No sooner had the Olympic Stadium quietly emptied that morning, no sooner had the 80,000 participants left the funeral service for the eleven murdered Israelis in a depressed mood, than columns of helpers moved in and removed the chairs from the lawn on which the athletes were just sitting were seated. It should, it had to go on, “the games must go on”, said the IOC President Avery Brundage himself in his speech. And on the evening of September 6th, they actually went further, when the ball was already rolling over the lawn again at the soccer match between the Federal Republic of Germany and Hungary. Luckily the Germans lost 4-1, so at least there wasn’t a reason to cheer for the 75,000 spectators.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) did not hesitate long to mourn and commemorate the terrorist act of September 5, 1972. It moved on to the next host cities and left Munich to deal with it alone. The city then suppressed the terrible events as best it could and pushed the memory a little to one side. Three months after the event, on December 10, 1972, a commemorative plaque was unveiled next to the entrance to Connollystrasse 31 with the names of the Israelis killed in German and Hebrew script.

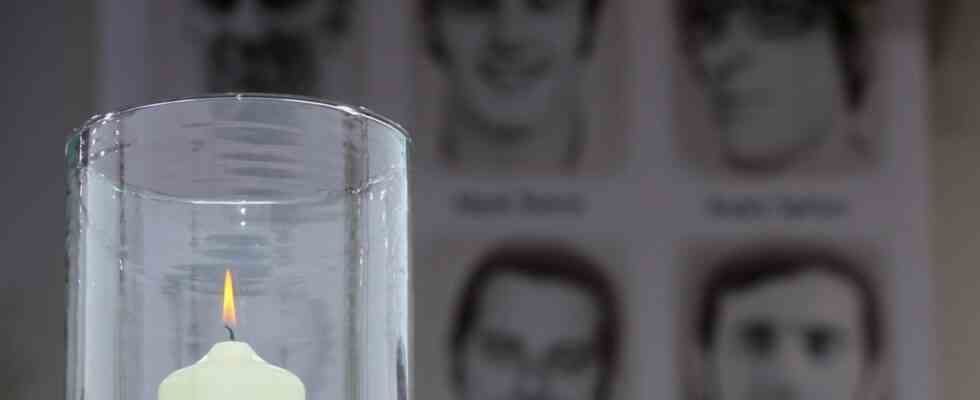

For a long time, this was the only place in Munich where there was evidence of the attack – unless you walked past it carelessly. And although Willi Daume, the head of organization at the Munich Games, announced during a memorial service on the first anniversary that he would talk “with important artists” about the construction of a memorial, possibly even in the Olympic Park.

The plaque at Connollystraße 31 in the Olympiadorf remained the only place of remembrance for a long time.

(Photo: Florian Peljak)

It was the representatives of Israel and the Jewish religious community who kept the memory alive, and the commemoration of September 5 was increasingly pushed into the background by the general public in Munich. On most anniversaries, only wreaths were laid, but local and state politicians attended the funeral services on the round ones. It took almost a quarter of a century before the culture of commemoration and remembrance was breathed into life. However, the impulse for this did not come from Munich, but from Fürstenfeldbruck, the place where most of the victims of the hostage-taking died, but which was basically not responsible for the fact that it had been chosen as the scene of a bloodbath.

On the initiative of a young district administrator, Fürstenfeldbruck establishes an annual event

In the district of Fürstenfeldbruck, a new district administrator was elected in 1996, Thomas Karmasin (CSU), at 33 the youngest in Bavaria. As a student, he experienced the terrible night in his hometown of Fürstenfeldbruck during the summer holidays. As a politician, he saw it as his duty to keep the memory of the victims alive and to give the commemoration a place. And he immediately got to work, even against various odds. In Fürstenfeldbruck, in the days, years and decades after the attack, only a few people paid attention to the victims – but on Karmasin’s initiative, a memorial was inaugurated in front of the main gate of the air base 27 years after the massacre and a memorial event has been organized every year since then. Charlotte Knobloch was there on September 5, 1999, as she was in all the years that followed.

The memorial in front of the air base in Fürstenfeldbruck was created in 1999.

(Photo: Johannes Simon)

The president of the Jewish religious community was 39 years old on September 5, 1972 and, as she once said, very worried about her daughter because she hadn’t heard from her. There were no mobile phones, so Knobloch spent anxious hours waiting for her daughter, who was employed as an Olympic hostess. She was then involved in the planning of the Fürstenfeldbruck memorial, which commemorates that September day, just like the former Mayor of Munich, Hans-Jochen Vogel, and District Administrator Thomas Karmasin.

