Playing is one of those things, the word sounds light as a feather, like effortlessness, but it depends on the context. Playing an instrument is about seriousness, perseverance, the desire for perfection, at least if you set certain standards for yourself. What Michael Barenboim certainly did from the start is no different with this name. After all, the Berlin violinist is the son of the great Barenboim, which is why it is not easy to arrange a date with him.

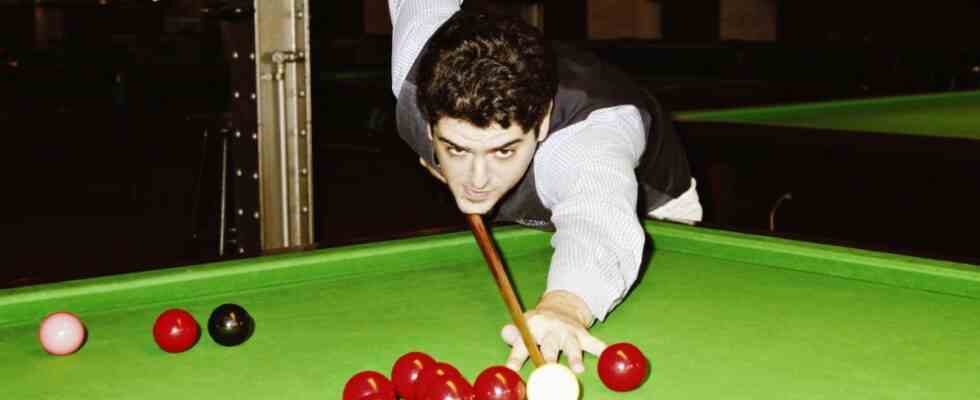

First the father’s health problems, then in January the news: Daniel Barenboim is resigning as General Music Director of the Berlin State Opera. That keeps the family on their toes. But finally the meeting succeeds, on a windy day in Schöneberg, in a bar with the vaudeville name “Billardaire”. Michael Barenboim also likes to play something lighter than the violin: snooker. It will quickly become apparent that he never quite gets rid of the instrumentalist.

Shirt, chinos, suede loafers and tweed waistcoat: Barenboim is always dressed appropriately, a timeless casual elegance that is often misunderstood as a geek look in Berlin. He simply finds vests comfortable to wear, says Barenboim – and snooker is a decent one waistcoat compulsory at tournaments, as well as shirt and bow tie. This comes from the history of the sport, which originated in British officers’ messes around 1870, as entertainment in clubs far from home in British India.

“I like that the sport doesn’t just explode.”

Even with cigars and the evening program, the attitude was maintained, hence the formality, which the 38-year-old likes in principle. “I like that the sport doesn’t just start shooting. You think about it first,” he says and pushes a green ball in a suitably restrained manner. Sunk. He acknowledges it with a nod, takes the chalk with which the tip of the cue is constantly whitened during a game – you could almost say manic with some professionals – for better friction, and wanders to the other end of the mighty table. Exactly twelve feet away. “Huge thing. I wouldn’t have room for that at home,” he says. In order to keep up the conversation, you keep following for the next 45 minutes.

Snooker is considered a difficult variant, where success depends more than in classic billiards on maximum concentration, tactical understanding, the calculation of angles. To snooker somebody means as much as “impeding someone, imprisoning” – often the balls arranged in a complex way cannot be played directly, it requires well thought-out sequences of several shots.

Barenboim, who regularly appears as a violinist with large orchestras such as the Vienna Philharmonic or the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, is now entirely a solo player. Fixes the arrangement of red balls and a few balls of a different color on the grass-green felt, briefly explains the tricky nature of the situation in question, tending to dampen expectations even before the shot with sentences like “It’s probably not going to work out now”. He would like to hit more safely and practice more often, he says and laughs. But the job as a busy soloist, always on the go, and as director of the Berlin Music Academy Barenboim-Said-Akademie leaves him little time. And he is a family man.

Clear strategy: Tactics play a particularly important role in snooker billiards.

