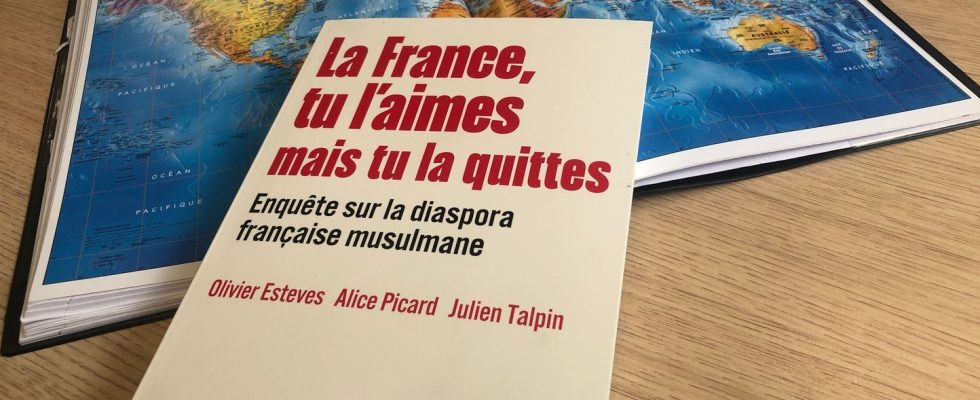

Islamophobia in question. The book France, you love it but you are leaving it*, released this Friday in bookstores, puts its finger on a phenomenon that has until now been kept silent. For two years, three academics, Alice Picard, Olivier Esteves and Julien Talpin, investigated the “silent flight” of France’s Muslim elite, a diaspora that escapes our country’s radar.

Their study is based on more than 1,000 testimonies from people born and raised in France, but who, one day, chose to leave. Almost always death in the soul. All are of the Muslim faith, whether their names are Smaïl, Karim, Khalid, Nouria or even Emeline. If they left, most of the time, it is so that we “leave them peace with their religion”, popularizes one of the co-authors, Olivier Esteves, professor specializing in the English-speaking world at the University of Lille.

“Atmospheric Islamophobia”

Thus, two main motivations emerge from this sociological survey to justify the departure: 71% of those questioned mention “racism and discrimination” and 63% spontaneously put forward the “difficulty of living their religion peacefully”.

For Alice Picard, co-author and researcher, it is an “atmospheric Islamophobia”. “Even if the results should be taken with a grain of salt, we can speak of anti-Arab racism, as it is generalized, to the extent that this minority should remain in its place. We have the impression that it is when these people access the social elevator that they face the most discrimination. »

This is the case of Driss**, based in Montreal, Canada. “Here, it’s a bit like the American mentality,” he explains to 20 minutes. As long as you bring in money, no one cares, you can display your religion without embarrassment. » Implied, this was not the case in France.

Because Driss maintains a little resentment towards the territorial civil service where he started to work. “Despite my level of studies, I quickly understood that I would remain stuck at a certain level,” he assures. I wasn’t discriminated against, but I had constant comments about my origins. »

“I always felt a suspicious look”

Third generation of an Algerian family, he is not “the type to leave a meeting to go and pray”, but he practices Ramadan. “Faith is something intimate. » In 2020, just with Covid-19, he decided to emigrate to Canada and does not regret it. “I work in IT with big responsibilities. In France, this would never have been possible, not even in a dream. »

With a hijab (an outfit that covers the head) on her head, Laura remembers: “I converted at the age of 17 in high school, just before entering university.” Joined by 20 minutes, she recounts her parents’ fears. “It was the time when many went to wage jihad in Syria. »

The young girl, who now lives in London, then moved into teaching. “During an internship for my master’s degree, the director of an association made me understand that I would not be able to keep my veil during the internship,” she says. I did not understand this ban because my mission was to teach French to a migrant public, some of whom wore the veil. »

Showing one’s religion has always been problematic for this young woman, now 27 years old. “I always felt a suspicious look, especially since it was seen that I was not North African,” she continues. Since she teaches in a school in London, wearing the veil goes unnoticed. “The right to indifference,” she explains. Some wear crosses, others the yarmulke. Here, the management provides a multi-faith prayer room. »

Questionable investigation method?

The three authors have collected hundreds of testimonies like these. “We have put our finger on a reality which is difficult to quantify because there are no official figures”, nevertheless recognizes Olivier Esteves.

The method of investigation could even be contested. “It’s true that there is a selection bias because we launched our call for witnesses on Mediapart,” he admits. But we were surprised by the enthusiasm generated by this unprecedented survey in France. It’s up to others to take it up to do a more in-depth study. »

The revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 had, in its time, caused an acceleration of the exile of around 200,000 Protestants from the kingdom of France. Many belonged to the intellectual elite and this brain drain had strengthened France’s economic competitors. Today, no French law discriminates against a particular religion.

However, many people interviewed highlight a heavy climate such as the debates on the veil or the abaya. “As soon as there is an attack, this population must give, more than others, proof of allegiance to the Republic and secularism,” specifies Alice Picard.

Coming from the same working-class neighborhood of Tourcoing, in the North, Laura and Driss claim to have experienced the same “tearing out” of leaving their loved ones and their country. “During the World Cup final in 2022, I came out with the French flag on my shoulders to support the French team,” says Driss. It’s my country. »

* 306 pages, 23 euros, Editions Seuil.

**Assumed first names.