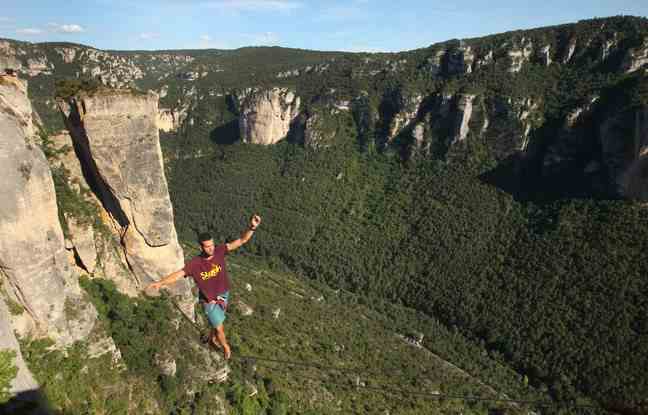

The Eiffel Tower, the Palais des Papes, Mont Saint-Michel, or even Lake Annecy on July 19… All the emblematic sites of France, and even far beyond, are crossed by Nathan Paulin. The 28-year-old highliner from Haut-Savoyard tells 20 minutes how he built an unexpected professional life by chaining exploits at (very) high altitude on his webbing.

Anyone who remembers having “really freaked out” once, attacking the towers of the City of Moscow in 2019, more than 300 m high, retraces his dizzying journey, symbolized by his recent world record of the longest crossing on a slackline. On May 24, in a crazy project that mobilized 35 people, this modern-day tightrope walker traveled the 2,200 m between a crane (114 m from the ground) and Mont Saint-Michel.

What memories do you have of your first steps on a slackline?

A friend of my brother showed me this in 2011. As I was bored during the summer at Reposoir (Haute-Savoie), I got a strap from my parents’ garage and hung it between two trees in the garden. Like everyone else, I was shaking over short distances. I started to do almost nothing more than that in my free time. I can be very distracted and slacklining totally captivated me. I was quickly taken by the virus and I started trying longer and longer distances, to increase the difficulty and find this state of intense concentration. But I didn’t realize at all that it was going to change my life.

Looking back, do you think you had a predisposition for this practice?

I was quite sporty, I ran a lot in the mountains. But I think anyone who can stand on their own two legs can quickly become good at slacklining. I improved in a few weeks, because I especially felt something addictive: I needed to spend a lot of time on the strap. I really liked the state I was in when I practiced, so I practiced it every day and in all weathers, even at night in the snow. I even wondered what else I could do before, it had taken so much space in my life. And then via the Internet, I came into contact with the Flying Frenchies, who were the pioneers in France of this very community discipline. I went in just three months from a solo practice at ground level to my first time in the void with them at the Trois Pucelles cliff, above Grenoble. I suddenly had more than a hundred meters under me…

Switching to the highline, was that a revelation for you from the outset?

No, this first crossing was a big slap. I said to myself that it was not at all made for me (smile). It terrified me and I wasn’t at all interested in scaring myself. I didn’t have the right technique for the sit start and I fell straight away. It was much more difficult than at ground level, it had nothing to do with it.

Why and how did you then stick to the highline despite everything?

I resumed at ground level, then I quietly started again in the void. To combat this fear of heights, I started listening to music, especially pop-rock, which helped me a lot. When I’m on a line, I’m more sensitive to the music. It put me in a bubble, in confidence and I felt less empty that way. Each time, I was like, “What the hell am I doing here? but I came back almost every weekend. It’s a bit like learning to walk when you’re a baby. We fall and hurt ourselves. It’s quite violent, it requires a lot of strength and determination. But once you know how to highline, it becomes soft and you can practice for a long time.

How did you come to consider making your passion, then extremely confidential in France, a profession?

