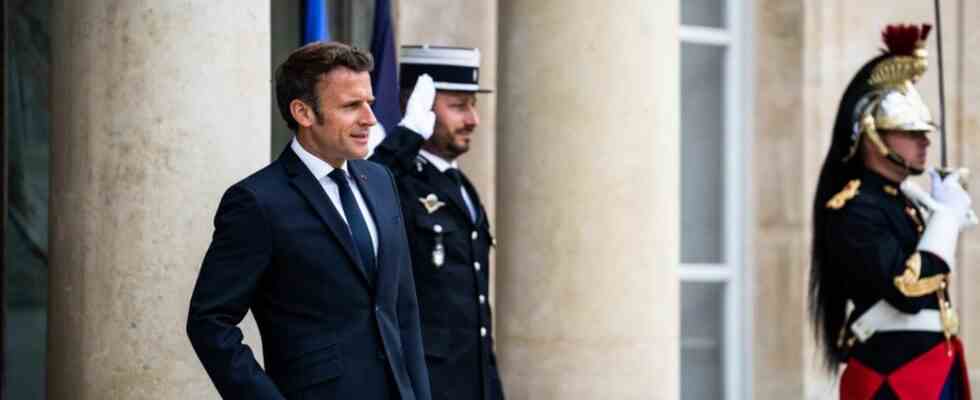

“We must collectively learn to govern and legislate differently.” During his speech to the French, Wednesday June 22, Emmanuel Macron declared to have taken note of the “fractures” who “are reflected in the composition of the new Assembly”. The President of the Republic, who lost his absolute majority in the legislative elections, said he was ready to “building compromises” with his political opponents, right and left.

>> Reshuffle, National Assembly… Follow all the political news in our direct

“As in most Western democracies, whether it is Germany, Italy, many others, no political force today can make the laws alone”, he noted. Is the Head of State telling the truth or “fake”? If he mentioned Western countries, Emmanuel Macron cited European examples. Franceinfo therefore offers you an overview of the political functioning of our closest neighbors.

The specialists interviewed by franceinfo agree with Emmanuel Macron on this point. “We can consider that, apart from the United Kingdom, all European democracies are indeed governed by coalitions”says Marie-Claire Ponthoreau, professor of public law at the University of Bordeaux.

This practice is partly due to the method of appointing parliamentarians, adds political scientist Olivier Costa. In France, the first-past-the-post two-round ballot traditionally favors the emergence of a clear presidential majority. Conversely, “in almost all European countries, the voting methods are either entirely proportional, or partly proportional with a dose of majorityanalyzes the CNRS research director at Cevipof. It is therefore very rare to have a single political force which has an absolute majority.”

“The typical example is really Germany.”

Marie-Claire Ponthoreau, professor of public lawat franceinfo

Coalitions are the hallmark of the political system across the Rhine. Since the end of the Second World War, the country has only had a government made up of a single political force for fourteen months, between 1960 and 1961. It was the CDU, the centre-right party. right. The current government of Chancellor Olaf Scholz relies on a so-called “traffic light” coalition, bringing together the Social Democratic Party (SPD), the Liberals (FDP) and the Greens.

In Germany, the construction of alliances involves the signing of a “coalition contract” between the parties. The current document, presented in November, has 177 pages (PDF in German) and sets the government’s roadmap. “It is a text which presents in an extremely detailed way the program on which the political parties agree, so as to avoid future conflicts”, explains Olivier Costa. The text provides, among other things, for the exit from coal “ideally” by 2030, an increase in the minimum wage or the legalization of cannabis consumption.

In Scandinavian countries, the culture of compromise and alliances is also widespread. In Finland, Prime Minister Sanna Marin leads a coalition of five left and center parties, reports The cross (article subscribers). In Sweden, the Social Democrats frequently rely on the support of the Left Party or the Greens, and more occasionally on the Center Party. This is generally case-by-case support, sometimes with broader agreements on specific topics.

Other countries, less familiar with the culture of compromise, have been forced to form coalitions in the face of the changing political landscape. In Spain, the People’s Party, classified on the right, and the Socialist Party (PSOE), on the left, have long alternately had an absolute majority. The bipartisanship was shattered at the end of 2015 with the breakthrough of the liberals of Ciudadanos and the radical left party Podemos in the legislative elections.

Socialist Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez ended up agreeing in 2019 with Podemos to form the first coalition government since the death of dictator Franco in 1975 and the restoration of democracy. This does not exclude recurring tensions, for example on the recent labor market reform. The coalition remains fragile, since it does not have an absolute majority in Parliament. It must therefore constantly forge alliances with the other parties in order to pass the laws.

Do these alliances weaken the stability of governments and encourage immobility among our neighbours? Not necessarily, according to specialists. In Germany, for example, the coalition contract makes it possible to ensure overall stability.

On the other hand, Italy is often considered as “the champion of instability”, notes Olivier Costa. Since the post-war period, the country has known on average a new government each year, explains François Beaudonnet, editor-in-chief of the European editorial staff of France Télévisions. The appointment of the Prime Minister is often a headache and sometimes leads to the use of a “providential figure” on which a compromise is based. “Today, Italy has united around the unifying figure of Mario Draghi”illustrates Marie-Claire Ponthoreau.

In these countries accustomed to coalitions, the formation of governments can also take long weeks, even months. After the legislative elections of May 2019, Belgium waited sixteen months for a coalition of seven parties to agree on the composition of a majority government. “It does not mean that the country does not have a government during this time, since the resigning government is responsible for expediting current affairs”nuance however Olivier Costa.

Finally, it remains to be seen whether such a system could be transposed to France. In theory, the Constitution of the Fifth Republic, dating from 1958, established a parliamentary regime. In practice, the election of the President of the Republic by universal suffrage from 1962 and the five-year reform in 2000 strengthened the position of the Head of State. In this context, the parliamentary character of the system has become less important, as detailed on the public-life site.

“However, the cohabitations have shown that the Constitution is plastic. It could therefore adapt very well to the situation we know today.”

Marie-Claire Ponthoreau, professor of public lawat franceinfo

“The unknown is rather the ability of political forces to negotiate and try to come to an agreement”continues Marie-Claire Ponthoreau. “We are in a mixed regime, both presidential and parliamentary” where “compromise is experienced as a compromise”, analyzes political scientist Pascal Perrineau. For now, discussions between the Prime Minister and the various political parties to form a coalition government are stalling.