Almost 1,200 people, at least according to the plans of the builders in 1941, could find shelter in the high-rise bunker on Blumenstrasse. So 200 on each of the six floors. On this June evening there are around 60 visitors sitting on small stools on the first floor, some have to stand. Anyone who has never been here will be overcome by an oppressive feeling of confinement in this windowless, squat room. Instinctively you move crouching, pull your elbows close to your body and spot the ventilation system on the ceiling. What a place to encounter Francisco de Goya’s “Los Desastres de la Guerra”.

This hard-hitting series of graphics, first published in 1863, in which the artist depicts the universal loss of all humanity in war. Brilliantly erased, abysmal and in the end without any hope that human nature will ever change. An exhibition in the former Munich air raid shelter shows that Goya was only too right with his nihilism. Amazingly, a red thread from the world-famous “Disastres” cycle, which arose during Napoleon’s occupation of Spain, leads directly to the war in Ukraine. Refugee Ukrainian women used the embroidery needle with virtuosity.

“Rushnyk – Desastres de la Guerra. Pictures of War and Peace” is the name of the show in the Klotz near the Schrannenhalle, which is now one of the most interesting cultural venues in the city. The Architekturgalerie München has rented it and has been converting this very special building, which has no heating and no foyer, into a veritable art space since 2016. It was also the history of the building that gave the Bavarian State Opera the idea of choosing the bunker for their “Rendezvous! Number 4”. A series of events with this somewhat old-fashioned, lovely name, which loosely ties in with the respective season premieres and takes the audience to places away from the usual venues. The bunker was an obvious choice for Sergei Prokofiev’s monumental opera “War and Peace”, which was put on the program long before the outbreak of the Ukraine war.

Bed storage in the shelter? Director Dmitri Tcherniakov stages Sergei Prokofiev’s monumental opera “War and Peace” at the Bavarian State Opera in a claustrophobic room, in the hall of the House of Trade Unions in Moscow.

(Photo: Wilfried Hösl)

As is well known, the opera project was a crucial test for the State Opera in view of global political developments, which pushed director Dmitri Tcherniakov and general music director Vladimir Jurowski to their limits. But the result (première in March) was, in Goya’s spirit, an urgent plea against war. The scenic also plays in a claustrophobic room, the hall in the House of Trade Unions in Moscow, into which people have taken refuge.

Know each other from studying architecture at the TU Munich in the nineties: Nicola Borgmann, head of the architecture gallery, and artist Caro Baumann (from left).

(Photo: Saskia Wehler)

Nicola Borgmann, head of the Architekturgalerie, could not have known about this dramaturgy more than a year ago when the request from the opera for the rendezvous came and she enthusiastically agreed. But between the 1.30 meter thick bunker walls, music by Ukrainian composers should not only be heard once, like last week at the vernissage. Borgmann wanted to use the “War and Peace” rendezvous as an opportunity for a special exhibition. And she thought of her friends Caro Baumann and Johannes Schele, two artists “who carry a convinced pacifism within them.”

A city at peace? Artist Johannes Schwele photographed views of Kiev during a lecture tour in 2010, on a car-free Sunday, almost four years before the Maidan protests.

(Photo: Saskia Wehler)

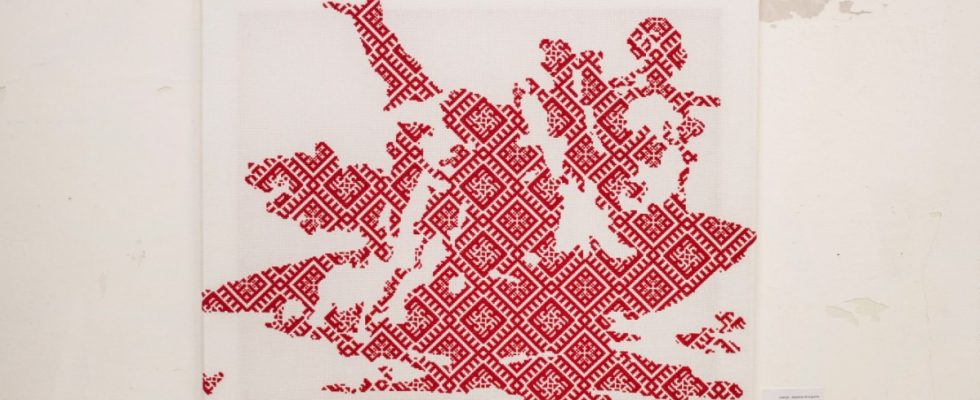

Baumann and Schele (on the second floor of the bunker, alienated photographs of a Kiev in peacetime can be seen) founded the “morePlatz” office while they were studying architecture at the Technical University of Munich in 1997 and now work from Berlin. It was also in Berlin that Caro Baumann came across the Rushnyk Museum in Kiev while researching Ukraine on the Internet a few days after the start of the war. On display there: traditional embroideries in red and white with elaborate, strictly geometric patterns, which in the Ukraine mostly adorn rite cloths for births, baptisms, weddings and funerals. Baumann was fascinated, especially since she had worked with embroidery herself years ago. When tracing the Rushnyk ornaments, she spontaneously had Goya’s “Los Desastres de la Guerra” in mind and came up with the idea of depicting these terrifying images using the old Ukrainian embroidery technique.

Some works consist of up to 50,000 cross-stitches, all embroidered by hand over months by Caro Baumann and the Ukrainian women.

(Photo: Saskia Wehler)

“The superimposition of the two art forms creates a kind of interaction,” says Baumann. In fact, one should look at these pictures from a certain distance, then Goya’s human slaughterings become apparent like rough silhouettes. It seems, at least that’s how Baumann feels, as if the two art forms are mutually destroying each other. The strict order of the Rushnyk pattern is broken up by the stencil-like quality, while the clear geometry of the cross-stitches breaks down Goya’s virtuoso stippling technique in aqua tinta. An embroidery image can have up to 50,000 stitches. In Berlin, Baumann found women who had fled from the Ukraine – among them Anna Babenko, Elena Dyhalo, Olena Shu and Ksenia Sobotvych – who still mastered this complex technique. She then sat with them for months on the pictures. A meditative work that brought her closer to the fate of women and helped her to overcome the feeling of her own helplessness.

The choice of exhibition location gives these already haunting works an additional depth. One sees people standing in shelters, as they have always done, and stoically desperate – to distract themselves and others from the omnipresent fear of death – doing one cross stitch after the other. With a red thread.

“Rushnyk – Desastres de la Guerra. Images of War and Peace”until 6 July, Mon – Fri, 12 p.m. – 6 p.m., Munich Architecture Gallery, Blumenstraße 22, access via the listening room on the square in front of the bunker, Information at www.architekturgalerie-muenchen.de