(Photo: Christoph Voy)

In his mid-twenties, he started playing billiards with a friend. On concert tours it happens that he spontaneously walks into a salon in a foreign city, borrows a cue and plays and trains a little by himself. Always the same, familiar setting, the fabric-covered tables, the rows of lamps above, the atmosphere a mixture of nonchalance and concentration. The right images from films like “The Hustler” and “The Color of Money” are immediately in your mind, taciturn loners who, after much pondering, use the cue for the devastating blow.

In Berlin’s “Billardaire” there is not much going on this afternoon, but there are still one or two spectators, and Michael Barenboim seems to have more fun sharing the joy of success than shrouding himself in mysterious silence. “So, isn’t it?” he says when a shot (despite a negative prophecy) makes him happy and the balls roll over the felt with a loud click. “That’s how it should be, isn’t it?”

And the similarities to playing the violin? He straightens up and straightens his back. “First thing in common: the bent posture. Not very healthy.” But as a professional musician, he learned to take good care of his body and his intervertebral discs. Another parallel: no matter how hard you try for discipline and optimal training, the last little bit, whether a piece of music or a snooker set, a “frame”, succeeds perfectly, is not in your hands. “Was that control or coincidence? Or both? I find that fascinating. That’s why I love this game.”

The series of victories of the snooker superstars? He thinks it’s way too smooth

And then of course there is perseverance. A passage in a Mozart sonata that always fails, or a black bullet missed umpteen times in a standard constellation: “Try again and again and again,” he says. “As stupid as it is, you can’t back down.” At least not with the violin bow. With the cue he allows himself a bit more leeway. And leaves the real championship to the professionals, as spectators cheering in front of the screen, for example at the renowned Masters, which just took place in London.

Straight victories, which superstars like the Brit Ronnie O’Sullivan like to achieve in series, do not excite him as much as nail-biter games. “Failure or almost failure, those are the stories we all want to see,” says Barenboim. “After all, it’s about people, not robots.” Which in turn is a sentence that also fits well when a concert performance doesn’t go as well as he would like. You have to work hard to tick off an evening like this. “It’s easy to keep telling yourself afterwards how bad it was. Anyone can do that pretty well. The trick is to break free of it.”

Back to the snooker table, a few more jabs. Once a shake of the head (“Yellow is not possible today”), once a satisfied smile. Then the time is up, at the exit he fishes a handful of sour wine gums out of the glass on the counter. “Sweets!” calls Barenboim and puts a few in his mouth as he leaves. Outside on Monumentenstraße, everyday life is returning: first to the academy, then he has to stop by the day care center, a bag with a slightly dented children’s lunch box is dangling from the bicycle handlebars. A normal, tightly organized weekday. A game of snooker, on the other hand, has something of a little vacation to it.

No passion without accessories. Michael Barenboim needs these items to play snooker:

The balls

Order: In snooker, each of the six colored balls has its place on the table.

(Photo: Christoph Voy)

“In snooker, the colored balls have their place on the table and you try to pot them from those spots. So in training you’re repeating certain set pieces, which can be quite frustrating when things keep going wrong. It can happen , that at some point you can no longer see a color on a day like this.”

the cue

Support: The cue is placed on the so-called bridge.

(Photo: Christoph Voy)

“I have my own cue, which I bought when I was planning to play it more often. Unfortunately, I rarely get around to it and usually borrow one from the salon. I like the cues, they are elegant and feel comfortable in the hand . You can put them down on the so-called bridge. It looks pretty absurd when you play with an extremely long cue. At least I think so, and I hardly manage to keep it steady.”

The chalk

Ritual: Chalking the snooker cue.

(Photo: Christoph Voy)

“The chalk is to billiards what the bow resin is to the violin: They provide friction so that the sound unfolds or so that you can give the ball a direction. With some professionals you can see that the chalking of the cue is almost It’s a tic. Like tennis players who tap the ball umpteen times before serving.”

Swimming with Ulrike Folkerts, Collecting odds and ends with Johann Lafer, pet the motorcycle with Matthew Reim: More episodes of “My passion” do you think …? Find here.