Dreamy, tired, absent. So on a Monday morning you can meet a lot of students, including in grade 6a at the Maria Ward Girls’ Secondary School in Schrobenhausen. But instead of being sent straight to math or English class, the students sit comfortably in a circle with their class teacher Ulrike Neumair; the ritual is called “encounter with the world”. The center is decorated with a Bible, colorful cloths or a green balloon with a laughing face.

Today the class starts class with The Walk to Emmaus, a biblical story. But other topics are also common in the morning circle: current news from the world and the city or personal matters. This “world encounter” takes place for all classes and is part of the Afra concept of the school system of the Diocese of Augsburg. The girls’ school in Schrobenhausen applied for the German School Prize on behalf of all of the foundation’s facilities; and thanks to the concept, it is now one of two Bavarian schools in the final round.

Student-teacher relationship is crucial

Afra, on the one hand, stands for the patron saint of Augsburg, and on the other hand, for an “alternative, caring, religious and accepting” school. The Schulwerk began planning the program about four years ago after individual schools developed components independently. They wanted to combine these in one model. Schrobenhausen started two and a half years ago as a pilot project with Afra. The focus is on the young people; the interaction between the teacher and the children should be familiar and close. “I am convinced that the relationship between students and teachers is the basic ingredient of a successful school,” says Peter Kosak, director of the school in Augsburg.

Peter Kosak is director of the Augsburg diocese’s school organization and believes that teachers must once again become the decisive factor in everyday school life.

(Photo: Martin Augsburger/Schulwerk of the Diocese of Augsburg)

In order to strengthen this, biology, religion, geography and history are combined in the subject network (NeWe) in the Afra classes; From the ninth grade onwards, politics and society are also added. The class leader teaches this area eight hours a week. “Unlike a minor subject with two hours per week, you get a completely different approach to the children,” says class teacher Neumair.

For 6a, a NeWe unit takes place directly after the morning circle. Four students present the biblical event of Emmaus in a role play. The class discusses together the meaning of the two disciples’ encounter with the risen Jesus. In the next few weeks, the students will look at the story from other perspectives, for example looking at how a date palm is structured (organic) and talking about where Emmaus actually is on the map (geography).

Laura, Franziska and Katrina are already in the tenth grade. All three previously attended a different school and can therefore compare the NeWe lessons with the usual teaching. “Normally, for example, in history you would do the Holocaust in February, but Judaism in Reli in October,” says Franzi. “In NeWe everything is more compact and you can imagine a lot more about the topics.” In addition, you can remember the content better because you only have to study for one subject, says Katrina.

“Substitute moms” for the little ones

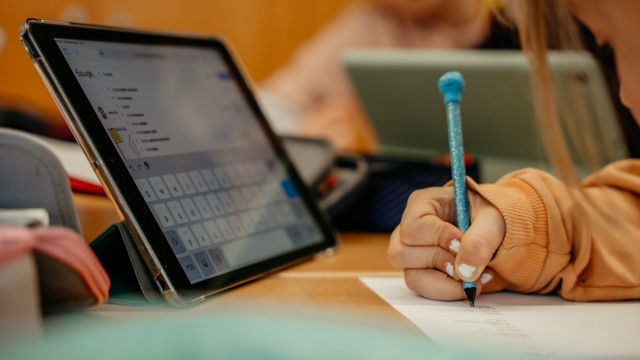

While the older girls continue to work on a project about organ donation, the 6a girls go to the digital learning workshop (DLW). All fifth and sixth graders work independently on their tasks for various subjects on their iPads. In addition to the teachers present, the children receive additional support from educational specialists. This is intended to strengthen the caring character of the school concept. Birte Schäfer is both a teacher and educational specialist in Schrobenhausen. As such, she is a “substitute mom” and “sorrow aunt”: “The little ones in particular come to us with personal problems. Many people have no one to talk to at home,” says Schäfer.

As soon as the students are finished in the DLW, they fill out their learning diaries. There you can also record how motivated you were that day. “Reflection is a central aspect here,” says Schulwerk director Kosak. “I don’t just write an ex and then the thing is over, but I make myself aware of what I’ve learned.”

In the digital learning workshop, the fifth and sixth graders at Maria-Ward-Realschule complete tasks for math, German, English and NewWe or a minor subject.

(Photo: Schulwerk of the Diocese of Augsburg)

The four Cs (communication, collaboration, creativity and critical thinking) are central to this, with which young people should be able to assert themselves better in the modern job market. The four-C model for learning in a digital world spilled over from the USA to Germany in 2013, but usually plays no role here.

“If we were to test collaboration and communication in the final exams, as things stand today, that would be fraud,” says Kosak. The alternative teaching method is therefore not reflected in the grades. Nevertheless, there are advantages for Afra graduates: “Our students have a completely different standing at companies,” sums up Frank Puschner, headmaster of the Maria-Ward-Realschule. Through project work, young people would deal with problems in a more solution-oriented manner. This is noticeable during the job interview or in the assessment center.

Because of this positive feedback, the Catholic School Association would like to see fundamental changes. Christian Schwarz is the headmaster of the St. Ursula-Realschule in Augsburg. He complains that exams have hardly changed in recent decades, while the demands on young people have become completely different. “Certificates need to be described more precisely and people need to be described in words,” says Schwarz. Kosak summarizes the problem as follows: “We always act as if grades are meaningful. They are not.” The schools are trapped in this evaluation system. “With the Afra concept, we are stretching the boundaries until they are almost bursting,” says Kosak.

Whether the jury of the German School Prize considers this crossing of the line to be worth imitating will become clear when the winners are announced in the fall.