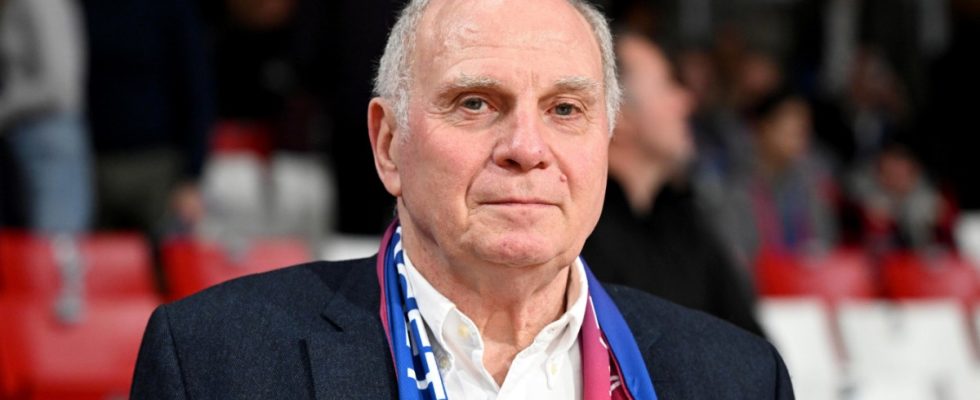

From time to time things get moody in the Frankfurt regional court. For example, when Uli Hoeneß explains why his FC Bayern played friendly games in distant countries for a fee of a few hundred thousand marks before the 2006 World Cup was awarded, and why the club’s economic situation had improved so much that it was for them The amounts from back then would no longer be possible today.

The remark on the tip of your tongue is that revenue may be lower this year, says presiding judge Eva-Marie Distler the day after the title decision in favor of Bayer Leverkusen. He had to disappoint them, the Bayern patron replied, saying they had a great year, even if Leverkusen rightly became champions. But he heard that the judge was a fan of Eintracht Frankfurt – she was having a difficult time there.

In fact, Distler is not only a fan, but also a member of Eintracht’s board of directors. But apart from such humorous interludes, it is a very serious conversation that takes place on Monday afternoon in the Frankfurt Justice Center. Hoeneß testified for almost 90 minutes in the tax trial about the unexplained million-dollar scams surrounding the 2006 World Cup and the then World Cup boss Franz Beckenbauer. His core message: He doesn’t know the purpose of the mysterious ten million francs that ended up with Qatari scandal official Mohammed bin Hammam in 2002 and for which Beckenbauer received a loan from entrepreneur Robert Louis-Dreyfus. But the theory that this was used to buy votes for the award of the World Cup was “absurd”.

Hoeneß’ appearance certainly provides fuel for the process

Hoeneß is on the witness stand because he publicly stated a few years ago that he “knew pretty well what was going on back then.” Now the judge is accusing him of saying that what he is saying is not “pretty accurate,” but rather roughly to nothing at all. And yet Hoeneß’s appearance provides fuel for the process in many respects.

For example, the Bayern patron described why he even whispered on a TV show and in a podcast that he knew so much about the matter. Hoeneß was good friends with Louis-Dreyfus for many years, and at one of the many meetings the ten million issue was casually discussed – sometime between 2005 and the entrepreneur’s death in the summer of 2009. Louis-Dreyfus made fun of “the fact that the DFB wasn’t man enough” in connection with the organization of the 2006 World Cup and “had to answer for a demand of ten million Swiss francs.” The DFB promised him that he would get a corresponding payment back – in the person of its president Gerhard Mayer-Vorfelder. Louis-Dreyfus also made a few comments about the weakness of the DFB.

On the one hand, it is remarkable that more people in German football apparently knew about the ominous million-dollar transaction very early on than were previously known; and that at a time when Louis-Dreyfus was working diligently with the German Football Association through his newly founded television rights company Infront. It is also noteworthy that Hoeneß has now repeatedly placed Mayer-Vorfelder as a person – and thus the DFB as an association – at the center of what was going on at the time. Because this does not correspond to the details known so far.

Theo Zwanziger (left), Horst R. Schmidt (center) and Wolfgang Niersbach (sitting) are accused in the 2006 World Cup trial.

(Photo: Arne Dedert/dpa)

Only hours before Hoeneß’ appearance did the court read out the statements that Franz Beckenbauer, who died in January, had made in preliminary proceedings in Frankfurt and Bern. And Mayer-Vorfelder played no role in his lectures, Distler now accuses the witness. Hoeneß says he can’t imagine that a president knows nothing when it comes to such elementary things. “It’s like FC Bayern buying a player for 50 million euros and I don’t know anything about it.”

That a president doesn’t know such things? Hoeneß can’t imagine it.

Hoeneß’ comments are also interesting about a second person: Robert Schwan, Beckenbauer’s long-time manager. Because Hoeneß emphasizes that the ten million question was “a demand from Robert Schwan” – and that Louis-Dreyfus’ interlocutor for the loan was Schwan. The strange thing about this version is that when Louis-Dreyfus stepped in as a lender, Schwan was no longer alive.

The story of this strange and complicated million-dollar carousel began in May 2002. At that time, the first six million flowed from a Beckenbauer account via a stopover in Switzerland to bin Hammam in Qatar; The official reason for payment was the acquisition of TV rights to the Asian Games. Schwan died in July, and it was only in August that Louis-Dreyfus’ bank discussed that its customer needed fresh money: as a lender for the six million that had already been paid and another four million that were still outstanding, which were also flowing to Qatar.

Louis-Dreyfus then had to wait two and a half years for repayment until 6.7 million euros went to him from the World Cup organizing committee’s coffers via the world association Fifa to repay the loan. And now the three former DFB officials Wolfgang Niersbach, Horst R. Schmidt and Theo Zwanziger are in the dock because they are said to be responsible for the fact that these 6.7 million euros were wrongly declared as business expenses in the tax return.

The judge cannot fully understand why Hoeneß allegedly knows nothing about the intended use. She asks whether he is not a curious person at all and whether he did not inquire in his conversation with Louis-Dreyfus. No trace, Hoeneß replies – and besides, he never spoke to Beckenbauer about the whole matter. “It was a taboo topic,” he says. But that doesn’t stop him from definitely ruling out some uses. Not just the vote-buying variant, which Hoeneß does, among other things, with the argument that he knew Louis-Dreyfus well and that he never granted a loan for something like that. But above all, the hottest lead in this complicated affair: that the payment should be seen in the context of a television rights deal.

Like many other things, this is indicated by the note “Asian Games” in the transfer slip. But no, Hoeneß doesn’t want to hear anything about it. “You can write a lot in there to possibly mislead the people who are investigating it afterwards,” he says to the judge: Instead of the Asian Games, it could have been called the Alaska Games. Schwan was a down-to-earth Bavarian person and not a polyglot type who bought television rights all over the world. “You can forget all these fairy tales”.

But sometimes, says Judge Distler, “fairy tales have a grain of truth.”