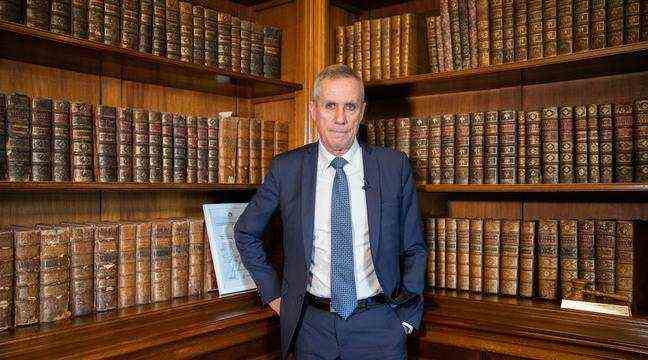

Rarely has the face of a prosecutor been so familiar to the French. Like the dark outfits of the Raid police and GIGN helmets, the serious face of Francois Molins imposed itself after each jihadist attack perpetrated in France when it occupied the post of public prosecutor of Paris, between 2011 and 2018.

Mobilized on the evening of the attacks of November 13, 2015, this senior magistrate, who has since become attorney general near the Court of Cassation, has not forgotten anything of that night. On the occasion of the opening of the trial of the attacks on Wednesday, François Molins returns to 20 minutes on the personal and professional consequences of these terrorist attacks.

Six years after the attacks, what do you remember from this evening of November 13, 2015?

It’s complicated to talk about this, but what I can say is that everything that happened that night is present in my head with the same precision and intensity as if it had happened. produced three months ago. I remember everything I did that night and the weather had absolutely no effect on the accuracy of the memory.

Did this event change you personally?

I wouldn’t say it hardened me, but maybe it strengthened my capacity for outrage at certain things. I think it certainly helped make me more open and sensitive to the suffering of others.

Have these attacks changed the exercise of the profession of prosecutor?

They haven’t fundamentally changed things. I always say that it is normal to have emotions in the performance of our duties, but that we must manage them so that they do not disrupt professional practices.

What is certain, however, is that the management of the attack and its consequences could have referred to certain things – I do not know whether to speak of deficiencies – which could have worked better and which could be improved. This then resulted in a dynamic aimed at modifying our systems, adapting penal policy and strengthening our partnerships with intelligence services, for example.

After the discovery of the crime scenes, you were assigned to oversee the start of the investigation. What was the most complicated or the most difficult to deal with at the time?

The biggest difficulty is the multiplicity of everything you have to do very quickly and without making a mistake. First, you have to qualify the facts – are they terrorists or not? We must choose an investigation service, designate the one who will coordinate the investigations. Then it is necessary

launch the crisis unit system, coordinate the action of the prosecution to enable it to organize itself and be present at all crime scenes. We must launch the victim assistance systems, since we have the obligation to report very quickly to the Guarantee Fund for Victims of Terrorism (FGTI) the single list of victims. We are also responsible for launching the forensic medicine systems: who will be autopsied and where?

At the time, to accomplish all of these missions, the crisis unit brought together a dozen magistrates, and we were able to mobilize 37 in the space of two weeks which took turns night and day, seven days a week. And finally, communication and international cooperation in criminal matters had to be launched, which in this dossier was of major importance. The real difficulty is managing to carry out all these responsibilities and meet all these challenges head-on.

How do you keep from collapsing under the pressure?

I do not know ! We tried to do it, anyway, and then it’s a team effort. I had a cabinet with magistrates around me, as well as the anti-terrorism section. After all, it’s all a question of organization. What is certain is that having been in this position during the Mohamed Merah attacks in 2012 and those of Charlie Hebdo and the Hypercacher in January 2015 has strengthened our experience. It allows you to think about what you have done right, what wrong, and what needs to be corrected to pull things up.

What can we expect from the debates that will open on September 8 before the special court of assizes in Paris?

I think a lot can be expected from this trial. The file does not appear at all like the file of Charlie hebdo and the Hypercacher, where the truth could ultimately only be established on one side of the file. We were able to make progress on what allowed Amedy Coulibaly to prepare his attack but lots of questions remained before the trial – and will always remain – concerning the preparation of the Kouachi brothers. In the case of November 13, this is not the case at all. The investigation was colossal, the investigation has more than 400 volumes, and we realize that the investigations made it possible to cover the case.

The other difference is that the network of the attacks of November 13 includes about thirty people. Fourteen defendants will appear before the special assize court in Paris and there are some among them who are accused of extremely serious matters relating to preparation and participation in the attack. We can therefore expect much more than the January 2015 trial in terms of the manifestation of the truth. The audience must make it possible to demonstrate everything that happened, the role of each and their connections.

In your opinion, can this trial be of interest to society as a whole?

Yes really. An attack like this creates a lot of fear and anxiety in society. The state has a specific function of protecting citizens. The role of justice is to name things, to arrive at the manifestation of the truth and to condemn the guilty. From the moment she fulfills this office, I think that it participates, in a certain way, in the management of the fears of the society, and that helps in the work of reconstruction and resilience of the victims.

You will be called as a witness at this trial. For what reasons, according to you?

It’s quite innovative – it has never happened to me in my 40-year career. It is a rather special role of witness. If I am quoted, I think it is to give my vision of things, to recall the main axes of the investigation when it was launched and to come back to the climate in which we were before, during and after the attack. I have not yet prepared my testimony [l’entretien a été réalisé le 21 juillet], but that does not cause any concern on my part.

The Chancellery has never had to take up such a logistical challenge to organize a trial, with 1,700 civil parties, nine months of hearings, high security and health risks. In this context, will justice be able to render itself correctly?

It must take place calmly. The trial could have taken place elsewhere [qu’à la cour d’appel de Paris], but it is better that he can stand in a place of righteousness. And there is no place more symbolic for justice than the Île de la Cité! The institution has given itself the means to ensure that the facts are examined and judged calmly and efficiently. There is no reason for this to go wrong, we just have to hope that the health crisis does not come to shake up all that.

What is your analysis of the current terrorist threat in France?

The risk has changed a lot. We are no longer in the situation we experienced before the 2015 attacks, with a very high risk of attacks planned and organized from outside. Today, Daesh no longer has the capacity to carry out this kind of operation. The latest analyzes speak of “atmospheric terrorism”. We are confronted with radicalized individuals, who can sometimes suffer from psychological or psychiatric disorders and who, in a rather tense climate, against a background of controversy – on secularism, the full veil, Islam or the caricatures of Muhammad -, can be tempted to take action.

Since you left the Paris public prosecutor’s office in 2018, the France did not repatriate French jihadists detained in Iraq and Syria. Some of these men or women are however targeted by arrest warrants. This policy without consequences for anti-terrorism justice?

It is a complex question. An appeal will soon be examined by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) which must rule on this subject. From a legal point of view, things are quite simple. More often than not, arrest warrants have been issued against all the nationals who are there. And when these people arrive in France, they are arrested and the courts have the means to judge them. But the problem is above all political and diplomatic.

We know that a majority of French people are opposed to the return of these people to our territory. On the diplomatic level, France has relations with Iraq but has none with Syria, which complicates matters. All that can be said is that it is a bet which is nevertheless relatively risky because everything depends on the evolution of the geopolitical situation on the spot. If the Kurdish and Iraqi authorities are able to detain all of these people for the long term, there will be no problem. But if the instability of the region leads these nationals to end up in the wild, there, indeed, there will be a significant security risk.