The reporters were quite astonished when they were told on August 30, 1972 that the basketball players from Puerto Rico had celebrated their unexpected 79:74 win over world champions Yugoslavia the day before, until the early hours of the morning. After all, the preliminary round of the Olympic tournament was still in full swing and the next game was already on the agenda for the evening. Of course, the reporters were even more astonished when they learned that the Puerto Ricans were already at night before had been on the road for quite a long time compared to the world champion. “Until two in the morning, several players are having fun with new friends from the group of folders (there are also girls, as is well known) in Schwabing’s relevant basketball bars,” the SZ informed its readers.

So that’s what happened among the athletes during the Munich Olympics. “It was a huge party. The mood, the weather, everything was good,” recalls Holger Geschwindner, then captain of the German basketball team: “The evening before our opening game against the Puerto Ricans, we’re up in the ‘Meadows’ with them danced on the tables.” At the time, the “Meadows” was the meeting place par excellence for the Munich basketball scene, and the German captain had also steered the party-loving sports fans from the Caribbean there. “You could walk to Schwabing from the Olympic Village,” says Geschwindner, “and everything happened in Schwabing back then.” In this respect, too, Munich lived up to its claim of hosting an Olympia of short distances.

Holger Geschwindner had explored the terrain extensively, he had already switched from MTV Gießen to USC Munich at the beginning of the 1970s – above all to experience the Olympics and absorb its flair, to inhale the attitude to life of a thriving city. It also had a lot to offer him as a student of mathematics and physics. To this day, he is impressed by the tent roof construction and its calculation, without any computer programs. “It’s still a highlight,” he says half a century later.

Even after 50 years, still impressed by the 1972 Olympics and everything that went with it: Holger Geschwindner, a basketball player at the Munich Games.

(Photo: Claus Schunk)

Munich had developed a strong attraction through the Olympic Games. The city opened up to the world and to modernity; in the wake of the sexual revolution and enlightenment, a certain permissiveness spread. A decade after the introduction of the contraceptive pill and a decade before the onset of the immune deficiency disease AIDS, young people were able to try out what was possible without any worries. And not only from a sexual point of view, a lot was possible. For example, taking part in a demonstration by a communist group in a Porsche, as Geschwindner once did at the time. He got into it by accident, he assures, and a few demonstrators just sat in the car and let them take them along Leopoldstrasse at walking pace. Live and let live, it worked back then.

Originally, Geschwindner, who comes from a family of architects, wanted to invest the money he had saved and his parents had given him in a Jaguar E-Type, he says: “But I couldn’t use the gas pedal with my shoe size 50. Everything was right with the Porsche. ” Young, high-spirited and hungry for life – that was the Munich ’72 generation.

That summer, the photos for the first edition of the German playboy made with a Munich student and comparatively chaste. The women sunning themselves in the grass next door wore lighter clothing. “Barefoot right up to the earrings,” says Geschwindner. At that time, the image of Munich and the naked people in the English Garden was shaped, which was described in American and Asian travel guides for a very long time and animated hordes of tourists to stop by.

Munich freedom of movement: when a fashion store promises to dress the first five naked customers free of charge shortly before the Olympic Games, more than 100 students storm the store.

(Photo: Heinz Gebhardt/imago images)

And then in August the athletes also came to the city, “ten thousand well-formed bodies”, as Geschwindner recalls: “You can imagine that the hut was on fire. The city was buzzing.” And the athletes admired each other. “They’re all world class, and you don’t even know many of them,” says Geschwindner: “But this knowledge that they’re all at world class level – that’s an insane feeling, you can’t get it on the roll.”

He remembers the moment when the Cuban heavyweight boxer Teofilo Stevenson came into the sauna in the Olympic Village, 1.90 meters tall, muscular and modeled like a Greek statue: “You could have put him on a pedestal right away.” Or the Soviet Russian weightlifter Vasily Alexeyev, rather wide than tall. “He looked as if he couldn’t knock over a glass of water,” says Geschwindner; but when he and his team came into the training hall after the three hundredweight super heavyweight, “six of us rolled the dumbbell off the stage that he had previously lifted up”.

The young people of the world met and amused themselves in the Olympic Village. “Everything was extremely relaxed,” enthuses Geschwindner. At that time, this extreme looseness also included the generous interpretation of the specifications of the organizing committee. “There were rules that you had to be in the Olympic Village by ten o’clock in the evening,” Geschwindner remembers, “but I don’t know who followed them.” He suspects the athletes from the Eastern bloc were generally considered disciplined and controlled in every respect. “For everyone else it was clear: It’s going to be a huge party.”

