His heart is heavy, his idol trapped, possibly already dead. “And is he still alive or have you murdered someone that I don’t know,” complained Albrecht Dürer in his diary in 1521. At the Reichstag in Worms, Martin Luther refused to renounce his faith in front of the emperor, but the imperial ban was imposed on him. As word soon got around, Luther, this “successor of Christ and of the true Christian faith”, was not dead at all, but was only apparently attacked on the return journey from Worms. His elector had had him taken to the Wartburg, where he was safe from the pursuit of the imperial family.

Little does Dürer suspect that he himself was in the midst of an upheaval at that moment. The painter is in Antwerp in May 1521. The year before, he had traveled to the Netherlands, hoping that Charles V, who declared Luther outlawed, would extend his annuity. In addition to this main project, the diary records many encounters and above all records the expenses that arise for him, his wife and the maid he is taking with him. The only thing that stands out in this account book is the eloquent Lutheran complaint, presented in an incredibly angry tone, which increases to hatred of the church authorities, especially the Pope.

The innocent blood that the “babst, pfaffen and the munich shed”

As an emotional outburst, the so-called Luther Lament is one of the great texts of the Renaissance. For Luther biographers, including this author, it has always served as evidence not only of how quickly the new doctrine spread, but also of the expectation of salvation associated with the reformer. “Oh God, is Luther dead, who will carry us forward with the holy gospel so clearly?” Sighs the diary writer. The complaint ends with an extra high-voiced quote from the Revelation of John: “They are slain, under the altar of God ligent”, and these dead would because of the innocent blood that “the babst, Pfaffen and the munich [Mönche] shed, “cry out for vengeance.

The text is a foreign body in the otherwise simple notes. This raging torrent of words is followed seamlessly by the most sober prose of an economical medium-sized company: “But I have 1 gulden to eat [Essen] changed. But I have 8 stüber to the doctor [Groschen] give. Item 2 eaten with the ruderigo. “How does that go with blood and vengeance?

The Dutch art historian Jeroen Stumpel has now provided evidence for the first time that the lawsuit cannot have come from Dürer, and at the same time he identifies a plausible author. Stumpel’s investigation has appeared in a remote place and yet visible to all: In the catalog of the exhibition “Dürer was here”, which was shown in Aachen until October and can now be seen in a different form in the National Gallery in London.

Art historians have always had trouble explaining Dürer’s outburst. It is known that the Nuremberg painter revered Luther as a “Christian man” who, as he wrote in a letter, “helped him out of great fears” in good time. He would have loved to “grease it up”, that is, to portray it, which he did not succeed in; he never met him. According to a list he made himself, Dürer owned sixteen of Luther’s pamphlets.

“O Erasme Roderadame”. Albrecht Dürer drew Erasmus of Rotterdam in 1526. But did he also know how to address him correctly in the vocative?

But that does not explain the direct address to Erasmus von Rotterdam, in which the complaint suddenly falls, “O Erasme Roderadame”. The author appeals to the world-famous scholar to stand against the “unjust tyranny of worldly violence” now that Luther may have already been killed, otherwise he would be “an old man” https://www.sueddeutsche.de/ culture /. “Listen, you knight of Christ”, demands the author, “Ride out next to the Lord Christ, protect the truth, attain the martial cron!”

Apparently the text comes from an Antwerp prior named Jacobus Probst

Erasmus didn’t want to be a knight at all, he didn’t care about the martyr’s crown, after all, he was lifelong dependent on donations from high and highest rulers who financed him the fruits of his cleverness. He rejected the Reformation. The new doctrine was dangerous, but scholars and ignoramuses alike joined it in the Netherlands. Antwerp, where Dürer stayed for most of his Dutch year, was a center of the Protestant rebellion. Erasmus wrote to Luther on May 30, 1519 and reported on the uproar caused by his writings and that “the prior in the local Augustinian monastery, a truly Christian man who adores you above all else”, describes himself as a student of Luther. This prior is Jacobus Probst, and he actually studied in Wittenberg with the professor for biblical interpretation. In May 1521, when the news of the sudden disappearance of the reformer arrived in Antwerp, the prior happened to be in Wittenberg again, where he was earning a baccalaureate.

