Erdogan is the favorite in the runoff election for the presidency. The nationalists are already the winners. For some, the election is existential and a victory for Erdogan would have very personal consequences.

For Cansu Yapici, Sunday’s presidential election in Turkey is more than a vote on President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. She also decides whether she can see her 71-year-old mother again in freedom.

Cansu’s mother, the architect Mücella Yapici, became known ten years ago for her work against the development of the central Gezi Park in Istanbul. The 2013 protest in the park expanded into nationwide demonstrations against the increasingly authoritarian policies of Erdogan, then prime minister. He had the largely peaceful protests brutally suppressed.

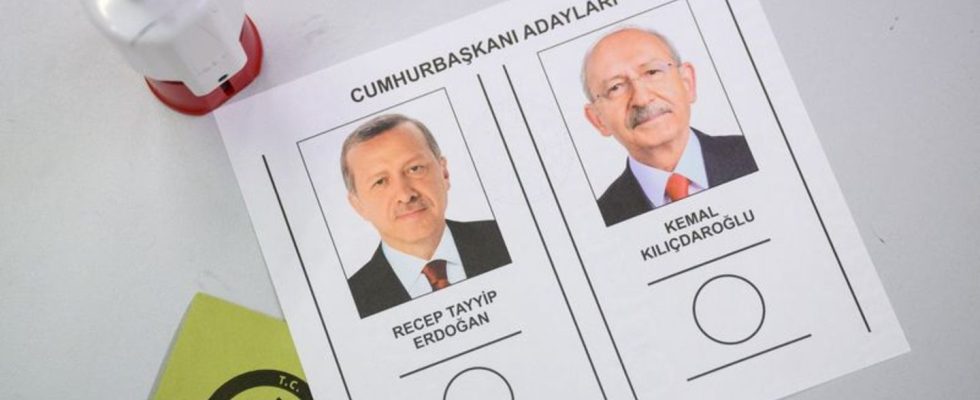

Today, numerous actors from back then are in prison, including Mücella Yapici. She was sentenced with others to 18 years in prison. Culture promoter Osman Kavala received a life sentence. The accusation: initiating an attempted coup or aiding and abetting. Human rights activists criticize the process as politically motivated. On Sunday, Erdogan will face his challenger Kemal Kilicdaroglu in the runoff – and it will be the tenth anniversary of the Gezi protests.

“The choice is existential for me”

“If we lived in a country with the rule of law, we wouldn’t have to talk about the fact that my mother’s imprisonment had anything to do with the outcome of the election,” says Cansu Yapici (35). She hopes that if Kilicdaroglu wins, Turkey will become a constitutional state again. “The choice is existential for me.”

But Yapici doesn’t have too high hopes anymore, because Erdogan is going into the race as the favourite. In the first round of the presidential election two weeks ago, Erdogan just missed an absolute majority. He received around 2.5 million votes more than his challenger Kilicdaroglu, despite numerous problems in the country such as a currency crisis. International observers rate the vote as fundamentally free, but criticized an unfair election campaign.

Behavior of nationalist voters determines election outcome

The opposition now wants to make up for the difference – according to observers, a difficult task. The third-placed right-wing candidate Sinan Ogan has meanwhile placed himself behind Erdogan. It is unclear to what extent his voters follow the recommendation, Ogan primarily attracted protest voters. However, it is taken for granted that the behavior of nationalist voters will determine the outcome of the election.

“Nationalism is the rising trend in Turkey,” says Hurcan Asli Aksoy from the Center for Turkish Studies CATS. A phenomenon that can be observed all over the world.

But Erdogan was able to contain that as well: The voters gave him a kind of setback – Erdogan’s Islamic-conservative AK party achieved its worst result since its foundation in 2002 with around 35 percent in the parliamentary elections. According to observers, however, the votes did not migrate to the opposition, but rather to the ultra-nationalist MHP, with which the AKP has governed in alliance since 2015. According to Aksoy, the election resulted in the most nationalist parliament in Turkey’s history. Nationalists are in all camps.

Support from the pro-Kurdish HDP for the challenger

Kilicdaroglu tries to score points with a six-party alliance made up of parties from different camps. He also receives support from the pro-Kurdish HDP. But his policy of social reconciliation across identity boundaries has failed for the time being. Kilicdaroglu reacted to this realization with an about-face in the election campaign. Instead of being more conciliatory, he now strikes harsh tones, especially against refugees. A small right-wing national party is now supporting him in the second round – which could frustrate Kurdish voters.

Ultimately, identity politics is more important for both sides – opposition and government – than anything else, says expert Aksoy. The country is deeply polarized. Erdogan, in turn, managed to forge a coherent Islamist-nationalist alliance. In uncertain times, people would have chosen a leader who they trusted to get something going politically.

“The Other Candidate”

Erdogan also used the media he dominated to portray the opposition as supporting terrorists. Erdogan even showed a manipulated video. International election observers also complain that the opposition is hardly ever featured in the media, and if it is, it is portrayed negatively. Pro-government broadcaster A Haber didn’t even bother to mention Kilicdaroglu’s name, instead calling him “the other candidate” in a recent graphic.

In an attempt to pierce Erdogan’s media dominance, Kilicdaroglu appears on the Youtube show Babala TV, which is popular with young people, shortly before the election. The concept is simple: the guest can be asked all sorts of questions, but only from the opposing side. Many questions are asked about terrorism combined with the accusation that the opposition supports the banned Kurdish Workers’ Party PKK – the government propaganda is getting through.

Kilicdaroglu explains why cultural promoter Osman Kavala must be released, even though Erdogan calls him a terrorist. The European Court of Human Rights ordered that, he says. Kilicdaroglu often uses the word rule of law and holds up a copy of the constitution he had brought with him six times.

Cansu Yapici says that for her, Kilicdaroglu’s first campaign was a bit like the forgiving “spirit of Gezi” finding its way into politics – a merger across identity lines, like back then in Gezi Park. The trend towards nationalism in Turkey, on the other hand, scares her. Many of her friends have already gone abroad, she says. But she will continue the fight for her rights even if Erdogan wins the election, “probably in a darker environment.”