Mark Spitz, Heide Rosendahl, Klaus Wolfermann – anyone who hears these athletes’ names immediately thinks of the Olympic Games in Munich. However, most of the athletes from back then have been forgotten or are not necessarily associated with Munich 1972. For example Uli Hoeneß. Only a few know that the former president of FC Bayern took part in the Olympics as a young footballer.

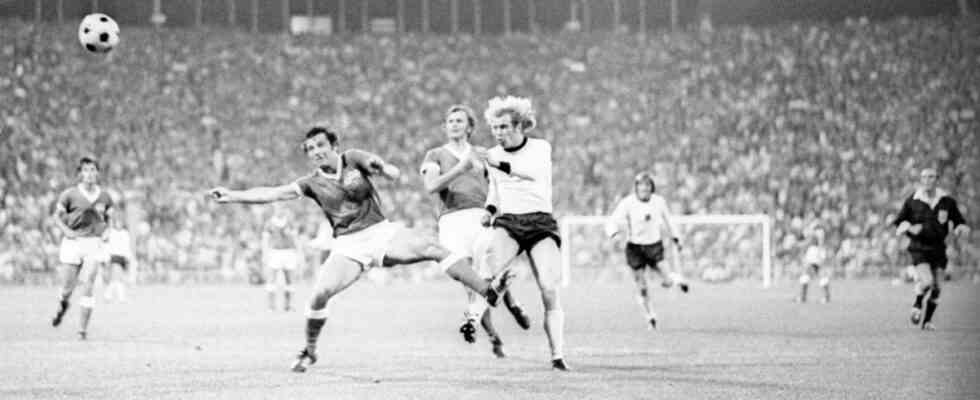

Film recordings show, however, that Hoeneß could hardly be stopped on September 8, 1972 in the Munich Olympic Stadium. In front of 80,000 spectators, he even scored the “Goal of the Month” with a spectacular scissors shot. Despite this, the West German Olympic selection lost 2:3 to the East German team that Friday and were eliminated from the tournament.

When the journalist Eberhard Stanjek commented on this game years later on Bayerischer Rundfunk television, he remarked that the argument was allegedly not entirely fair, because the GDR had started with their best players. Of course, this is how all teams from the Eastern bloc acted at that time. Professionals, said Stanjek, “didn’t exist in the socialism of the time, the West German team, on the other hand, was an amateur team”. Stanjek rightly questioned both statements.

Of course, the so-called state amateurs from the East were basically all professional athletes. The fact that the German selection should have consisted of nothing but amateurs was only true on paper. The 20-year-old Uli Hoeneß belonged to the FC Bayern squad in 1972, with whom he had just become German champion and with the German selection even European champion.

Even an Olympic amateur like Uli Hoeneß gets huge sums of money – secretly, of course

In order for him to compete in the Olympics, he just wasn’t allowed to sign a professional contract beforehand. Franz Beckenbauer’s statement is often rumored that Hoeneß was officially employed as a gardener at Bayern Munich. At the time, Dieter Kürten asked in the ZDF sports studio whether that was true. Hoeneß rejected a gardening job and said he was a normal employee. He only signed a well-paid professional contract after the Olympics.

In his biography of Gerd Müller, the historian Hans Woller reveals that even amateur players did not live badly back then. FC Bayern played many friendlies at home and abroad in the early 1970s. Manager Robert Schwan collected the fees in cash, but did not post them. The majority of this hidden revenue went directly to the players, according to Woller. Schwan usually paid out the money on the plane. Franz Beckenbauer later confessed that they returned with thick bundles. The DFB was not allowed to know anything about it. Even Olympic amateurs like Uli Hoeneß and Edgar Schneider, who shouldn’t have received anything from the club, received huge sums in this way, as the then FC Bayern President Wilhelm Neudecker wrote in his memoirs.

Classic amateur: The Swedish sports shooter Ragnar Skanåker, a six-time Olympic participant and the first gold winner in Munich, always earned his living as a gas station attendant.

(Photo: Imago)

As a rule, western top athletes were still employed in 1972. According to the regulations, only amateurs were allowed to start at the Olympics, i.e. people who did not make a living from sport. For example, the first Olympic champion in Munich, Swedish marksman Ragnar Skanåker, ran a gas station. And Frenchman Michel Carrega, silver medalist in trap shooting, continued his life as a coral fisherman in Corsica after his success in Munich. Irrespective of this, the idea of an Olympic amateur was already being circumvented in 1972, even outside of football.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) has maintained a tight watch over amateur status since the first modern Olympic Games in 1896. Even small transgressions were punished rigorously. The Cologne sports historian Stephan Wassong remembers the American Jim Thorpe, who won the pentathlon and decathlon in Stockholm in 1912. “But he was stripped of his gold medals because it was discovered that he played baseball semi-professionally,” says Wassong. Thorpe had only gotten a few dollars for it. The ban also hit the Finnish miracle runner Paavo Nurmi, who had accepted small expenses in 1930. In 1932 he was banned for life.

