The Boulez Hall in Berlin, built by Frank Gehry, wants to establish “music for the thinking ear” as a “vision”. But a thinking ear must make all sorts of musical contacts: acoustic, philosophical, historical.

So had the Belgian Julien Liberer an unusual idea. He picked up the preludes and fugues of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, only those in the major keys of part one, and after each fugue inserted a piece written after Bach in the minor key of the same name – from Mozart to Brahms to Shostakovich. Nothing but colorful leaves in the assumption that Bach & Beyond would result in a “well-tempered conversation”. Sometimes an exciting one, since the “conversations” can even turn into confrontations or feuds. So when, after Bach’s C major pair, Beethoven’s little-known C minor bagatelle without an opus number is heard, in which Libeer appreciates the “obsessive rhythm”. In the booklet he explains his procedure in minute detail. Or when György Ligeti sounds after Bach’s A major, a petitesse from his Musica ricercata, which defiantly only drills on the A. Chopin’s Mazurka in C sharp minor or Ravel’s Fugue in E minor from the Tombeau de Couperin sound like obscure continuations of Bach’s. One listens with curiosity to miniatures by Mozart, Busoni and Reger, by Rachmaninoff or Fauré. Finally the coup: after the last Bach fugue in B minor, Libeer ends his playing with Schönberg’s lightning-fast, atonal Little Piano Pieces op.19. Such a Bach experiment succeeds for two reasons. First, Julien Libeer, pupil of Maria Joao Pires, plays Bach and the posthumous partners with smooth articulation, mature pianism. Secondly, various aspects unfold from the historical-aesthetic mixture that illustrate how great the Bach cosmos challenged and inspired later composers (harmonia mundi).

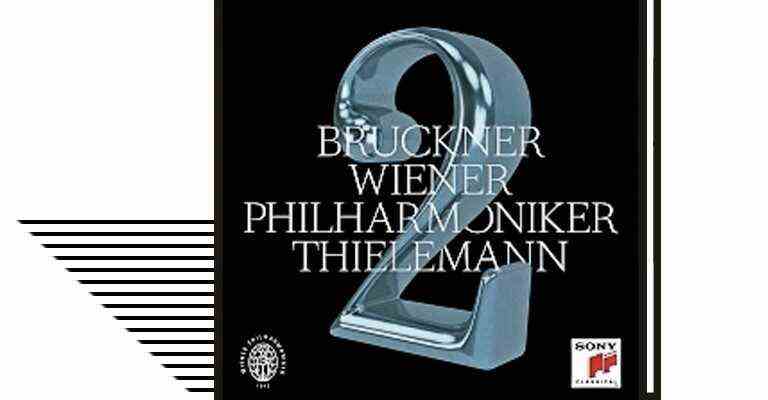

The Vienna Philharmonic likes to meet up with you Christian Thielemannwhich they a new Bruckner cycle owe, now topped up with the less frequently played Second Symphony in C minor. Even if the cliché of pompous sound and cathedral-like pious solemnity is constantly saddled with the master of St. Florian – his alone spiritual Concentration, yes strength remains the challenge for “thinking ears”. Bruckner’s genius of motivic combinatorics, which he embeds in the beauty of sound, comes close to Bach. Thielemann makes this audible with the four movements of the feverishly bubbling second. He forms the network of relationships of polyphonic connections in a stabilizing manner into large, nuanced sound arcs, without mystifying pathos. Thielemann has the breath to organically merge the symphonic dimensions of the background Bruckner music with its blossoming melodic finesse (Sony).

A calendar-based program idea as access to Wolfgang Amade Mozart and his huge cookbook? This can work if his music is sorted according to the year it was written, say 1785. This resulted in six recordings with which the pianist Leif Ove Andsnes Highlights from Mozart’s highly productive year are presented. These are three piano concertos, the heavyweights Köchel 466, 467 and 482, for which the pianist from Norway mobilizes precision and sensitivity together with the filigree Mahler Chamber Orchestra, which he directs from the grand piano. The pianist succeeds in the dark drama of the C minor Fantasy K. 475 with a hint of depth. The Masonic Funeral Music is the oppressive encore, unlike the piano quartet in G minor, which boasts the finest brilliance. 1785 Mozart’s creative power triumphed (Sony)

The mystery figure Domenico ScarlattiNeapolitan baroque composer, emigrated to Spain and, as the queen’s private harpsichordist in Madrid, was only busy with his 555 one-movement piano sonatas, the musician has it Ulrich Eckhardt done. The trained pianist and lawyer, who has been director of the Berliner Festspiele for decades since 1973, has retained the desire, strength and enough restlessness to make music even in old age. After his Satie CD and the Michelangelo poems read by Jutta Lampe with piano music by Frederic Mompou, Eckhardt pounced on Scarlatti. He plays concert recordings in Berlin-Dahlem, the Scarlatti treasures as “profane art music”, he writes, “which never allows itself to be condescended for representational purposes”. As a lover who is fond of the piano without the customary virtuosity pressure, and all the more fond of the composer Scarlatti, who navigates freely between calculation, pathos and irony, his interpreter provides studies of “early” music (note & sound) that thinks forward as modernity.