At least Fasanenstraße, that sounds like a little green, even if far and wide there is nothing left of the bird enclosure that Frederick the Great once had built here. House number 88: Central Library of the Technical University of Berlin, a massive cuboid with five floors and a reasonable brick facade. Who would suspect behind this technocratic window front people who cherish and care for the rarest of plants? Taking care of the right light, regulating the humidity and above all: always admiring the beauty of the fruit and leaves. Happens daily in the German Horticultural Library, first floor, at the very back. The fact that the plants here only exist on paper doesn’t change anything. On the contrary. You need special sensitivity for this.

Appointment with Professor Clemens Alexander Wimmer, garden historian and head of the library. Wimmer is the master of more than 55,000 volumes on every imaginable aspect of plant cultivation, from handbooks on climate research to the treatise on Queen Marie-Antoinette’s park. And above all, the Berliner with dainty gold-rimmed glasses is a passionate connoisseur of old pomological illustrations, which is the first special term in the room. Pomology, the “science of fruit types”: Fortunately, the 63-year-old patiently provides visitors with information, because it is clear at first glance that there is a very special little realm in this separate glass hermitage. File boxes and stacks of gardening books stand in the way, loose copies of the Rosen-Zeitung lie on the shelves next to the “Feingemüse Varieties Guide” from 1968. Flower lovers are called “florists” here. But the most amazing thing is that the world of Clemens Alexander Wimmer is by no means archaic, but highly topical. On Instagram and Snapchat, as patterns for outrageously expensive designer wallpaper or in illustrated books: botanical illustrations from past centuries, these graceful, unbelievably detailed apples, pears or downy house quinces have recently been viewed by many as fresh rather than dusty.

In a striped look: a decorative pear variety, illustration from a Belgian horticultural journal from 1888.

(Photo: TU Berlin, University Library, German Horticultural Library)

So it’s about talking to the expert about this fascination, whereby Wimmer, as a historian, generously ignores transient phenomena of the present. It’s quite possible that chic books exist (e.g. “265 Vintage Botanical Illustrations” by Kale James) or that the noble British textile manufacturer Cole&Son has launched an orange decor. “But now we want to see something,” says Wimmer, and with expectant solemnity approaches a stone-gray trolley that his employee has prepared. Delivery from the “Rara” department, where the pomological treasures are stored in the windowless basement of the library at a gentle temperature and humidity. Famous works in which masters such as Johann Herman Knoop or the Italian Count Giorgio Gallesio more than 200 years ago put the fruits of the Lord’s garden on paper one after the other with perseverance, precision and an unmistakable stroke. Cold Berlin rain is falling outside the library windows. It’s always late summer for the pomologists with their pictures, a sunny September day full of heavy branches with Gravensteins or yellow plums. And none of it ever goes rotten.

