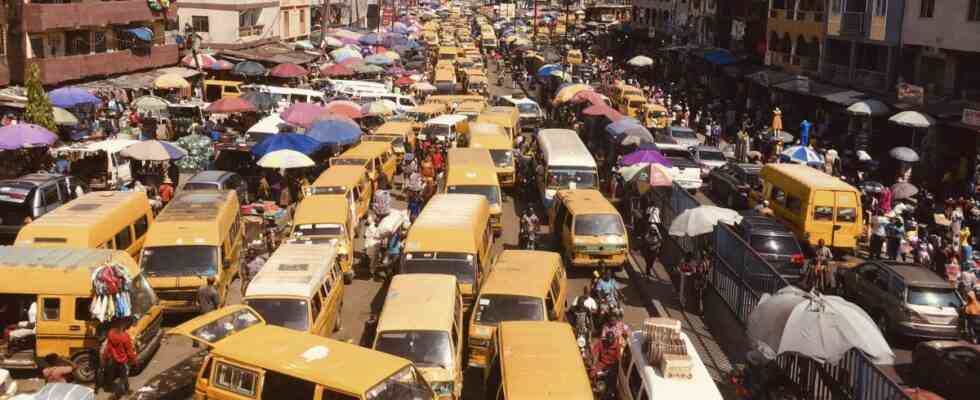

The chaos appears murderous, in fact it probably is. Every day, an endless line of battered yellow private Danfo minibuses plows through Lagos, Nigeria’s capital and one of the largest metropolitan areas in the world with a population of over 14 million. Trend: further strong growth. In terms of congestion, Lagos is likely to be moving towards one of the top urban locations, with people leaving their homes here as early as four in the morning in order to get to the office on time. Working public transport? Nothing, which is why Lagos’ former governor doesn’t see a “real megacity” in his metropolis, “as long as these yellow buses are on Lagos’ streets”.

“Order is fundamental anti-urban”, on the other hand, Ben Wilson writes in his famous book about metropolises and then explains over the next 500 pages what led him to this view, which is a mnemonic phrase that every building authority, every member of the urban planning guild and other urban thinkers would like to share because one of the greatest evils of today’s cities is the overbearing megalomania of their planners, whereby the masculine is deliberately chosen here, for a long time there were hardly any women in this discipline, one could also say non-existent.

Ben Wilson, born in London in 1980, is a historian and lives in Suffolk.

(Photo: Natasha Moreno-Roberts)

But in his “World History of Mankind in the Cities” Wilson is not concerned with architectural master plans and their creators, he is concerned with what kind of life metropolises have made possible over the millennia, i.e. he is concerned with what lies between stone , wood, concrete and steel. And that’s exactly why you’re so happy about the book and wish it many readers. Because the city is far from recovering from the two-year pandemic, as Corona took away almost everything that had made it attractive to date. The attraction of metropolises was immediately reversed with the epidemic, as density, crowds of people and contacts with countless strangers suddenly meant the greatest danger.

Uruk, the first city in the world, was founded in Mesopotamia in 4000 BC and had up to 80,000 inhabitants.

(Photo: ESSAM AL-SUDANI/AFP)

That’s where Wilson’s “Metropolis” comes in handy, because the British author and journalist makes it clear in a clever but entertaining way why our species cannot do without the urban way of life: “The concentration of human brains in a small space is the best way to generate ideas to fuel art and social change.” The historian can quickly dispel the fear that his declaration of love for the city may have been a bit too coarse-grained. Firstly, because it really plods its way chronologically through the millennia, from Uruk, the first city in the world, to the megacities of the present, without ignoring the dark side. And secondly, because he repeatedly breaks this chronology and draws parallels through the millennia, from medieval Baghdad to modern-day London, from ancient Rome to megacity Tokyo, from present-day Singapore back to cosmopolitan 11th-century Palembang.

Even if every metropolis is individual, something like an urban essence can be identified

It is astonishing how many points of contact there are for this type of urban historiography, for this urban ping-pong between the centuries. For example, because it becomes visible how climate changes have always influenced cities by ensuring that metropolises have settled in one place or had to be abandoned. The climate catastrophe today is likely to increase the impact on cities even further. Or because pandemics such as the “Black Death”, i.e. the plague, always hit cities hardest, which Corona has once again drastically demonstrated, but after that the living conditions in metropolises were often improved, for example because the sewage system was modernized . Or how cities stimulated innovative power from the very beginning, Uruk already ensured the invention of the wheel, loom and cuneiform writing. And of course, because the urban promise par excellence – for prosperity and a better life – has consistently driven people into metropolises up to the present day when – at least according to statistics – 200,000 people move to cities every day.

Ben Wilson: Metropolises. The world history of mankind in the cities. Translated from the English by Irmengard Gabler, S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt 2022, 592 pages, 34 euros.

(Photo: S. Fischer)

Even if every metropolis is individual, something like an urban essence can be determined. Shakespeare already knew that Wilson could carve this out of history by taking a closer look at the lives of the people there, when he wrote “What is the city but the people?”. But it is precisely this perspective that makes the book so entertaining for the reader, because Wilson not only analyzes urban culture, from Dutch genre painting to Compton gangsta rap. But he also devotes himself above all to everyday life in cities, looks at swimming pools, cafés and street vendors for their importance, goes to markets, department stores and red-light districts. “For much of history, urban life has revolved around the sensual: food and drink, sex and shopping, gossip and games.”

It is interesting how differently the West compared to other societies has viewed the city throughout history: “Western Europeans and Americans have an inherited antipathy to city life that is absent in many other cultures. There, urban life is embraced more readily. In Mesopotamian societies, in Mesoamerica, China and Southeast Asia, the city has always been considered sacred, a gift from the gods to humanity. In the Judeo-Christian world view, however, cities are in contradiction to God and are at best a necessary evil.” The urban species has not only been found in the East since China’s massive wave of urbanization. “Throughout the Middle Ages, nineteen of the twenty largest cities in the world were either Muslim or in Imperial China.” In terms of technology and hygiene, but also global trade, the metropolises there were far superior to those in Europe. But nothing helped, as Wilson’s chapter on warlike Lübeck or Lisbon makes clear, whose history is that of a cosmopolitan city “which wrestles down its rivals and eats its corpses to fat”. Anyone who has ever been to the Coach Museum in Lisbon knows how magnificent this gluttony at the expense of others can look.

“The scurvy European sailors, with their measly cargo of worthless trinkets, had little to offer this sophisticated, poly-ethnic urban world that traded the riches of Asia and Africa. What they did bring with them, instead, was an aggressive, hateful anti-everything bias Muslims they had learned in the grueling Crusades in Morocco and Tunisia.” Which shows that the rise of the European city type began “in the ruins of Tenochtitlan, Calicut, Mombasa, Malacca and other cities”.

Which means nothing other than: the history of cities is always the history of world politics. And since the future of mankind will be decided in the metropolises for better or worse, it makes double sense to know their past.