Since 1999, at the invitation of the district office of Fürstenfeldbruck, people have come together every September 5th in front of the memorial created by the Gröbenzell artist Hannes L. Götz. The memorial in the shape of the Olympic flame has twelve stylized flame jets, each for a name of the twelve victims, eleven Israelis and a Bavarian policeman. It is a simple memorial stone, but due to its location directly on the barracks wall, it is hardly noticed by the public. The speeches by the District Administrator and Charlotte Knobloch as well as the decent, appropriate musical accompaniment have become a tradition. For several years, the respective representatives of the Israeli Consulate General in Munich have also taken the floor, and Catholic and Protestant clergy have said a prayer together with a rabbi.

The relatives of the Israeli victims were invited to the first really big commemoration event in 2002, but they didn’t come for a commemoration ceremony in their own country. To do this, they traveled to the 40th anniversary of the attack in 2012. Twenty years ago, like ten years ago, the question of an appropriate compensation payment was still unresolved and controversial. Because the demands were not met until recently, the Israeli survivors threatened not to attend the 50th anniversary commemoration. Only a short-term success in negotiations made the visit of the delegation with Israeli President Isaac Herzog possible in Fürstenfeldbruck on Monday.

The tower of the airfield is to be preserved as a place of remembrance

They would like to do more commemorative work there, but despite all the idealistic and political preparatory work, it’s also about money there. The district is hardly in a position to put more money into projects from its own resources. That is why, for example, the digital place of remembrance in the form of a website and an app pushed by Karmasin and the district council has only just been completed. Another goal of the city council and district council remains that the old tower becomes a real place of remembrance because of its authenticity.

Even if the building doesn’t look like it does in the iconic photos from 1972 from the outside, not much has changed inside, as eyewitnesses confirm during visits. Politicians at all levels, right up to members of the Bundestag, have been calling for the tower to be preserved and for public access for years. The historic building is federally owned and fenced; around it, the Bavarian police can complete their driver safety training course, and BMW has also established its driver training course. The main entrance still leads through the barracks. A visit to the tower is only permitted for registered events.

The complaining beam in the Olympic Park: the names of the eleven killed Israelis and the killed policeman are engraved on the memorial by the sculptor Fritz Koenig.

(Photo: Stephan Rumpf)

In Munich, too, one of the “significant artists” that Willi Daume had spoken of in 1973 had meanwhile created a sculpture as a memorial to the victims of the Olympic attack. The work by the sculptor Fritz Koenig, entitled “Wailing Beam”, had even been installed in the Olympic Park in September 1995, on the way from the village to the stadium. From an artistic point of view, the ten-meter-wide granite beam was also universally praised, but from a practical point of view, most visitors largely avoided it. Especially since it is not self-explanatory for unbiased tourists.

In fact, there has only been a really attractive and appealing memorial in Munich for five years, not far from the complaint beam, actually in the Olympic Park, as promised decades earlier by Willi Daume. This memorial was opened on the 45th anniversary of the attack in September 2017 in the presence of the victims’ relatives and the two Presidents Frank-Walter Steinmeier and Reuven Rivlin. The course of the attack is described and classified in a multi-media pavilion; In addition, one learns biographical information about the eleven Israeli Olympians and the Bavarian police officers who were killed by the Palestinian terrorists at the time.

“To stand on the hill today is a most moving historical event,” said Ilana Romano, widow of weightlifter Yossef Romano. After “years of refusal” by German politicians, the relatives are “grateful and full of pride”. Even Ankie Spitzer, who since the murder of her husband, the fencing coach Andrei Spitzer, has been fighting tirelessly to ensure that the act of September 5, 1972 is forgotten, praised the “beautiful, moving memorial”.

Cut: The multimedia memorial in the Olympic Park was opened in 2017 on the 45th anniversary.

(Photo: Stephan Rumpf)

In any case, it has a lot of symbolic power, more than all the others. It is within sight of the house at Connollystrasse 31, where the drama began. It is mounted on a hill, which can be understood as an incision – in the lives of the victims and their families, in the history of the city of Munich, in the history of the Olympic Games. You can also see them as if the victims had finally been brought out of the blue. And in view of the circumstances of the attack, which are still far from clear, the memorial allows for another conclusion. The policeman Werner Brandl, who was on duty in Fürstenfeldbruck 50 years ago, put it in such a way that “the whole story is still covered”.

And it is aired very slowly. The IOC only paused again in 2021 in Tokyo to commemorate the victims of the 1972 terrorist attack. There was a minute’s silence at the opening ceremony. But then the games went on again quickly.