Karl Schranz becomes one of the last victims of the outdated amateur idea

Austrian ski racer and folk hero Karl Schranz was disqualified from the 1972 Sapporo Winter Olympics for wearing a T-shirt advertising a coffee brand to a charity soccer game. From the point of view of the then IOC President Avery Brundage, this was a gross violation of the idea of an amateur. Today, Schranz owns a hotel in St. Anton am Arlberg, whose website explains the consequences: “With his exclusion from the 1972 Winter Olympics in Sapporo, Karl Schranz fell victim to an outdated amateur law – and at the same time paved the way for the modern Olympic Games.”

The amateur rule that brought Schranz down was undermined six months later in Munich by the American swimmer Mark Spitz. With seven gold medals, Spitz was the superstar of the 1972 Games. At an awards ceremony, he waved his trainers at the crowd, a publicity-boosting move that violated Olympic rules and prompted the Soviets to immediately call for the American’s expulsion. Unlike in the Schranz case, IOC President Avery Brundage shied away from this step, which would have provoked a huge outcry. Other athletes immediately tested the limits. The Swede Gunnar Larsson, Olympic medley champion, also liked “the presentation of branded goods from the Olympic country,” according to the magazine The mirror remarked smugly.

Ulrike Meyfarth gets in trouble because of an advertising sign in a hairdressing salon

The Munich historian Ferdinand Kramer says that the exclusive admission of amateurs in 1972 contradicted the actual situation. More and more athletes maintained the semblance of amateur status as members of the army or as college students, but were able to devote themselves largely to competitive sports, supported by the armed forces or universities. That is why, as early as 1968, the federal government had asked the Ministry of Defense to set up sports promotion groups. Also to be able to compete with the state amateurs of the Eastern bloc at the games in Munich.

Financially, many 1972 Olympic champions were still true amateurs. The high jump winner Ulrike Nasse-Meyfarth recently told the SZ that she didn’t get any bonus for her victory and not even a penny of funding, instead she got angry because of a sign in her hairdresser’s window: “Here the Olympic champion gets her hair done.” The track and field association suspected paid advertising and free haircuts, which were forbidden under the amateur rule.

Heide Rosendahl-Ecker, double Olympic champion in Munich, also asserts that she has not earned any money with the sport: “I always had to keep an eye on my professional training and make sure that I had maintenance.” Of course, this also means that the amateur rule favored wealthy athletes. They could devote themselves entirely to sport without the trouble of earning a living.

Clear the stage for the pros: tennis player Steffi Graf with her gold medal from Seoul 1988.

(Photo: Sven Simon/Imago)

This dichotomy had to be resolved. At the eleventh IOC Congress in September 1981 in Baden-Baden, the amateur paragraph was practically shelved. Moreover, the liberalization of the eligibility rule should allow the best athletes to take part in the Olympic Games. “Nevertheless, the spirit of the amateur age still lingered, which confused athletes,” says sports historian Wassong. For example, the Swedish ski racer Ingemar Stenmark was excluded from the 1984 Winter Games in Sarajevo because of a professional license he had been granted in 1980. The American skiers Phil and Steve Mahre, who, unlike Stenmark, had reported their high earnings to their association, were allowed to start.

The final barriers fell at the 1988 Seoul Olympics. Now even the millions of earning tennis professionals were allowed to compete, which brought Germany a gold medal from Steffi Graf. In 1992 in Barcelona, a selection of highly paid NBA professionals from the USA, the so-called Dream Team, outclassed the rest of the basketball world. And the millionaire professional footballers mutated into Olympians. In 2008, the aspiring world footballer Lionel Messi was in action for Argentina, in 2012 Neymar, currently the most expensive footballer in history, played for Brazil at the Olympics. In 2016, professional golfers were also included in the Olympic program.

Breakthrough: The NBA basketball team, led by Earvin “Magic” Johnson (on the ball), finally paved the way for professional athletes to compete at the Olympics at the 1992 Barcelona Games.

(Photo: SVEN SIMON/picture alliance)

Nevertheless, professionalization did not make all athletes millionaires by a long shot. The development was very different in the different sports. According to a study, the gross hourly wage of top athletes in Germany in 2017 was below the statutory minimum wage. Natalie Geisenberger, six-time Olympic champion in luge, nevertheless praises the support system in German sport. Her employer is the Federal Police, which secured her basic salary and her professional training. Then there is the sports aid. “It’s not like I could wallow in wealth and have things taken care of, but I wouldn’t want to trade my sport for a little more money,” says Geisenberger.

However, in order to receive a bonus of 20,000 euros from Sporthilfe, you have to win an Olympic gold medal. In women’s ice hockey, some of the German athletes even had to pay for their overnight stays in the training camp themselves before the 2014 Olympic Games in Sochi. In some sports, the old Olympic amateur ideal is still being over-fulfilled.