The black virtual reality glasses are tightly laced around the head. The thick support pads are designed to prevent impending pressure points as much as possible. With one click, the glasses wearer is in a new reality, Virtual Reality (VR) – a two-story apartment on Lake Lucerne in Switzerland. The view from the terrace is breathtaking. High mountains, green forests and the sparkling waters of the lake. Barely a head turn away is the living room, the graphics of which are reminiscent of a typical computer game.

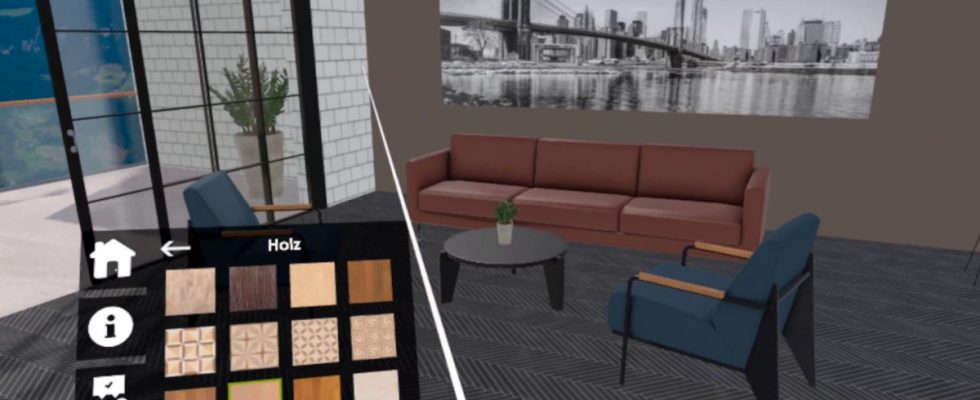

Wooden floor, brick wall, otherwise gray walls – or maybe wallpaper would fit better? With the help of two joysticks, everything can be exchanged within a few seconds, right through to the complete setup. Up the stairs, down the stairs – no problem. Only when the head moves too quickly does the edge of the picture tremble a little, which again reminds us that this is not the real world.

As part of Bau 2023, the Munich-based company HTC Vive presented the possibilities of its new VR glasses in the areas of architecture, design and construction. “We’re at the point with VR right now where we were with cell phones in 2007,” said Fabian Nappenbach, head of product marketing at HTC Vive. In short: some were already using it, others thought it was unnecessary. “But there is still a lot to come here,” he says confidently.

But how can virtual reality help with construction projects? “Customers no longer need a lot of imagination to understand plans,” says Nappenbach. You could just walk through the simulation and see for yourself. So far, the technology has been in demand primarily among kitchen manufacturers and – apart from the construction sector – also among automobile manufacturers. Is the worktop at the right height? Do the seams of the car seats match the rest of the interior? “Thanks to the digital twin, changes can be implemented live.” Another advantage of VR simulation is location independence. Builders around the world could access it through a link. This is a central element for success, especially in large projects in which a particularly large number of people are involved.

It’s not like in the cinema

That’s the theory. In the practice of everyday architects, however, it still jerks a bit. “Very few plans are that far,” emphasizes Julia Behm from the Munich architects’ office Behm.Maasberg. In order for a room to appear photorealistic and for builders to be able to try out different colours, materials and finishes, many details have to be built in. “You sit there for a few hours,” admits the 42-year-old frankly.

In her architect’s office, every plan is worked out three-dimensionally, but the VR glasses are rarely used, “rather as a toy on the side”. Behm estimates that in one in ten projects, the customer wants to examine the plan through VR glasses. “But that’s more for professional builders than private ones,” she says. Many customers who are building for the first time have wrong expectations of the three-dimensional constructions. “They think they put on the glasses and what they see looks like it’s in the cinema, it’s a 3-D film. But they can’t afford it.” One is still a long way from a one-to-one representation.

Nevertheless, Behm finds the use of the technology fundamentally sensible. “It encourages communication,” she says. “In this way, builders can compare their ideas before implementation and possible changes can be implemented by the planners.” Although this involves greater effort for the architects, there are no longer any surprises when it is completed. Its use makes sense above all when sampling large office buildings; in the case of condominiums, on the other hand, it is rather rare. “I can hardly imagine that anyone would pay for the extra effort.” After all, builders would have to reckon with additional costs of around 1000 euros for a single-family house that has already been planned in 3D.