The face is emaciated, the nose long and pointed. The woman has closed her big eyes and listens to herself. She is pregnant, her arms lie protectively on her round belly. A gesture that is immediately touching in its simple grace.

At first sight, it is not surprising to encounter a figure by Emy Roeder in the collection rooms of the Würzburg Museum in the Kulturspeicher. Finally, the Municipal Collection owns the extensive estate of the Würzburg native and extraordinary modern sculptor. But the way the portrait of the “pregnant woman” made of walnut wood by Roeder shortly after the First World War is currently being shown in the large special exhibition “The Rescue of Evil”, which is spread over two floors, has certainly not been seen before.

On the brightly lit side of the first of three exhibition rooms, it is surrounded by works by the sculptor Elsa Sahal, who was born in Paris in 1975. On the other hand, on the opposite side, which is almost completely immersed in darkness, are drawings by the Würzburg painter Ferdinand Spiegel, a dubious figure in the Nazi art elite. A greater contrast is hardly imaginable.

Elsa Sahal’s ceramic sculptures no longer depict the female body as a unit, but as a deconstructed piecework. Bizarrely bent feet and exaggeratedly elongated breasts form a never-before-seen bundle of corporeal power that playfully celebrates being a woman. A pleasingly life-affirming view that has something archaic as well as anarchic about it and brings Emy Roeder’s aesthetic positions into the present. In her art, Roeder aimed for the unity of expression and form, thereby paving the way for subsequent generations to abstraction. Her figure of the “Pregnant Woman” from 1920 shows this impressively.

The female body as patchwork: Elsa Sahal’s work “Trukula Baubo” from 2015.

(Photo: Hans-Georg Gaul/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022)

But that made Roeder a thorn in the side of the Nazis. In 1937 they confiscated the terracotta version of their “pregnant women” and displayed it in a defamatory manner in the “Degenerate Art” exhibition. Fortunately, Roeder was already abroad at the time and was only to return to Germany in 1949.

Anyone who knows about this background can guess why the exhibition curator Michael Müller confronts the sculptures by Roeder and Sahal with designs by Ferdinand Spiegel of all things for the Berlin Reichsbank building, which was built in the 1930s. In their purest form, they show a completely different image of women: heroines with blond hair, angular faces, and ice-cold eyes.

The drawings come from Spiegel’s estate, which also found its way into the municipal collection after the Second World War. A poisoned legacy that the current museum management of the collection founded by the Nazis in 1941 has to face again and again. This happened ten years ago in the exhibition “Tradition and Propaganda”. Then the provenance research was started.

“The Rescue of Evil” is the attempt by museum director Luisa Heese to deal with the burdened past of her institution not in a scientific but in an artistic way. She invited the Berlin-based German-British artist Michael Müller, who had previously brushed the collection of the Städtische Galerie Wolfsburg against the grain.

Emy Roeder’s art was defamed by the National Socialists. Here her work “Naked boy lifting a child” from 1928.

(Photo: Andreas Bestle/MiK)

Behind the motto “Present and absent shadows”, which the 52-year-old chose for the first part of the exhibition, is the controversial question, which is currently being asked in many art collections, of how we should deal with Nazi art today. Should it be shown at all? If yes how? Or should you just let them gather dust in the depot? The book “The Long Shadow of the Past” by Aleida Assmann, in which the renowned English scholar reflects on our culture of remembrance, spontaneously comes to mind as you walk around.

What was originally planned by Michael Müller as a manageable intervention in the collection rooms grew over time into a complex special exhibition about evil itself. It now also includes works by Albrecht Becker through Andy Warhol to Gerhard Richter and demands a lot from the viewer. Above all, Michael Müller’s own installations, with which he reacts to the artists mentioned in parts two (“Compare >, =”) and three (“Possible and impossible images”), directly involve the visitors. In his work, for example, mirror surfaces appear again and again, in which one inevitably encounters oneself.

For Müller, it is always we humans who stigmatize and exclude, imprison and kill other people

The terribly cryptic title “The Rescue of Evil” makes sense if you don’t take it literally. But as an invitation to face evil. Even if many would like that because it has a relieving effect: Evil does not exist outside of us. In the words of the performance artist Ana Mendieta, who died under unexplained circumstances and who quotes Müller at one point: “There is a devil inside me.”

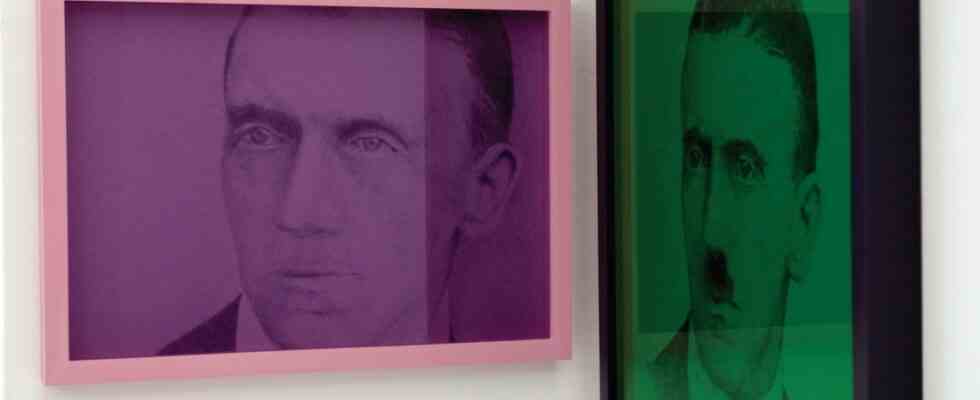

Müller’s 2010 work “There are no monsters”, for which he drew Hitler once with and once without a mustache, is central to the entire exhibition. The artist thus opposes any form of mystification of evil. Instead, he sticks with Hannah Arendt and her famous dictum about the “banality of evil”.

Müller also guided this in his examination of Gerhard Richter’s “Birkenau Cycle”, which occupies the entire third room. In his 16-part installation “Possible and Impossible Images” from 2022, Müller takes a stand against Richter, whom he accuses of having turned the Holocaust into a nebulous event. However, this makes it impossible to say specifically what really happened back then.

For Müller, it is always we humans who stigmatize and exclude, imprison and kill other people. All of his works have an ethical element that runs like a red thread through the multi-faceted show.

Michael Mueller: The Deliverance of Evil/Possible and Impossible Images. Museum in the Kulturspeicheruntil March 19