In Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland it is women who are in charge. At least, that’s how it seems, considering figures like Mary Lou McDonald and Michelle O’Neill, Sinn Féin’s two leading politicians – and the party’s soaring in the last election. The situation is similar in literature. Politically speaking, Sally Rooney is less interesting. Rather, it’s authors like Emilie Pine and Anna Burns.

One was born in Dublin in 1977 and the other in Belfast in 1962. In 2018, Burns became the first female author from Northern Ireland to win the Booker Prize, the UK’s top literary award. The younger Pine topped the bestseller list in Ireland with her volume of scandalous essays, Notes To Self.

In these texts, Pine writes about the fact that in her country there is still no appropriate language for the body, especially that of women. She asks what it means for society if essential aspects of the existence of entire groups are not named. She plays through this question using the example of various topics in her own life. She writes about the children of drinkers, how little room there is for grief after a miscarriage, or what the 1997 Irish referendum meant for a liberal divorce law that directly affected her mother.

In Cornelia Röser’s translation, too, the essays sound drastically direct and at the same time offer the generalized analysis: her book also deals with the health system and its inhumane language, with the lack of care for young people. And again and again Pine writes about powerlessness, speechlessness, shame. Against the silence about feelings, she uses the refrain: “That’s how it feels.”

Bulimia is also one of Pine’s themes, and that, like much else, ties her to the characters of Anna Burns, Burns being the more aesthetically impressive author of the two as well. Anna-Nina Kroll translated the excellent novel “Milkman” from 2018 into German so fantastically that one’s ears are still flapping at the linguistic madness with which Burns translates the deformation of society into style. Remember the first sentence: “The day Somebody McSomething put a gun on my chest, called me a whore and threatened to shoot me was also the day the milkman died.”

Now there is also Anna Burns’ debut in German, the novel “Amelia” from 2001, again translated by Anna-Nina Kroll. You can still see the practice mode. But at what a level! It almost looks like Pine’s “Notes To Self”: a collection of individual texts that belong together but were created individually.

Even the children are jaded and senile from the ongoing civil war

Sometimes the story is told from Amelia Lovett’s first-person perspective, sometimes from that of another character or that of an external authority. It doesn’t look like a multi-perspective program, but more like etudes, born out of an angry survival energy and pure fun with the linguistic possibilities. As later in “Milkman”, the focus is on the experience of a girl. Amelia is nine years old when we meet her and her friends, most of whom will be dead by the end of the book.

The few survivors try to go on an excursion – an unimaginable, fearful undertaking for young people with their experiences. Burns tells of the glimmering spark of longing for another life, which makes it all the more clear how dead these young people are, prematurely aging, of war and civil war and the brutalization of adults: “They were watching something on television about a possible armistice when Amelia made an outrageous suggestion out of the blue. It was so outrageous that everyone looked at her. ‘What do you mean?’ they roared. ‘A trip? But why? What’s wrong with being here?'”

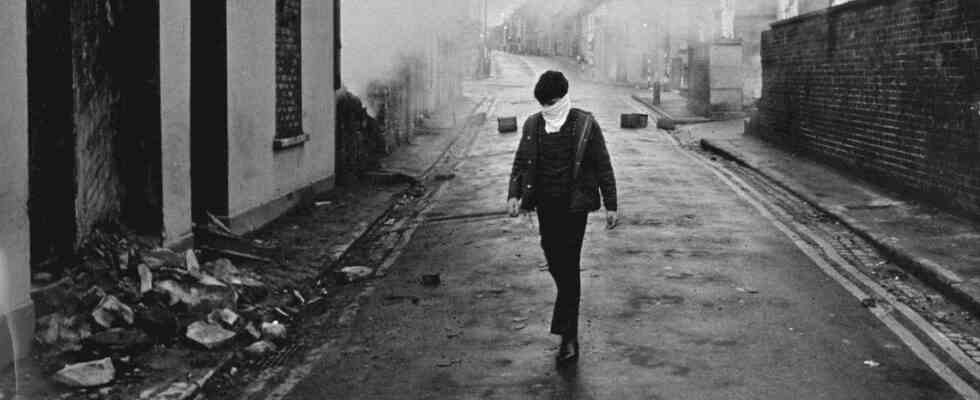

Amelia’s story ends in 1994, four years before the Good Friday Agreement. The story begins in 1969, shortly before the so-called Troubles, before the IRA split into Provisionals and Officials, before the escalation of violence on all sides, denunciations, vile murders and brutal excesses.

