It cannot be a coincidence that at the end of this research the Fantastic Four sneaks into the head. “It could all be so simple, but it is not”, they sing in the song “Simple to be”. Because the question at stake is simple. Actually. Should e-books be checked out in public libraries at the same time as printed books? Unfortunately, the answer is that this feeling arises after phone calls and emails with publishers, library associations and ministries, anything but that. A tough argument rages on the question. But from the beginning.

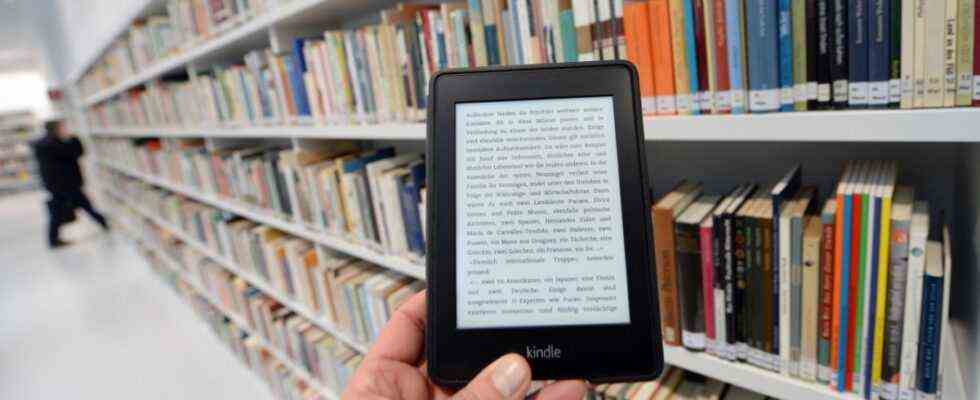

In Germany, it is common for bestseller novels or hip biographies to appear quickly on the bookshelf of the city library around the corner after their publication. The institutions acquire the new publications and are then allowed to lend them to their members. To compensate, the federal and state governments pay a library royalty to publishers and authors. So far, so easy. The system does not work for e-book lending, libraries have no right to be able to include every e-book on the market in their assortment. At the moment they have to negotiate separately with each publisher about the licensing of digital books through an intermediary and often accept restrictions.

The result: Many of the current bestsellers, which are not popular with regular customers of the “Onleihe”, appear in the online library’s range of products at a late stage or never at all. This is because many publishers do not make their bestseller e-books available for rental until months or even a year after they have been published. Delaying is known in the industry as “windowing”. The companies hope to sell more books. Bad for the libraries.

Last week, only 30 percent of the fiction titles were available in Hessen

Who at the end of last week about the online loan portal of the Munich City Library opened and the title of the current mirrors-Best seller list in the fiction category in the search field only found six out of 20 books. Stephen King’s “Billy Summers” or Juli Zeh’s “About People”: Unfortunately not available. A network of libraries leads in Hessen detailed statistics about the “embargo” for parts of the bestseller list. According to this, only 30 percent of the fiction titles and 20 percent of the non-fiction books were available in the online library last week. The libraries have been waiting for the novel “Der Buchspazierer” by Carsten Henn for more than 320 days.

“I see the risk that libraries will be dried out as a result,” says Andreas Degkwitz, chairman of the German Library Association (dbv). “You are not in a position to make current and contemporary offers. That could make you uninteresting in the long term.” For years his association has been pushing for publishers to be legally obliged to fully e-lending. It is time to promote digitization in the field of public education, he demands.

“You understand, it’s about our existence,” they rap Fantastic Four further – a sentence that could also come from the interest group of the libraries. Under the motto “A book is a book”, the dbv insists on legal equality between printed and digital books and formulated it in January an open letter to the members of the Bundestag: The legal basis must be changed, it said, otherwise the “communal cultural and educational infrastructure of public libraries will be undermined”.

The conflict between libraries and publishers is escalating

So far, publishers have successfully fended off pressure from libraries. A move by the Federal Council to include digital lending in the amendment to the Copyright Act was not approved by the Bundestag. Also thanks to the publishers’ vigorous lobbying. In their coalition agreement, the Union and the SPD agreed to give library users “even better access to the repertoire of e-books”. When asked what the government had actually achieved to achieve this goal, the lead Ministry of Justice replied evasively. “The main focus” in the area was on the copyright reform passed in the summer – “a very extensive and controversial” project. In other words: The topic of e-lending really had no place on the agenda.

“A compulsory license,” says Nadja Kneissler, “would not be economically feasible for publishers and authors. Because a borrowed e-book only brings in a fraction of what is earned from an e-book sale.” Kneissler is a manager at the special-interest publisher Delius Klasing and chairs the publishers’ committee of the German Book Trade Association. If the state were to oblige companies to license e-books, it would be “a kind of expropriation of intellectual property,” she says. Nobody complains that the new “James Bond” is initially shown in the cinema and will only be available for rental months later as a DVD.

“The film industry is windowing all the time,” says Kneissler. “In the book market, this only affects very few titles.” Thousands of e-books would be offered to libraries immediately. At the same time, online lending accounts for 40 percent of total e-book consumption in libraries, but only accounts for five percent of sales. “There are now more and more people who pay the membership fee for the library and then read countless e-books for free,” says Kneissler. Digital books are not to be equated with the printed versions: They do not wear out, never have to be replaced and can be conveniently borrowed from the couch. “It’s great for people, but publishers and authors also have to make a living.”

“This world is in the bad”, they say Fantastic Four, “And above all, she finally needs a decision” – but that is a long time coming in the dispute over e-book lending in libraries. The dbv chairman Degkwitz doubts the claim that e-lending would massively damage the book sales of publishers. “Our customers are among the most active buyers of books,” he says. “They wouldn’t suddenly stop buying literature.” He believes that the book industry is instead damaging itself by depriving itself of the advertising effect among the many library users. Degkwitz hopes that a new government will take up the issue again after the election.

Expropriation, coercion, open letters. The conflict between libraries and publishers is fierce, and both depend on good cooperation. And if you talk to publisher Kneissler and library representative Degkwitz in quick succession, the rifts suddenly don’t seem that deep anymore. E-lending is a model that will become even more important in the future. “We’re not kidding ourselves,” says Kneissler. However, a “fair” remuneration model must be created that does not exhaust publishers and authors financially.

The dbv man sees it similarly: Yes, you have to ensure “reasonable” payment – only the libraries have very limited financial leeway. That is why flexibility is needed on both sides. “We and the publishers have a common interest in maintaining the printed and digital book culture in Germany,” says Degkwitz. A solution will definitely be found at some point. What were they singing again Fantastic Four? “But what you need is trust and imagination”