John Akii-Bua later said his heart “pounded like a machine gun” in the hours leading up to the final. Akii-Bua, the son of Ugandan shepherds, ran the best time of all participants in the semifinals over 400 meters hurdles. And that despite the fact that he pulled his knees up a few times shortly before the finish line, as if he wanted to get rid of excess energy quickly. Nevertheless, hardly any expert trades it for the gold medal. Some say he lacks the necessary seriousness. Hasn’t he been spotted constantly at the Olympic Village disco? For others, the racist prejudice may have persisted that the hurdle discipline is too demanding for runners from Africa, too scientific.

Most hurdlers can only jump with one leg, left or right. You have to count the steps between the hurdles exactly, otherwise you won’t hit the jump cleanly. But Akii-Bua, the 22-year-old police recruit, has a special gift. Whether left or right: if the hurdle is there, he flies over it.

Track and field athletes call the 400 meter hurdles “mankillers” and every single run is an ordeal. Akii-Bua’s trainer, the Brit Malcolm Arnold, raised the hurdles by ten centimeters in training before the Olympics and put a twelve-kilo lead vest on his protégé. Arnold knows Akii-Bua can win. He just mustn’t think too much about what that win would mean beforehand.

The promises of independence are not being fulfilled in Uganda

In Munich, the young nations of the Third World claim their place on the global sporting stage. In Berlin in 1936 just 49 nations took part, in 1972 there were 121. The European colonies in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean have disintegrated. Ethiopian Abebe Bikila became an icon when he won the marathon barefoot in Rome at night in 1960, the first gold medal for an athlete from sub-Saharan Africa. Bikila’s triumph is an inspiration for the entire continent. Uganda freed itself from British rule in 1962, and the country has so far been denied Olympic gold.

The promises of freedom have not been fulfilled politically in Uganda, and corruption and tribal conflicts are hampering a new start. In 1971, the officer Idi Amin seized power, and many people initially pinned their hopes on the supposedly strong man. Among the brutal despots of Africa, Amin turns out to be the most evil, a pop star among the butchers who feeds his opponents to crocodiles. John Akii-Bua is a Christian and belongs to the Langi tribe – you can easily get killed for both in Amin’s Uganda. The dictator has banned radio and television broadcasting of the Munich 400-meter hurdles final.

“The whole stadium stood still in respect for a small nation on its way to disaster”

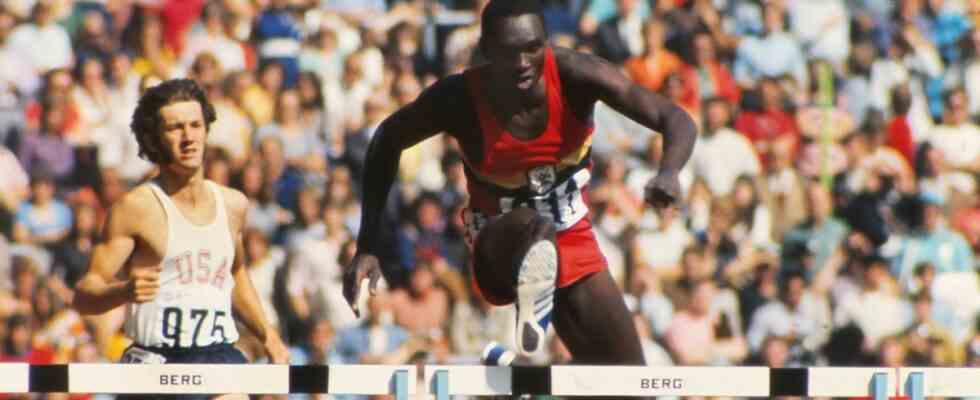

Akii-Bua doesn’t have to think about any of that as he dances around his starting block on September 2nd. The elegant Briton David Hemery is the favorite, especially since Akii-Bua was drawn to the inside lane, where cornering in the tightest radius requires even more power. Hemery goes strong, but at the beginning of the stretch Akii-Bua is tied. Apparently effortlessly he passes and runs to the historic gold. 47.82 seconds, world record, as the first person under 48 seconds. After crossing the finish line, he just keeps running with happiness, crossing invisible hurdles. In retrospect, the moment is regarded as the invention of the lap of honour. The Munich spectators could not cheer more enthusiastically if a German had won. This is extraordinary at a time when black athletes are still unabashedly called “black danger” by German journalists.