And where are the adults? On the street, chasing people

The novel is set in the working-class Catholic neighborhood of Ardoyne in Belfast, where Anna Burns grew up. Her childlike perception of her characters allows her to delve deeper into the pathologies of Northern Irish society than any account of political violence would. For example, there is the girl Bossy, who wants to make herself important to her friends and excitedly tells them that she has heard about riots. Bossy meets with disinterest: “How could something be so dangerous that they couldn’t carry on as usual?”

This is where violence announces itself, but Anna Burns switches to the inner life of Bossy, who has been punished with ignorance by the others: “She thought they needed her.” It is also destructive when there is no kindness, when one sadistically exploits the neediness of others. Things are already out of whack in Ardoyne before the Troubles.

Burns follows the narratives of social hardship known from authors like Frank McCourt, but takes it a step further. Like Emilie Pine, she attacks the institutions, the school, the church, that make children and adults feel “unable to function”. She shows the paradoxical strategies of self-protection that the children develop.

The children don’t want to write poems for peace

Brilliantly over-the-top scene where Miss Hanratty, a teacher who regularly “rakes her thighs” in a skipped act, gets it in her drunk brain that the kids should write poetry for peace. But they are interested in other things: “Roberta wanted to write about stairs and stairwells because she loves stairs. ‘I went up the stairs, Amelia’, Roberta went into detail. They hung up their jackets in the cloakroom and took off their rubber boots ‘Then I went down the stairs. Then I went up the stairs again. Later I went down the stairs again…'”

Potato printing fascinates Bernie, and Amelia likes cruel poetry but not prescribed peace formulas. The children retreat into the fringes of their ordered rhymes, and it just gets crazier, ever so slightly: “Amelia swung and swung her legs under the table, putting the finishing touches on it and seriously contemplating writing another poem about peace, when a Miss-Glocki-Adretti-Klamotti came and snatched it from her.”

Two years later, in 1973, it sounds like this: “The dropping of a pin and even more the cracking of a sibling’s bone or the banging in of a relative’s skull were enough to saturate the area with troops and the up-and-coming Irish organization large, but also really, really great inconvenience.”

Despite all the misery, the story is always really funny

Laconicism and absurdity shrug it off when a father crushes his son with a gas stove when the brother pasolini-like wants to abuse the underage bulimic sister for sado maso games, but then gets ripped to pieces by another sister with her slavering followers in an excellent Penthesilea scene.

And where are the adults? On the street, chasing people, fighting, making children pregnant. But in the houses there is silence. There are also the vulnerable, who direct all this distress inwards and not outwards. Anna Burns also describes their madness in scenes that can be read as early reflections on her own dealings with British-Irish relations.

As an English therapist says to his young Irish patient: “Jat and Mickey are imaginary characters and you embellish them in great detail, but they remain imaginary, Vincent. Without you they wouldn’t exist.” A special quality of the author consists in always being really funny despite all the misery. Like when a guy Amelia gets in the car with in 1983 can’t decide which of his attitudes to give more weight, racist or misogynistic. As a British Army telescopic sight pushes out of the bushes, the poor wretch calls out, “‘Black man!’, ‘No, white woman!’, ‘No! Wait! Black man’, ‘No! No! Wait a minute! White people Woman!'”.

In Burns, the line between good and evil does not run between the sexes

Burns rounds off the rhetorical punches with a nasty change of register: “Because Janto couldn’t stand ambiguity, ambivalence, abstraction, paradoxes, and any confused in-between, he ended up choosing to be black and make ends meet rather than a woman to be no matter how white.”

Incidentally, one can see from Kroll’s translation how one can write such a passage without repeating racist terms. What possibly connects Anna Burns and Emilie Pine with politicians like Mary Lou MacDonald and Michelle O’Neill is the insight that political violence, but also patriarchal and conservative institutionalized violence, must come to an end. Pine and Burns describe their consequences for individuals and society.

In Burns, the line between good and evil does not run between the sexes, but between the stubborn realists and those who never stop turning to others. Incidentally, the psychoanalytic reflection is still noticeable in Burns’ debut and Emilie Pine’s essays. In “Milkman” it was completely absorbed by the aesthetics.