I was finishing a mechanical engineering DUT in 2014 and I was invited to a highline festival for two weeks in Iran. Even if it means going there, I decided to devote a sabbatical year to slack. At the end of this sabbatical year, I was offered a job in 2015 in a bar turning factory in Haute-Savoie. But a few days before starting this first job, a guy offered me 300 euros per month to participate in some slackline events. It was my biggest leap into the void and I am very happy to have made the decision to refuse this job in bar turning, with the support of my mother. In June 2015, I beat the world record in the vacuum for the first time in Reunion with 403 m in length, and it was on. Then in December 2017, connect the Trocadero from the Eiffel Tower (670 m in length) really revealed to me in the media, even if the project fell at the same time as the death of Johnny Hallyday (smile).

In your opinion, why are you the only professional highliner in France today?

Being a bit multi-tasked helped me and set me apart from others. I have always been handy and resourceful. When you have to put your life on a line, it takes a lot of confidence in the installation. Before each crossing, it is also necessary to obtain authorization from the authorities. I got into the habit of arriving with a super clean technical file and a reassuring speech to convince them. I spend a good half of my professional time setting up facilities that can be complex, such as the 2,200m Mont Saint-Michel, where it took me six months full-time. I think I handle pressure better than others, like when you have to jump from the Eiffel Tower live for the Telethon, with the crowd below.

Just how much can your sensations fluctuate once you launch yourself on the strap?

My feelings are linked to the projects. I’m not going to feel the same when I do my record crossing on Mont Saint-Michel, where I test my limits of concentration, with my arms in the air for 2 hours, or when I run 30 m in a theater to a show. In this context, I aim above all for the perfection of movement and the transmission of something beautiful. Today, I am much more serene on my crossings, even if my first steps are always a bit difficult. Then I find myself in a feeling of freedom, of well-being, of control of what I know how to do. When I walk on very long lines, it’s a bit like a trance, all the movements are automatic. I can also play with the line, sit or lie on it to get different sensations.

After ten years of highlining, can the adrenaline of crossing the void sometimes give way to almost routine, even in such an extreme discipline?

Yes, there can be a form of routine. Some projects can even bring more adrenaline to the spectators than to me. And then I have to control any adrenaline rushes. Because as much as it can be positive for a very short time in order to be ultra attentive to everything on the line, it is untenable to be under adrenaline for 2 hours. Today, thanks to the contribution of the slackline, I can face life situations in general with much more serenity.

Isn’t it sometimes difficult to come down from your strap, where you feel “free”, to rediscover real life?

Yes, it can still happen to me when I live a very intense experience. There is always a form of blues afterwards. But I’m doing so many unexpected projects that I’m well aware of all that slacklining has given me in my daily life. Before her, I had gone through times when I was really not well during my studies. I was stressed and prone to bouts of depression. There, I’m doing something that I really like and I’m sure I’ll still have fun in two years.

From your record at Mont Saint-Michel, for example, you announced that you dreamed of a crossing between the Eiffel Tower and the Montparnasse Tower, i.e. 2.7 km in length…

It’s true, but there’s no exact date yet, and it won’t be before 2023 or 2024. Anyway, thanks to the highline, I’ve already been to China 12 times, and I never would have imagined finding myself one day on the bill of a show played at the national theater of Chaillot (Paris 16th).

What does this “Extreme Body” project by Rachid Ouramdane, which will be touring in the coming months in Lyon, Brussels, London, Madrid, etc., bring you?

It is an aerial ballet that brings together acrobats and athletes while relying on testimonials. It allows me to make my practice understood by the spectators, and thus to break the image of the “crazy at the top” that they sometimes have of me. Sharing a performance with other artists is super interesting.

What does the Haut-Savoyard represent for you, this next new project of July 19, with 800 m of slackline, 50 m above Lake Annecy?

It will be strong because it is the crossing that I made by bike to spin from my student apartment to the park where I installed my slackline at ground level at the time. The Bonlieu theater is organizing this evening, as part of the Annecy Paysages festival, and it’s going to be poetic.

While the general public sees the highline as a crazy sport, is your serenity still total?

No, and that’s what can tire me the most in my practice. With each new project, I know that I am putting my life on the line. There are different security issues, so it constantly pushes me to think and it is a bit exhausting on a daily basis to always have to master everything so that things are going well. In most other trades, if things go horribly wrong, people can lose money or get fired. Me, if there is once a failure, I am dead, there is not really an alternative…