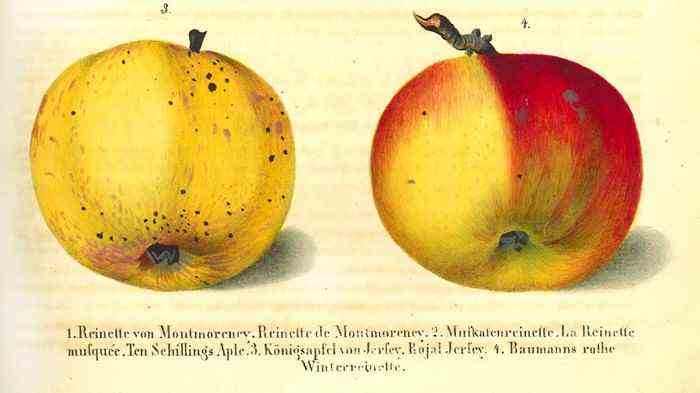

A feast for the eyes are above all the hand-colored prints by Baron Lexa von Aehrenthal, who in the 1830s depicted “Germany’s pome fruit varieties” so realistically, the skin being sometimes delicate, sometimes leathery and even with brownish scabby spots that you would want to bite into it. Much better than the waxed supermarket goods, Lexa still has varieties such as “Wintergoldreinette” and “Jersey Royal Apple”. Clemens Alexander Wimmer does not consider details such as spoiled fruit pulp or a tiny insect in the pictures to be individual ideas of the artist. “There’s nothing playful about it,” he says. It’s more about documentation that is as accurate as possible. The early pomologists saw themselves as enlighteners who cataloged knowledge and usually reproduced a fruit in different views and cuts.

In doing so, they achieve works of art that have their appeal – and their price – precisely because of the combination of attention to detail and systematic order. Wimmer keeps pausing when turning the heavy pages of paper. “These color nuances are unique,” he says, or points to the particularly harmonious composition of a pear arrangement. Is there such a thing as the Blue Mauritius of pomology, a precious trophy? “There are sheets like this, and sometimes they appear in stores,” says Wimmer. But the prices could only be paid by bidders such as the Emir of Qatar. “Today you must travel to the Persian Gulf to see these originals.” The motif of never-ending fertility, bought at auction for a great deal of money – in a weird way, it goes pretty well with the emirate with its artificial islands and irrigated green spaces.

Pomology, the study of fruit varieties, is derived from the Latin word “poma”, meaning tree fruit. Here is the title page of an academic treatise from 1793.

(Photo: TU Berlin, University Library, German Horticultural Library)

The historical images of apples, pears and mirabelle plums actually seem domestic, somehow reassuringly down-to-earth and yet pretty. This is probably why pomological reprints are so successful, whether as a luxury linen-bound volume by Taschen-Verlag (“The Book of Citrus Fruits”) or by Atelier Editions, which has just published the “Illustrated Catalog of American Fruits & Nuts”. The fascination lies in the idea of a small, orderly, useful world, just like an orchard – although or precisely because everyday life for many people is the exact opposite: complicated, uncertain, overwhelming. It’s not about suddenly a lot of people wanting to switch to apple growers. But these types of images seem to satisfy a longing for clarity and time for care. Just as the Cottagecore phenomenon has nothing to do with real country life, but takes place on Tiktok without any dirt or odours.

Anyone who only half immerses themselves in the subject of fruit growing, its history, cultivation and artistic representation will be surprised by the variety of organizations and bulletins. In addition to the German Horticultural Library, there is the Pomologists’ Association or the Orangeries Working Group in Germany; They know each other and know, for example, that Clemens Alexander Wimmer from Berlin has a special relationship with the “Bollweiler pear”, which has had its botanical abbreviation CAWimm since 2014. bears in the name. And in Munich, Iris Lauterbach cultivates her enthusiasm for the evergreen plants that people long for: oranges and lemons.

The specialist in garden art, who teaches at the Central Institute for Art History, published a reprint of the great work of the Nuremberg merchant Johann Christoph Volkamer last year: a copper engraving collection of 170 types of citrus, published from 1708, which Volkamer had sent from all parts of the world and cultivated in his Franconian garden despite the most adverse climatic conditions. Another crazy story from the amazing world of pomologists. In any case, dealing with the almost obsessed lemon merchant fascinated Iris Lauterbach on the one hand from an aesthetic point of view. Volkamer instructed the commissioned engravers to depict the fruit in its original size. In the illustrations, they float like bizarrely shaped, large-pored giant structures high above the tiny town and garden sceneries.

According to Lauterbach, she was also amazed by the enormous variety of citrus fruits known at the time, from the bitter orange to the striped orange. “That should be a fundamental concern for everyone involved in fruit growing today anyway: to preserve biodiversity,” she says. Quite apart from the taste discoveries as part of the book project. A salad made from fresh cedrat lemons, for example. “Finely cut, with salt and olive oil. It tastes so wonderful, you’ll never forget it.”