When he climbs, Andreas Gramsch doesn’t just defy gravity. He also fights for a better life for people with intellectual disabilities. The 34-year-old lives with an autism disorder and wants to aim high at the Special Olympics.

By Sophia Klimpel Akahoshi

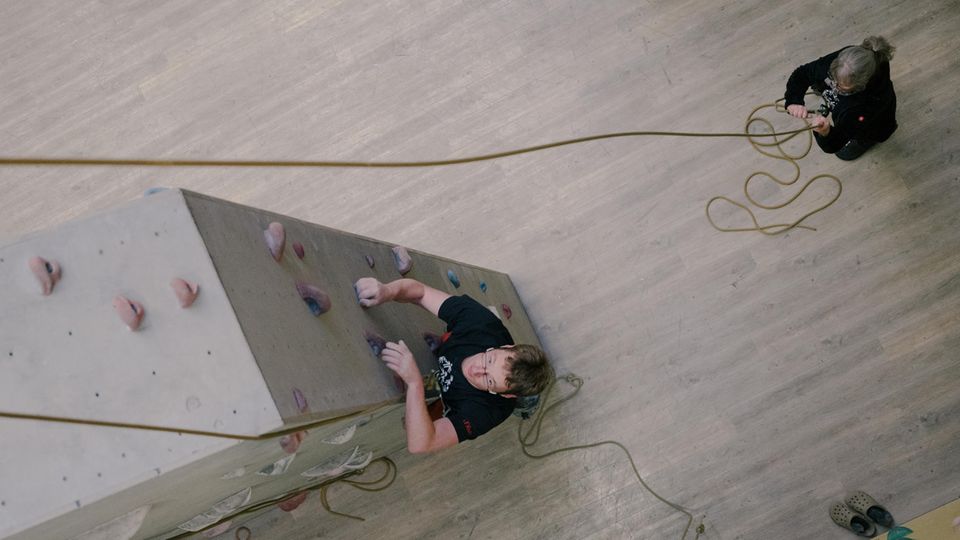

“What are your hands doing?” asks Gabi while Andreas studies the colorful handles on the gray wall. “A little blue, right?” And indeed: Andreas’ hands are ice cold, his fingers grey-blue. It’s freezing outside on this December afternoon. The puddles on the sidewalks freeze and a frosty wind blows through the climbing hall.

Andreas, however, doesn’t mind the cold. He barely feels them, even when his body is cold.

He lives with cognitive impairment with autism disorder, perceives some things differently than many of his fellow human beings and feels physical pain less strongly. He doesn’t like to break out of his usual patterns and social interactions with strangers are often difficult for him.

His mother Gabi supports him in all of this. She helps with complicated climbing knots, reminds Andreas to pay attention to his own body and shows him warm-up exercises. The 34-year-old spends several hours three times a week in the climbing hall in Mülheim an der Ruhr.

He has big plans, as his T-shirt shows. “Special Olympics North Rhine-Westphalia” is written on it in white letters, the fabric hardly has a wrinkle. For Andreas, these words mean the final spurt: in just a few weeks he will be competing at the largest inclusive winter sports event in Germany.

Does the dizzying height ever make him nervous? “Sometimes I used to,” admits Andreas. But he has long since gotten used to it

© Katharina Kemme

900 athletes test their strength at the Special Olympics

Special Olympics is a global inclusion movement for people with intellectual and multiple disabilities Disability. The organizers believe that the games have a mission: they are intended to help people with intellectual disabilities gain greater recognition, self-confidence and social participation. There are training offers for everyone, further education courses, competitions.

The next one starts on January 29th in Thuringia. At the National Winter Games, 900 athletes compete against each other in ten disciplines. Climbing is taking part for the first time this year. Andreas will test his strengths against 85 other athletes.

The sport has so far been missing at international level. It’s a shame, says Andreas, after all the athletes from other disciplines at the National Winter Games qualify for the 2025 World Winter Games in Turin. If climbing ever becomes part of these international games, his dream will grow with it.

Marcus takes care of Andreas’ mail, Matthias cooks his meals

Andreas is a triplet, the middle one. His brother Thomas is a minute older than him, Marcus a minute younger. Both are a head taller than Andreas and have full beards. Matthias, the “singleton,” as his mother Gabi calls him, was born six years after them. They all live in the same house and know what to do to support the athlete in everyday life.

