pushed the festival’s commemorative impetus in the small printing museum W Silva with his “Testimony of the disappeared” room: personal finds and official files recall the fates of those who disappeared in the civil war. MTF Rukshana showed how poetically political concerns can be expressed. Her torn pieces of weaving address the wounds and fractures that matrimonial and family law in Sri Lanka, which has not changed since 1951, burdens women in particular when they want to get a divorce.

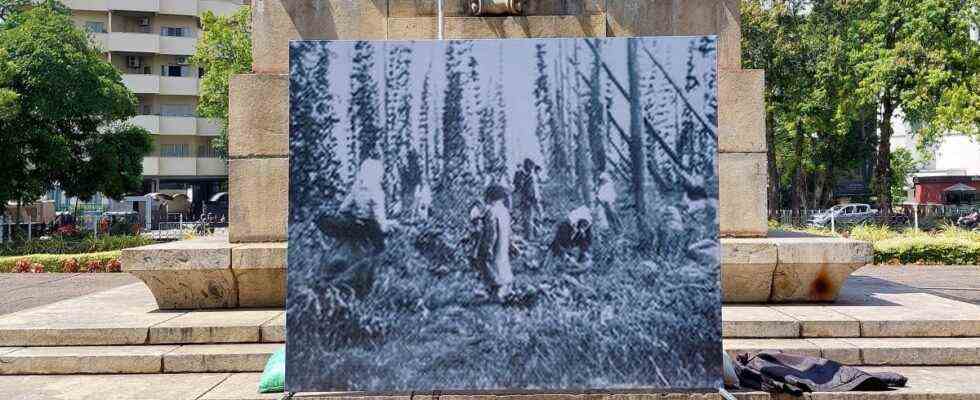

Dora García built a kiosk for readings in Colombo’s Viharamahadevi Park.

(Photo: Ingo Arend)

The pronounced political problem awareness of the festival in the Rio complex became obvious. Opened in 1965 as one of the first cinemas on the Slave Island district, formerly inhabited by black slaves from the Portuguese and Dutch colonists, it went up in flames during an anti-Tamil pogrom in 1983. Colombo’s cultural scene has rediscovered the charred ruins of grandiose desolation.

The view of the Lotus Tower goes out of their shattered windows. The green TV phallus, stretched 350 meters high, ends in a violet shimmering flower at the top – a symbol of dreams of the international financial metropolis that Colombo is just burying again under the pressure of the crisis. Colomboscope manages without any hint of cinnamon and lotus clichés, which westerners who are weary of civilization like to project onto the “tears of India”. Instead, with artists from Lebanon to Malaysia to New Zealand, Ginwala developed the festival into a bridgehead for the young, politically alert South.

On the neighboring subcontinent, the biennials in Karachi, Kochi and Kathmandu always operate in the shadow of its political tensions. Sri Lanka is – still – a kind safe space, an intercultural crossroads of the most diverse positions, far removed from the usual suspects of the Western art scene. Here Lavkant Chaudhary, whose drawings on strips of parchment in the Public Library commemorated the oppressed Tharu minority in his native Nepal, met Haziz Azara.

Art, theatre, literature and politics enter into a symbiosis

In his fascinating video “Takbir”, the Afghan artist projected footage from Kabul, which had just been conquered by the Taliban, onto one of the rotten walls of the Rio complex – a symbol of the night as an experience of terror, but also a refuge. And when the cultural anthropologist Omar Kasmani read from an essay about his experiences as a queer Pakistani in Berlin in the Lakmahal district library, which acts as a reading room, on a wooden divan modeled after Sufi furniture by the artist group Slavs and Tatars, this year’s motto ” Language is migrant” suddenly clear. Ginwala and Rajendran borrowed it from a poem by the Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña. Colomboscope is the amazing example of transformation. Ginwala freed it from the influence of the sponsors from the beginning, cooperated with initiatives from all over Sri Lanka, sharpened the political approach.

This year, too, the curators mixed experimental formats: a neighborhood walk to scenes from the civil war, dance performances in a gay cruising cinema or a rap and poetry slam in a workers’ bar on the outskirts with the classic art course. Is it because of the eternal sun on the island or the gentle, unpretentious nature of the curators? There was never the feeling of completing a crash course critical of capitalism, but of moving in a delicately spun cosmos in which art, theatre, literature and politics enter into a natural symbiosis. There are a number of biennials and events coming up in Europe this year: perhaps a new mode of art presentation could look like this – beyond Venice, Kassel or Berlin.