analysis

Status: 05/16/2022 8:37 p.m

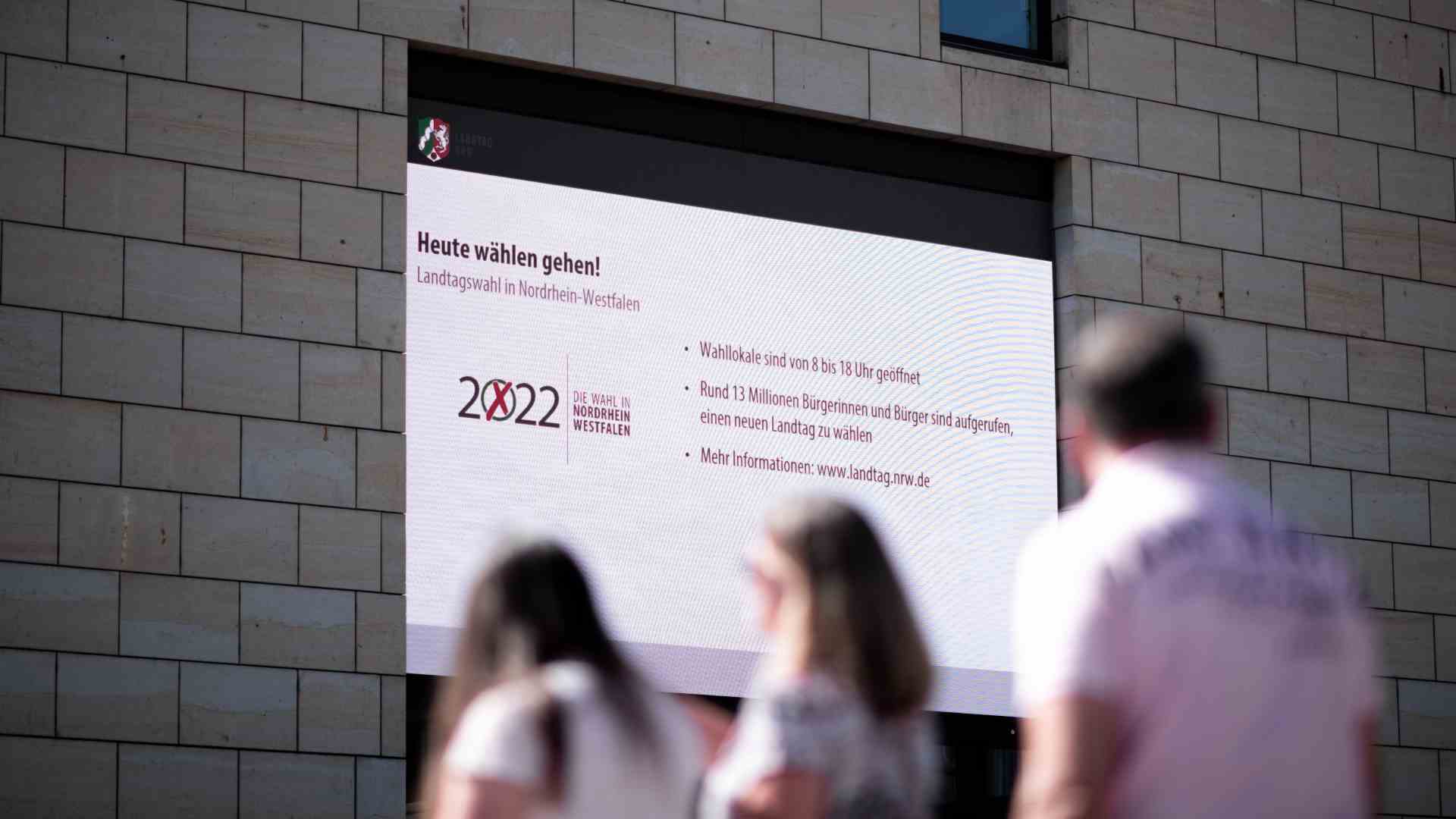

Only 55.5 percent of those eligible to vote in North Rhine-Westphalia cast their votes on Sunday. In 2017, participation was almost ten percentage points higher. Why is that?

With temperatures around 27 degrees last Sunday, many people in North Rhine-Westphalia let the sun shine on their stomachs. On the other hand, fewer citizens found their way into the voting booth than ever before in the history of the federal state. So beer garden instead of voting? It’s not that easy, says Julia Schwanholz from the University of Duisburg-Essen. The political scientist considers the weather factor to be “overinterpreted”.

Candidates hardly distinguishable?

It is much more important, for example, that the two top candidates and their parties were not easily distinguishable in the perception of many voters. According to Schwanholz, a head-to-head race, as indicated in the polls before the election between Hendrik Wüst (CDU) and Thomas Kutschaty (SPD), contributes to a higher turnout. However, there was – for example in the TV duel – little substantive demarcation between the top candidates, says the political scientist, who is an active SPD member herself. Therefore, for many eligible voters, it did not matter who wins the election.

So far, many non-voters have voted for the SPD

First analyzes of the election show that former SPD voters in particular did not vote this time. Compared to the last state election, the Social Democrats lost 390,000 votes to the non-voter camp – more than any other party. “We weren’t good enough at mobilization,” admits SPD general secretary Kevin Kühnert. Measured by the respective share of the vote, the AfD and the FDP also lost many voters to the non-voter camp. There were 180,000 former voters for the AfD and 140,000 for the FDP.

Mobilization and counter-mobilization by AfD 2017

More former voters migrated from the AfD to the group of non-voters than to all other parties combined. In the state election five years ago, the AfD still reached many protest voters, according to political scientist Schwanholz. They have now turned their backs on the party. Only the hard core of the AfD supporters remained.

A look at the AfD offers a possible explanation for why turnout has fallen by almost ten percentage points compared to the last state election. In 2017, the AfD “mobilized and counter-mobilized,” says Robert Vehrkamp, a democracy researcher at the Bertelsmann Foundation. At that time, the AfD managed to get many non-voters to the ballot box. At the same time, the prospect of a strong performance by the party mobilized many other people who wanted to prevent the AfD from being successful and only went to the polls for that reason. According to Vehrkamp, this mobilization effect by the AfD only briefly interrupted the general trend towards falling voter turnout.

Voter turnout of only 38 percent

The strong regional differences in voter turnout are striking. While significantly more than 65 percent of those entitled to vote cast their vote in Münster, it was just 38.1 percent in the Duisburg III constituency. One reason for this is the “extremely high proportion of people with a migration background” in the constituency, according to Duisburg political scientist Schwanholz. Some of them were overwhelmed by the election, not least in terms of language. Election programs and election notifications are only partially translated, Schwanholz complains.

Education as the key to more voter turnout

When it comes to the question of whether people go to the polls or not, the level of education is considered a key influencing factor. “Socially precarious milieus hardly ever vote anymore,” says Bertelsmann researcher Vehrkamp, ”representative democracy is becoming less and less representative.” For the parties, this entails the temptation to do more politics for their own electoral milieus, such as older people in the case of the CDU or academically educated city dwellers in the case of the Greens.

From Vehrkamp’s point of view, lowering the voting age to 16 can contribute to better political education. In this way, the schools could accompany the first election of young people and thus contribute to a higher turnout – with possibly lasting effects: “Anyone who votes in their first election usually also votes later in life,” says Vehrkamp. This could break the spiral of non-voting, especially for young people from non-voting families.