For Strumpel, this provost is the real author of Luther’s lawsuit. In his – if it should be correct – pioneering attribution, the historian argues strictly philological: As a craftsman without a higher education, Dürer hardly had enough Latin to address Erasmus with the Latinized form of the original name Rotterdam and to form the correct vocative. Dürer could only understand Luther’s German texts. At the beginning of 1520 he asked Georg Spalatin, the Chancellor of Elector Friedrich, to send him “where doctor Martinus makes ettwas news, the tewczsch”, in other words in German.

Probst, on the other hand, was like Erasmus an academic, was like Erasmus and Luther Augustiner and he knew Luther personally, who in his letters did not refer to him in his letters as a “fat Flemmichen”, a fat Flemish. Unlike Erasmus, Probst fell victim to the Counter-Reformation, which struck in the Netherlands immediately after Luther’s appearance at the Worms Reichstag. He fell victim to the Inquisition, had to renounce his apostasy, immediately regretted his apostasy, preached like a Reformation again, then fled to Wittenberg, where he did the same for Luther, left the order and married. At the instigation of his master, he became superintendent in Bremen.

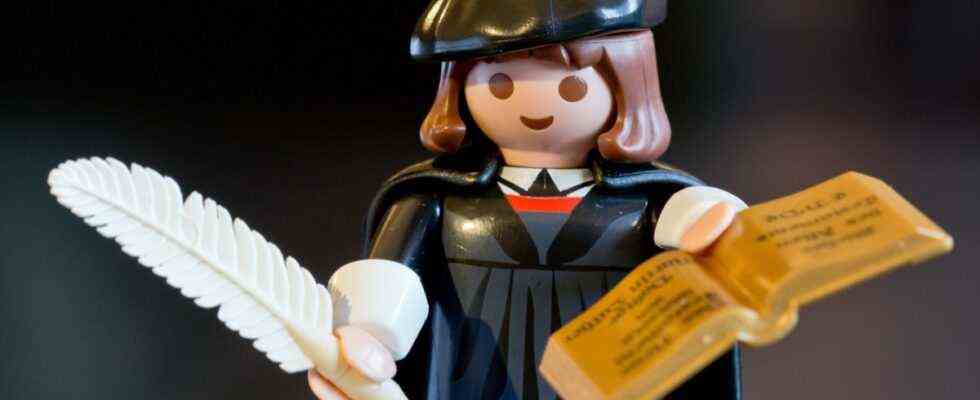

Martin Luther, painted by Lucas Cranach. Unfortunately, there is no Luther portrait of Dürer.

(Photo: Hulton Archive / Getty Images)

The unjust tyranny of secular violence, however, was far from being removed. Probst got away with his life, but his two brothers from Antwerp, Jan van Esch and Hendrik Vos, were burned at the stake in 1523 at the behest of the emperor, to whom Dürer owed his beautiful pension.

Martin Luther regretted that he could not become a martyr

The original of the diary of the trip to the Netherlands has not survived, there are only copies that were made a hundred years later. The sheets with the Luther complaint that Dürer may have received in the Augustinian monastery, where he regularly dined and met the brothers, was apparently captured by Dürer himself as a document and thus part of the text corpus. Stumpel interprets the lawsuit as an interpolation of a report that the provost, who was matriculated in Wittenberg during those turbulent weeks, sent to his confreres in the Antwerp monastery when he learned of Luther’s arrest.

Martin Luther, who was never unfamiliar with the Depression, for his part regretted that “although I would have preferred to have suffered death from the tyrants …”, he could not become a martyr, but had escaped the worldly authorities with intact skin. Unlike his admirer Jacobus Probst, he never lost faith in this authority. When the peasants appealed to his theses, he called on secular power for help. “It is better that all the peasants are slain than the princes and authorities.” Consequently, the 19th century made him a national saint. The Hohenzollern put a Prussian hood on their castle church, and Wilhelm II demonstratively drank from the Luther cup in Wittenberg. Only the pastor’s son Friedrich Nietzsche resisted when he groaned in “Ecce Homo” in 1889: “Luther, this fate of monk, has restored the church and, what is a thousand times worse, Christianity, at the moment, where it was subject.“