Haute cuisine with a difference

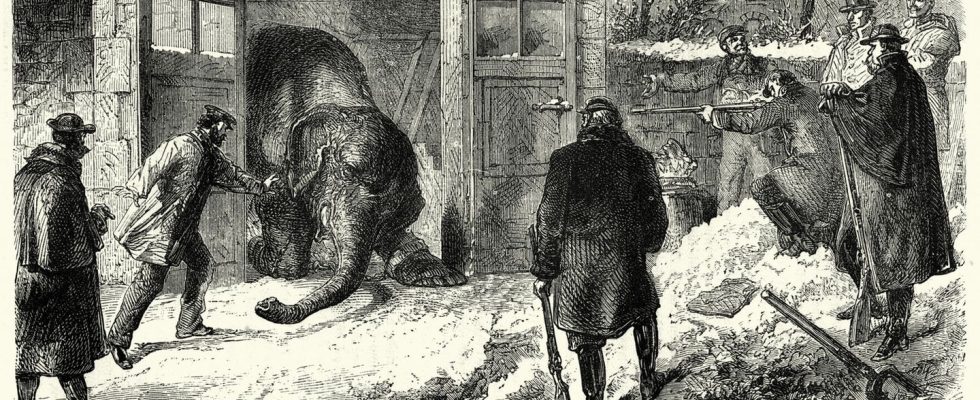

Elephant trunk and bear knuckle: The winter in which the Parisians ate their zoo animals

What does elephant meat taste like? Rich Parisians found out at Christmas 1870.

© duncan1890 / Getty Images

First the domestic animals had to believe in it, then it was the turn of the pachyderms, camels and bears. In the winter of 1870, Parisians ate everything they could get their hands on. They didn’t stop at the zoo residents either.

When it comes to cuisine, no one can beat the French. Known for their refined palate, they are masters of haute cuisine. But there was a time when it wasn’t just frog legs and snails that were at the top of the menu. In 1870 there was war and food was scarce. To ease their growling stomachs, the Parisians cooked everything they could get their hands on. Even the zoo animals.

In mid-September the people found themselves surrounded by the Prussians and the city was under siege. Although the French Ministry of Agriculture had done its best to fill the city’s larders before the siege, the Bois du Boulogne park became a collection point for cows, sheep and pigs that had been hastily carted in. But supplies dwindled quickly. The population’s hunger grew – but the siege continued. The capital was to be sealed off from the outside world for four and a half months.

Bello and Minka end up in the cooking pot

Just a month after the Germans took over the railway lines and cut the telegraph poles, there was increasing evidence of an impending food shortage. Horse meat wasn’t exactly in vogue at the time, but it still conquered the markets. There was a lot of advertising for the meat in the city. Robert Lowry Sibbet, a doctor from Pennsylvania, was stuck in the city during this time. He documented his observations in the book “The Siege of Paris by an American Eye-Witness.” In it he reports on a dinner hosted by the Central Sanitary Commission. The menu included horse broth, horse cold cuts and braised horse flank.

As a result, it wasn’t just the horses that ended up in the cooking pot. In the second month of the siege, when Parisians were now only allowed 100 grams of meat per capita per day, pets had already started to lose their fur. Rue Rochechouart was supposed to be the focal point for all those who weren’t too particular about which animal the meat came from. Dogs, cats and a special treat were traded there: rats. Everything that wasn’t human gradually disappeared from the streets and ended up on plates. Dog chop, mouse and rat fricassee and cat ragout were common on menus during the siege. In December the zoo also emptied.

There’s an elephant at Christmas

It wasn’t just the people who were hungry. Food was also scarce in the zoos. Operations could no longer be maintained. And since the animals were doomed to die anyway, the Parisians quickly decided to make a virtue out of necessity. The Voisin was one of the last restaurants in the city still open. The menu prepared there on Christmas Day 1870 went down in history.

Alexandre Étienne Choron wore his hat in the classy Voisin restaurant. Choron, known as the inventor of the sauce of the same name, a type of Béarnaise, also showed off his creative cooking skills at Christmas 1870. After it became known that the zoo animals’ last hour had come, Choron didn’t hesitate. He went on a major shopping spree and purchased large quantities of meat. Including that of the two elephants Castor and Pollux. They became part of a menu plan that still makes many people pale today.

Those who could afford it were not only served elephant broth by the famous chef at Christmas, but also roast cat flanked by rats, braised kangaroo, bear knuckle, roasted camel, wolf with deer sauce and antelope pie – with truffles, of course. In the days that followed, Choron’s menu also featured many culinary specialties such as elephant trunks with hunter’s sauce. The offer was not only permitted, it was also desired. The government’s only restriction was that it had to be clearly stated which animal had been sausageed.

Although the French at that time didn’t shy away from much to fill their bellies, the Parisians had no appetite for monkeys. Tigers and lions didn’t end up on the plates and the fine society also refrained from a hippopotamus meal. Just weeks later, on January 28, the siege of Paris ended. It wasn’t just the population that suffered. Pets had long since disappeared from the street scene. Even the poodles that the Parisians once loved so much, chronicler Sibbet noted with dismay, were missing any trace.

Sources:Atlas Obscura, Vice