With the assassination, the mood changes

And then came September 5 and the attack by Palestinian terrorists on the Israeli team. “If someone intervenes in the middle of the party, it’s a huge shock,” says Geschwindner: “No one knew how to react.” The basketball players stood in the Rudi-Sedlmayer-Halle in the afternoon and waited for a decision as to whether they should play against Australia as planned or not. It went into the locker room, back out onto the field. More than twelve hours into the drama, it was decided that the teams had to compete. But Holger Geschwindner and his teammates – and not just them – were out of breath, their spirits gone.

The joie de vivre of the people of Munich was only dampened for a short time, the lightness and cheerfulness of the games had long since spread to the city and were to shape it for a few years to come. Music producer Giorgio Moroder was inspired to create his Munich Sound after the Olympics Rolling Stones came to the Musicland Studios for their next recordings, Queen singer Freddie Mercury was also a constant visitor. The film and television director Helmut Dietl immortalized the light and frivolous attitude to life of that post-Olympic period in series such as “Der quite Normal Madness”, “Monaco Franze” and “Kir Royal”.

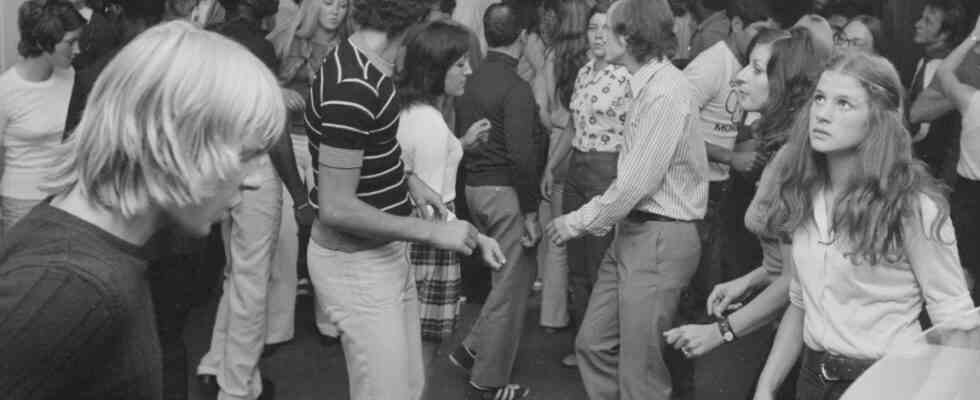

There is dancing in the club in the Olympic Village – after that the partying continued in the apartments or in Schwabing.

(Photo: SZ Photo)

In the meantime, of course, things are more tranquil and leisurely in Munich, sometimes even more prudish. The recently resurrected debate, for example, whether female breasts should be covered when swimming in Munich’s pools, was settled in the early 1970s. Hardly anyone lies down naked in the English Garden, which is probably not necessarily due to modesty, but more to social media. The rapid dissemination of images probably keeps many from showing themselves too freely in public.

Several thousand condoms are distributed today

After 1972, the venerable Olympians reacted to social developments by abolishing the strict separation between men’s and women’s villages that still existed in Munich. The organizers are now complying with the striving for non-sporting pleasure that cannot be stopped at the games anyway by providing the athletes with several thousand condoms. The exact number will be announced before the start of each event, as well as when they will be used up.

But the sports scene also seems to have peaked when it comes to parties. In any case, at the European Championships recently held to mark the 50th anniversary of the 1972 Games, the athletes were very cautious. “We’re happy if we can keep to ourselves,” said Jonas Wiesen, the helmsman of the Germany eight. Due to the selection of the German Rowing Association, several corona waves have already swept over this year, he says: “We can’t afford that.” Athletes today are also more clocked than they were back then.

Rowers, triathletes, cyclists, for example, left immediately after their competitions in Munich for the next training camp, the next competition, the next sponsorship commitment. There’s almost no time to celebrate, especially between competitions like Puerto Ricans did in 1972. Nowadays it’s about performance records, squad affiliations, sports aid. The amateurs from 1972 approached things much more light-heartedly, Holger Geschwindner thinks: “We didn’t have it any better, but we knew it could only get better. Today everyone thinks it can only get worse.”