Reason for concern: In recent years, typhoid bacteria have increasingly developed new antibiotic resistance, as revealed by genetic analysis. The mutations make the pathogens immune to modern emergency antibiotics and are now spreading from India. This development is worrying, stress the researchers in the journal The Lancet Microbe. In extreme cases, this could mean that no oral remedy for typhoid fever works.

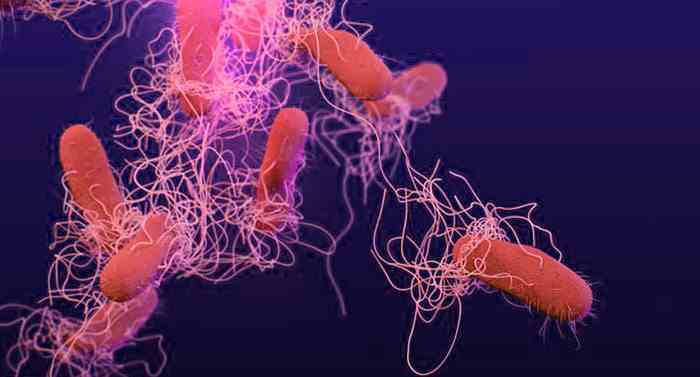

More than eleven million people contract typhoid fever every year and around 100,000 die from it, mainly in South Asia and Africa. The causative agent of this bacterial infection, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, is usually transmitted through contaminated water or food. Although the infection can be easily treated with antibiotics, strains resistant to antibiotics are increasingly spreading.

From South Asia to the world

Kesia Esther da Silva from Stanford University and her colleagues have now investigated how widespread and where such resistant and multi-resistant typhoid bacteria are now widespread. For their study, they analyzed bacterial DNA from 3,489 pathogen samples taken from South Asia between 2014 and 2019. In addition, they evaluated 4,169 other samples that came from more than 70 countries and were collected over the past 100 years.

The analyzes revealed that multidrug-resistant strains of the type pathogen that are immune to older classes of antibiotics have been circulating in South Asia for decades. They mostly originated in India and have been introduced to other countries and regions from there more than 197 times since 1990 alone, as the team reports. The most common transmissions were within South Asia or to Southeast Asia, but the resistant typhoid strains also reached Africa, North America and Europe.

New resistances on the rise

However: In the meantime, newer resistant forms are spreading in addition to these “classic” multi-resistant typhoid bacteria. They have evolved mechanisms that also make them immune to modern classes of antibiotics such as cephalosporins, quinolones and macrolides. As early as the 1990s, there were bacterial strains with resistance to fluoroquinolones. In 2010, these already accounted for 95 percent of the type specimens from India, Pakistan and Nepal, as reported by da Silva and her colleagues.

In the last 20 years, at least seven bacterial lines with resistance have also emerged against azithromycin, a commonly used macrolide antibiotic. The research team also identified several strains of cephalosporins with corresponding resistance genes. As with the early multidrug-resistant typhoid bacteria, most of these new strains developed in India.

“A real cause for concern”

“The rate at which highly resistant strains of Salmonella Typhi have evolved and spread in recent years is a real concern,” said senior author Jason Andrews of Stanford University. “This underscores the urgent need to expand and intensify preventive measures, especially in the most vulnerable countries.”

The researchers see a particular danger in the fact that the type pathogens can exchange the newly acquired resistance genes with each other. This can then result in bacterial strains that are insensitive to both older active ingredients and the new quinolone and macrolide antibiotics. “Such organisms would evade any treatment with established oral antimicrobial agents,” write da Silva and her colleagues. “This would lead to increased hospital admissions and increased morbidity and mortality.”

A global problem

According to the research team, their results are also a clear indicator that India remains an important hotspot for the emergence of antibiotic resistance – more urgently needs to be done here. “The fact that resistant strains of the typhoid bacterium have so often spread internationally also underscores that controlling typhoid fever and resistance must be seen as a global problem, not a local one,” says Andrews. (The Lancet Microbe, 2022; doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00093-3)

Source: The Lancet