How far the festival has progressed can be seen from the small wall of the terrace café. It is located in front of the entrance of the monumental Palazzo del Casinò, where the films are shown, and like this one it is made of light travertine stone. In the meantime, however, the glistening white has been covered with a pattern of dark spots – traces of espressos that have fallen over or been spilled. Who even his during the break coffee ristretto can’t hold on any longer, one thinks, must have been pretty shaken up by the festival films in Venice.

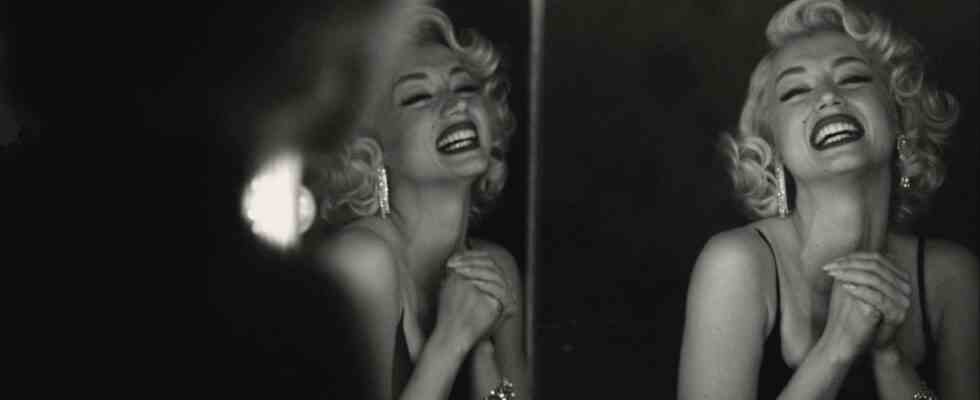

One of these shake-up films is certainly “Blonde”, the film adaptation of the novel of the same name by Joyce Carol Oates, which was released around the turn of the millennium. Australian director Andrew Dominik (“Killing Them Softly”) worked for ten years to film this massive 900-page work, after all Netflix financed him a more than three-hour film. The book, like the film, is about fathoming the mystery of Marilyn Monroe – and doing so so profoundly and empathetically that it is as if the reader or viewer were allowed to slip into her head. The fact that the facts are not necessarily all correct – how should they be with this approach – is part of the deal, so to speak.

Marilyn and President Kennedy: The author imagined this being together as a porn

But then again, you forget that because Ana de Armas as Marilyn – like the original herself, of course not a real blonde – is really convincing. And because the historically known secondary characters – Billy Wilder, Arthur Miller or John F. Kennedy, for example – all look very much like themselves. In addition, the main character Marilyn has been exposed to the most severe abuse since early childhood days, which continues seamlessly in the film industry. So is this simply Hollywood’s most famous “Me Too” story, finally told in a contemporary, i.e. brutal, clarity?

That can be very good, and it creates a strong pull, especially since everything really has a tragic ending. But then you have to tear yourself away and remember that when Marilyn Monroe was alone with President Kennedy, for example, nobody was there. Whether he was on the phone the whole time he had sex with her, whether he humiliated her and treated her like the last whore, no one really knows, not even Joyce Carol Oates, who imagined it like this – like a porn scene. And so, paradoxically, the film is both an attempt at understanding and a new round of exploiting Marilyn at the same time.

But the shaking really starts when the two competition films from Iran start in the finale of the festival. Both are running, it was already known in advance, without the permission of the Iranian authorities in Venice, and they could not come at a more critical time – in the homeland of the filmmakers, a new wave of repression against artists and directors is currently going on, which surpasses everything that has gone before. Jafar Panahi, who has been fined many times and has been banned from working and leaving the country, is currently back in prison – he wanted to protest against the arrest of colleagues and never came back.

So it was all the more astonishing that he was still able to finish his secretly filmed new work “Khers nist / No Bears” and send it to the Lido. He’s already managed to do something like this at several festivals, and so far these films have always shown himself how he remains calm, how he outwits the bans, how, despite everything, he manages to smuggle gripping stories out of his country with irony and shrewdness. Also this time you can watch him in such an action. He stayed with ordinary people in a remote village near the Turkish border to direct remotely via a mobile data connection for security reasons – his script being directed by an assistant in a nearby town.

The Iranian directors show that their country is in danger of sinking into the depths of darkness

Unlike usual, however, people’s fear is now palpable – you can feel the leaden pressure of a police state in which anyone can be arrested, and among the younger generation the desperate will to leave the country. Such an attempt to escape, told as a film within a film, goes tragically wrong, while Panahi is confronted with superstitions and family feuds in his village of refuge before he has to flee from the advance of the Revolutionary Guards – here, too, everything takes the worst possible turn. In the end, he runs out of gas alone in his car in the mountains – a tragically apt symbol for a fighter who has apparently used up his last reserves of irony and cunning.

This last shot makes you think of Panahi in his prison cell – and it is in such a cell that the second Iranian film begins: “Shab, Dakheli, Divar / Beyond The Wall” by Vahid Jalilvand. Jalilvand has also experienced repression. As one of the best-known moderators, he was banned from Iranian radio in 2014 and has been making feature films ever since. So far they haven’t been explicitly political – like “A Moral Decision”, a powerful study about responsibility and guilt. In view of the desperate mood in the country, however, Jalilvand has now given up all restraint.

“Beyond The Wall” tells the story of two people whose fates intersect at a protest demonstration that is violently and brutally put down. A young woman is arrested and separated from her very young son, who is lost in the crowd. Her desperate screams shake the entire van full of prisoners as she is driven away. Until the driver can’t take it anymore – he’s the second in this involuntary union.

When he wants to stop, a policeman grabs his steering wheel. In the accident that follows, he is almost completely blind, but the woman manages to escape. How she then meets him again in new danger, but still with the old bloodstains on her forehead – one quickly realizes that this no longer follows any realistic logic, but is part of a horrible dark dream, full of bloodcurdling wails and endless repetitions.

If the hopelessness in which the two Iranian films end is actually an indicator of the mood in the country, then Iran is on a path into deep darkness. The ideas for these films came about at least a year or two ago, cinema is not a fast news medium. And yet Panahi and Jalilvand seem to have sensed what was to come.