Magnesium powder prevents his hands from slipping off the holds: Andreas rubs them with it before every climbing tour

© Katharina Kemme

Thomas and Gabi climb with Andreas. Marcus takes care of his mail and plays badminton with him. Matthias cooks Andreas’ meals and is his second guardian if Gabi is unavailable. Because even the worst case scenario is taken care of, must be taken care of: “Now the time has come when I have to remember that at some point I won’t be there anymore.” Gabi says this matter-of-factly; like so many things, she approaches the topic strategically.

Many years before the triplets were born, she was a teacher at the Hünxe Forest School, a school with a focus on intellectual development. “I would have looked stupid with triplets and a child with a disability,” she says. “If it weren’t for my professional background.”

“We always lived to a certain extent in the gym”

Not only did Andreas always have his triplet brothers by his side, the sport was also there from the beginning. Shortly after the triplets were born, Gabi founded her own parent-child sports group and dragged her boys to children’s gymnastics, to badminton, to climbingand for fencing. And of course to judo, after all, she had been a judo trainer herself for years.

“We always lived to a certain extent in the gym,” says Gabi with a laugh. Andreas is also a judoka and has made it to a black belt. For several years he was on the athletes’ council of Special Olympics Germany and traveled across the country to compete in Holland, England and Japan. In 2019 he won the silver medal at the Special Olympics World Games in Abu Dhabi.

He’s proud of that, says Andreas in brief words. At some point the time was ripe for something new. In judo he finally achieved everything he set out to do. So now climbing.

Andreas had a choice: a workshop for the disabled or the first job market

The World Health Organization defines intellectual disability as a “significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information and to learn and apply new skills.” This limitation begins before adulthood and has lasting effects on a person’s development.

According to the organizers of Special Olympics, around 200 million people worldwide live with an intellectual disability, 320,000 of them in Germany – a number that is based on estimates, as intellectual disabilities are not statistically recorded in Germany.

Around eight percent of them are active in sports, also because those affected have to overcome high hurdles. The organizers say that public sports facilities are often difficult to access, stigma is widespread and training staff are not adequately trained.

Not only in sport, but also in other areas of everyday life, people with intellectual disabilities repeatedly come up against structural limits: for example in the labor market. The JOBinclusive initiative criticizes that in many companies there are prejudices against mentally disabled people, who therefore hardly find a job on the primary labor market. However, the qualification opportunities in special facilities were far from enough to give oneself a fair chance. A vicious circle.

Today, Gabi laughs when she talks about her early days in the painting business

Like many of those affected, Andreas and his family were faced with a choice: workshop or first job market. They chose the latter more than 16 years ago.

When Andreas talks about his job today, he talks about “fulfillment” and feeling “appreciated.” He works in a painting company, cleaning used tools, sorting them and arranging the brushes and paints so that his colleagues can work quickly with them. 20 hours, every week.

He got to know the painting business through a school internship; the owners are old family friends of the Gramschs. “That worked well,” remembers managing director Oliver Lemm.

Andreas’ learning phase took a long time. First he tried out different areas and even went to the construction site. However, working there wasn’t for him. Too busy, too restless.

Another time he forgot the time in the evening and stayed in the warehouse after the store closed. There the motion detector detected him and informed the police – a big shock for the Gramsch family: “Andreas didn’t come home in the evening, so I drove to the company to look for him. And found the police instead.”

Today, Gabi laughs when she talks about her early days in the painting business. Also because the effort was worth it. Andreas has long been an established part of the company, and Lemm and his colleagues appreciate his conscientiousness. His next goal: to get a forklift driver’s license so that he can lift the paint pots onto the boards of the meter-high shelves.

Andreas climbs, Gabi belays. Every now and then she points out handles to him. But most of the time she stays silent while her son climbs up the walls

© Katharina Kemme

“Open and close. Open and close.” Gabi’s hands dictate the movements, Andreas repeats them until his fingers are pink and comfortably warm.

Then they check together whether the figure eight knot with which he attached the rope to the climbing harness is tied correctly. Whether the carabiner that holds the belay device to Gabi’s belt is securely closed.

Gabi raises her right hand, Andreas his left. First their palms clap together, then their clenched fists. Finally Andreas starts climbing, Gabi belays.

The fingers of his left hand grasp a purple handle. Those on the right the next. Then he drags his feet and now stands on the narrow steps. He climbs calmly and composedly, pausing patiently as he searches for a new hold.

He’s in no hurry. The main thing is that it goes up.

Transparency note: RTL Deutschland is part of the media alliance of the Special Olympics National Games Thuringia. At Germany’s largest inclusive winter sports event, around 900 athletes will compete in ten sports from January 29th to February 2nd, 2024. Like stern, GEO is part of RTL Deutschland.