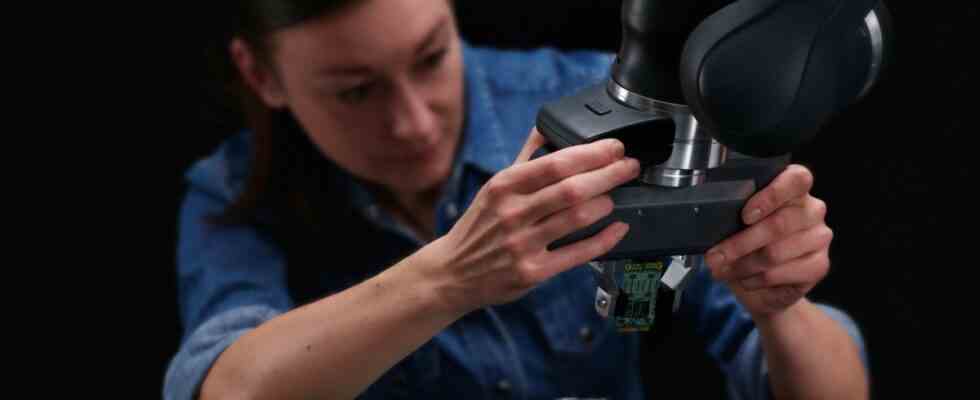

Franka likes to be taken by the hand. Or rather: If you want to start something with Franka, got to take her by the hand. Have to show her exactly what to do. Without much resistance, her arm can be moved here and there, grasping something or working with a tool. It’s not difficult at all to teach her, and she has neither eyes nor ears. Franka Emika 3, her full name, is a robot. The learned movements are then saved – the program is complete.

When you think of robots, you might think of Arnold Schwarzenegger in his role as “Terminator”. Or giant machines that heave extremely heavy engines into car bodies, paint sheet metal and set spot welds – and all this 24/7. In car factories, they have long been the norm. But a new category has long since existed between the rather stupid large robots, which always only dullly carry out their job, and the man-machine from the future. Robotic arms, about twice the size of a human arm, are just as resilient as their larger counterparts. But they are much more flexible and can be trained by people who have little or no knowledge of the intricacies of robot programming.

This category is called cobots. The Co in the name means that these machines should not work instead of people, but with them. The industry hopes that this will finally open the door to many small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) – it would be a multi-billion dollar market. But there is still a lot to do. It is true that SMEs have many activities in their production facilities that could easily be carried out by a robot. But they often don’t dare to approach the topic. It was the same for Frank Reinauer. The experienced production professional heads the production and innovation departments at the Stuttgart medical technology manufacturer Leibinger. He used big welding robots before, but they were extremely expensive. And programming them requires experts from the manufacturer. Change something quickly, put another product in between – no return.

But then Reinauer walked past the booth of the Constance start-up Fruitcore Robotics at a trade fair. And was surprised: “I was able to program a complex process myself at the stand,” he says. That was also the goal of the Greens Jens Riegger and Patrick Heimburger. A robot, says Riegger, must be as easy to use as an iPhone, but still suitable for jobs in industry.

Medium-sized companies are the “holy grail” for designers

In any case, Reinauer was convinced. As part of a master’s thesis, a student integrated the start-up’s robotic arm, called “Horst”, into the production process at Leibinger. The aim was to subject joints for prostheses to a stress test. “After six months we had a perfect result,” enthuses Reinauer. And at a fraction of the money he would have spent on a standard industrial robot. It would have cost him almost 200,000 euros, “Horst”, on the other hand, burdened the budget with less than 30,000 euros, the production manager is happy to say.

The robots from other manufacturers are also around the same level. They are all competing for the small and medium-sized enterprise market, the “holy grail” as Andrea Alboni calls it. The Italian manages the business of the Danish manufacturer Universal Robots in Western Europe. So far, SMEs have shied away from using robots, he says. They don’t have robot programming skills, unlike the auto or electronics manufacturers. And robots commonly used in industry are expensive. Which is still worthwhile, because it’s about manufacturing large quantities, vulgo: mass production.

It is different in a craft business or other smaller companies. A carpenter, for example, builds this piece of furniture one week, windows the next and something else the week after that. A robot system that can only be reprogrammed by experts and with great effort is of no help to him. This is exactly where manufacturers such as Universal Robots, Franka Emika or Fruitcore Robotics come in. They are all supplied with software that also enables robot laypeople to quickly and easily teach their automatic helper what to do.

“Many could benefit from robots,” says Andrea Alboni of Universal Robots, “no company is too small.” At first glance, that doesn’t sound surprising for someone who ultimately wants to sell their products. But he has very good arguments: “Often it’s about moving parts from A to B.” That’s dull and boring. “One always thinks of the film with Charlie Chaplin.” People should be different than in “Modern Times” With work on the robot, not how a robot. Some things are also physically challenging. The drilling machine manufacturer Hilti, for example, developed a system together with Universal Robots that drills holes in ceilings.

The robot takes over the monotonous work, the employee the creative one

Or welding. Not only is the work exhausting and bad for your health due to the pollution of the air with pollutants. There is also a shortage of thousands of welding technicians in Germany. The job is on the list of shortage occupations – just like that of many other skilled workers. The use of robots can not only help by having the devices perform repetitive and boring tasks and thus replace personnel that are already difficult to get. At Leibinger, the medical technology manufacturer, says production manager Reinauer, job destruction was never an issue either. “It was more like it was welcomed because it shows that we are up to date.” And the human employees can focus more on what is fun about their job, the things that require human intuition and manual dexterity.

The robots are getting better and better at the latter. Alwin Mahler, the boss of the Munich robot start-up Franka Emika, therefore prefers to have his company’s devices called tactile robots, not just boring cobots. A sophisticated, multi-stage system of sensors and motor control enables the Munich-based robotic arm to carry out even difficult tasks with the necessary sensitivity. The company is a spin-off of the German Aerospace Center (DLR), one of the founders is Sami Haddadin, professor at the Technical University of Munich and recognized as one of the best robotics scientists in the world. The fact that he returned to Germany from the States a few years ago was celebrated as a minor sensation.

The step was not illogical, after all, Germany has long been at the forefront when it comes to production technology. Alwin Mahler, a manager with experience in the technology industry, says that this also applies to robotics, which ultimately takes production methods to a new level. A level that may also allow some products to be made in-country again, says Andrea Alboni – at lower cost and without the logistical problems that have recently challenged the concept of globalization.

In the case of Franka Emika’s robots, this already works to a large extent. Except for the electronic components, they are manufactured by a medium-sized company in the Allgäu. And mostly by the robots. Mahler: “They practically build themselves.”