At the award ceremony, Akii-Bua wears a headband in the colors of Uganda, black, yellow and red.

Groundbreaking: John Akii-Bua not only invents the lap of honor in Munich, he also popularizes kissing the medal at the awards ceremony.

(Photo: AP)

“The Ugandan national anthem was played,” he later recalled, “and the whole stadium stood still in respect for a small nation on its way to disaster.” Uganda staggers with joy, Akii-Bua’s picture, like that of a saint, finds its way into the country’s houses and huts. Akii-Bua is aware that the dictator in Kampala cannot like this. After the closing ceremony, he said goodbye to his coach Malcolm Arnold in the dark in front of the stadium after four years together. One flies home to London. And the other returns in Idi Amins Uganda.

John Akii-Bua is now a folk hero, Amin can’t just murder him like hundreds of thousands of others. The despot is forced to receive him royally, and when Amin is again accused of systematically persecuting the Langi people from abroad, he points to the golden boy and says: “You claim I’m killing the Langi? Here they are.” Akii-Bua lives, but he lives in constant fear. He is not allowed to travel, three of his brothers disappear into Amin’s prisons.

In Idi Amin’s Uganda, Akii-Bua fears for his life every day – he takes refuge in alcohol

He missed Montreal 1976 because Uganda, along with 15 other African countries, boycotted the games after New Zealand’s rugby team lost an international match in apartheid South Africa. It is his “duty” to protest against “human rights violations,” says Amin. Akii-Bua has already moved into his room in the Olympic Village, for nothing. At home he takes refuge in alcohol and fears for his life every day. If he hadn’t won gold in Munich, he writes in his diary, “I could have escaped from Uganda. But I achieved the highest honor for my country, I couldn’t leave it. Uganda was like a prison.”

When Amin’s reign of terror came to an end in the chaos of war in 1979, Akii-Bua had his heavily pregnant wife and children smuggled to safe Kenya. The touching documentary film “The John Akii Bua Story” by Briton Daniel Gordon from 2008 tells how he manages to get out of the country himself: He is overtaken in his car by several Mercedes limousines with black, red and gold flags and hangs on the bumper – in the column of the German ambassador he crosses the Kenyan border. The Federal Republic is a kind of land of destiny for John Akii-Bua.

The homesickness grows and grows, he is no longer really happy

After a few months, a European camera team is filming in the refugee camp where he and his family are staying. A reporter accidentally realizes that the emaciated man crouching in front of him is the hero of Munich. The images also make it to Herzogenaurach, home of Puma, whose shoes Akii-Bua wore to his Olympic victory. Company boss Armin Dassler immediately decides to bring him and his family to Germany. He gets a job as a brand ambassador, there are wonderful pictures from those years: Akii-Bua cycles through Herzogenaurach, past half-timbered houses, people wave.

But the homesickness grows and grows. “It’s all here,” he says table football, “but your heart is far away.” His German companions such as Olympic javelin champion Klaus Wolfermann suspect that sooner rather than later Akii-Bua will return to his still shattered homeland. In 1983 the time had come. In Uganda, he first works as an athletics trainer and then as a police officer again. He won’t be really happy anymore. On June 20, 1997, he died impoverished in Kampala, according to official information of cancer. At Puma in Herzogenaurach, they still believe that AIDS was the real cause of death. One of the two red shoes in which John Akii-Bua ran to Uganda’s first Olympic gold medal in 1972 is in the archive there.