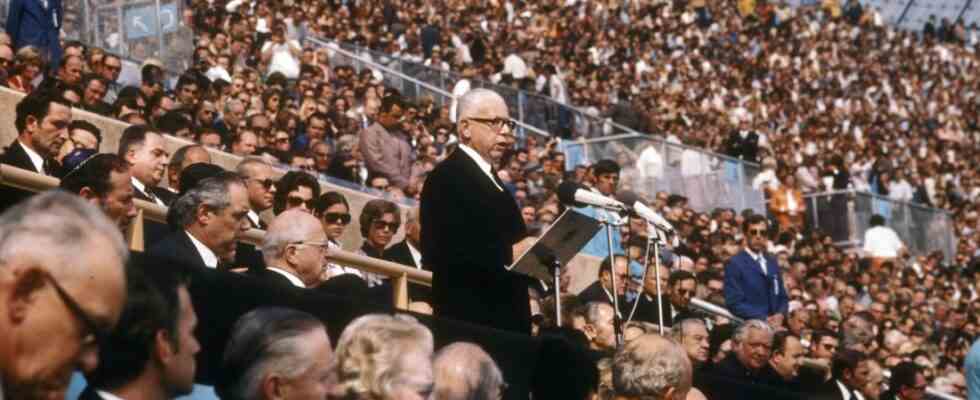

When it came to removing an excessive amount of pathos from a moment, then Gustav Heinemann was exactly the right man. At 4:15 p.m. on August 26, the Federal President rose from his seat in the VIP box at the Munich Olympic Stadium. He adjusted the double microphone briefly, then he spoke the opening formula, very seriously, but not at all moved: “I declare the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich to celebrate the 20th modern Olympics for him…”, pause for a second, right hand above, “…opens.”

Of course it was only a small sentence, Hans-Jochen Vogel, a social democrat like Heinemann, later said, but “a sentence that was heard all over the world”. Heinemann wanted to “symbolically set himself apart” from the opening ceremony in Berlin in 1936: “He didn’t let himself be celebrated in the stadium like Hitler and didn’t put himself in the center.”

Of course, the “cheerful games” that the organizers dreamed of reflected the social awakening of the Brandt era. But even more than the Chancellor, Gustav Heinemann became the political face of the Munich Games. If the sunglasses wearer Brandt embodied the new, then the horn-rimmed glasses fan Heinemann was a bridge from the old to the new for many Germans. Those for whom the Chancellor spread too much dynamism found the level-headedness and maximum seriousness of the Federal President, who was 14 years his senior, reassuring.

“Munich! Wonderful city!” Heinemann wrote in his diary as early as 1920

Heinemann, born in Essen in 1899 as the son of a high-class citizen, had spent almost the summer of his life in Munich as a young man. As a student in 1920, he roamed the Pinakothek galleries, saw Shakespeare in the theater and, shortly before his death, attended lectures by Max Weber at the university. “Munich! Wonderful city!” he wrote in his diary; the importance of the exclamation mark at Heinemann cannot be overestimated.

On May 19, 1920, he attended a rally of the NSDAP in the Hofbräuhaus, the speaker was the 31-year-old Adolf Hitler, who had returned from the war. “A sad picture of the state of mind and political illiteracy of our people,” noted Heinemann. As far as we know, he was thrown out of the room because of his heckling. According to his biographer Thomas Flemming, Heinemann may have been reserved, but he was also a man of “quiet passion” when it came to German democracy. He therefore had particular sympathy for the organizers’ plans to present the new, purified Germany to the world at the 1972 Olympics.

During the Nazi era, the evangelical Christian Heinemann had the “Green Leaves”, a church newspaper critical of the regime, reproduced in his basement. He resigned as Adenauer’s Minister of the Interior on principle, considering rearmament to be wrong; he left the CDU and joined the SPD. In the grand coalition he became Minister of Justice and dusted off German law: blasphemy, adultery and homosexual relationships were no longer criminal offences.

His election as Federal President is already “a step change in power,” he says

In March 1969, Heinemann was then elected Federal President with the votes of the SPD and FDP. It was “a bit of a change of power,” as he himself found it, anticipating Brandt’s election victory in the fall. And Heinemann anticipated something else, at least a little, a key principle of West German history. “Not less, but more democracy,” he said in his inaugural speech. “That’s the big demand, the big goal to which we all, especially young people, have to commit ourselves.”

Heinemann saw himself as a “citizen president” and wanted to be close to ordinary people. He even demonstrated his down-to-earth attitude when he invited to the Olympic reception at the beginning of the games in the Munich Residence. Where the following day at the gala hosted by Bavarian Prime Minister Alfons Goppel, a long evening dress, tuxedo or uniform was required, Heinemann expressly contented himself with a suit, short dress or traditional costume. Instead of lobster and veal fillet at a banquet table, his guests – including Prince Rainier and Gracia Patricia von Monaco – received hearty Bavarian fare. He personally had one name removed from the invitation list: Leni Riefenstahl, Hitler’s director of the 1936 Olympics, now accredited as a photographer.

Close to the normal people: Federal President Gustav Heinemann (second from right) is very interested in sports in the Olympic swimming pool.

(Photo: Imago)

In Munich, Heinemann much preferred contact with helpers and athletes than with crowned heads (“I have to say, the girls on the double bar – like spiders”). The only thing that annoyed him was that he was always accompanied by a large crowd of photographers on his numerous excursions to the Olympic Village: “I’ll soon go crazy if this continues.” He was particularly interested in international encounters. “Foreigners, have a go,” he called out in the Olympic youth camp. “Are there any ladies and gentlemen from an Eastern Bloc country in this room?” However, to be on the safe side, the ladies and gentlemen preferred not to say anything, just like the GDR athletes, to whom the Federal President asked whether the food tasted good. East Germans just pretended not to hear Heinemann.

On September 6, the Federal President spoke to the whole world again, an opportunity he would have gladly waived. It was the morning after the Olympic attack. Eleven Jews had been murdered on German soil, and Heinemann had the sole responsibility of representing the Federal Republic in its darkest hour. “We are stunned by a truly heinous crime,” he said. “In deep sadness we bow to the victims of the attack.” It was a dignified, credible speech, for which 400 citizens later thanked him in letters. The Israeli government was also satisfied because it made the Arab states, at least indirectly, responsible for preventing terrorism.

When Gustav Heinemann left office two years after Olympia, he renounced a large tattoo, torches and standing soldiers. He preferred to celebrate casually on a Rhine steamer.