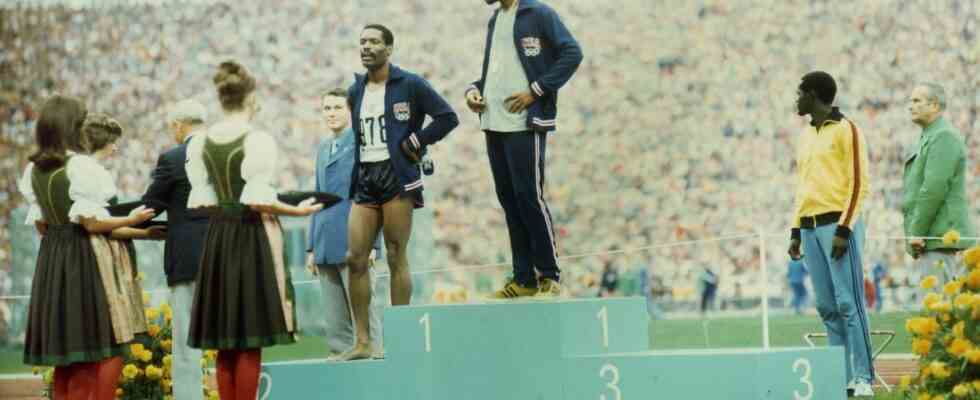

Men’s 400 meter award ceremony. Kenya’s Julius Sang stands upright on the podium, his bronze medal hanging over his track jacket. He looks quietly in the direction of the hoisted flags, listening intently to the national anthem “The Star-Spangled Banner”, which is played for the two Americans who placed first and second. But she doesn’t seem to be interested, they chat in the meantime.

Vincent Matthews, the gold medalist, looks around and tugs at his goatee with one hand; the other rests casually on the hips over the open training jacket. Wayne Collett, the runner-up, has joined the top step of the podium – barefoot and in shorts. Collett later explained his behavior as a protest against the treatment of black people in his country: “There is a lot wrong and I think the white establishment is just too careless about America’s black people. They don’t care about us – unless we embarrass them a little.”

A political protest, albeit not as spectacular as that of Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. At the time, the Americans raised their fists in the air and lowered their gaze at the 200-meter award ceremony – the pictures became a symbol of the Black Power movement worldwide. Matthews and Collett, on the other hand, appear less combative in Munich, more disillusioned. When leaving the stadium, Collett raises his fist in the air – and promptly gets whistles and boos from the audience.

Banned at the Olympics back then: American track and field athletes Tommie Smith (centre) and John Carlos (right) raise their fists in the air to protest racism at the 1968 Games in Mexico City.

(Photo: AP)

Contrary to the assessment of a spokesman for the US team that the September 7 action was “not a big deal that should have consequences”, Matthews and Collett were hit hard: The International Olympic Committee (IOC) banned them “for improper conduct at the award ceremony” for all further competitions in Munich and demanded an apology. Matthews and Collett declined – they were never allowed to compete in the Olympics again.

“As a comprehensive movement, the Olympic Games have always been used as a platform for political messages. The greatest possible attention is achieved through their popularity and media coverage,” says Stephan Wassong, Professor at the Institute for Sports History at the German Sport University Cologne (DSHS). The protest rallies are always embedded in the context of current political events.

“The early protests were not sanctioned by the IOC until 1960. In the 1960s, the international situation changed dramatically. The IOC may have seen the need, against the background of international tensions, to rigorously protect the Olympic Games from political propaganda.” , Wassong believes. Athletes like Smith and Carlos, Matthews and Collett drew attention to the precarious situation of the black population in the USA. Any “political, religious or racist demonstration or propaganda” is prohibited at the games. That’s what Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter says.

With Cathy Freeman, the IOC does not dare

However, this has not stopped athletes from using the games for their political messages. Australian boxer Damien Hooper, for example, stepped into the ring in London in 2012 wearing a t-shirt with the flag of the Aborigines, the indigenous people of the continent. “I represent my culture, not just my country,” said the boxer of indigenous ancestry. Hooper was cautioned by the IOC and formally apologized after being threatened with disqualification.

Cathy Freeman had a different experience twelve years earlier in Sydney. At that time she won over 400 meters and, in addition to the Australian flag, also grabbed the Aboriginal flag on the lap of honour. She is also descended from the natives, but she was their symbol at the time and the face of those games in general. A penalty was out of the question. “The sanctioning of protests is a case-by-case decision. There is a discussion and then the proportionality is weighed up,” says Wassong. In the case of the globally known Freeman, punishment would probably have given the IOC negative headlines.

The IOC justifies its protest ban with the fact that the Olympic Games are apolitical. Wassong, who also conducts research at the Center for Olympic Studies at the DSHS, sees it that way: “For a certain time, the Olympic Games offer the possibility that, despite political ice ages and wars, representatives of different nations can succeed in bringing together. And it does.” Benjamin Bendrich sees it differently, he conducts international research on athletes’ rights and says: “Rule 50 should be abolished.” He is not alone with this opinion. The protest ban contradicts Article 19 of the UN Declaration of Human Rights, the right to freedom of expression, the critics argue.

In the meantime, the athletes stop protesting – and increase their wealth

“In the 1980s and 1990s, the focus was on the commercialization of sport. Athletes were probably more interested in securing their wealth and there were fewer protests,” believes Bendrich. With the advent of social media, an increase in political demonstrations can be seen again. “It’s not just the quantity that has increased,” says Bendrich. “Black athletes are now receiving support from athletes who are not affected by the problems themselves. It’s new that all athletes show solidarity. That’s what makes the new movement so strong.”

It is crucial that the protests are compatible with basic human rights: “If no other people are insulted or injured, protests of any kind should be allowed – and in my opinion it is also useful to push social changes.” By spreading the protests via social media, the IOC has less control. “The IOC is aware that the public is more conscious of the problem and is no longer so easily fobbed off. That is why they are acting more cautiously and weighing things up,” says Bendrich. He says the IOC has moderated its stance.

In July 2021, ahead of the Tokyo Games, Rule 50 of the Charter was amended. After athletes had criticized the rule, political protests are at least possible to a limited extent. With the participation of former sprinter Carlos raising his fist in Mexico City, the athletes’ representation of the US Olympic and Paralympic Committees pushed for the protest ban to be lifted entirely. In consultation with the Athletes’ Commission of the IOC, a compromise was found that expressions of opinion remain prohibited at official ceremonies such as award ceremonies or opening and closing ceremonies, on the field and in the Olympic Village. However, athletes are allowed to express themselves politically at team meetings, press conferences and before the competitions.

“The rule was only slightly changed. For me, that’s window dressing,” said Bendrich. The independent association Athleten Deutschland also complains that the ban on protests is being retained in certain cases. Wassong, on the other hand, is behind the new regulation: “Highly polarizing and politicizing protest rallies carried out during competitions can distract athletes and thereby lead to a distortion of performance, which has been worked for years to achieve optimal execution.” The sports historian also fears that political statements, for example during the opening ceremony, would “make them a breeding ground for political conflicts”.

Now allowed at the Olympics: American soccer players will kneel at the 2021 games in Tokyo to demonstrate against racism.

(Photo: Masatoshi Okauchi/Shutterstock/Imago)

In Tokyo, the footballers have already made use of the rule change. The teams from Great Britain, Chile, Sweden and the USA took a knee before kick-off to protest against racism, the Australian players waved the Aboriginal flag, thanks to the relaxation of the rule. Nike Lorenz, the captain of the German hockey team, was allowed to wear her rainbow armband, but only after the German Olympic Sports Confederation and the German Hockey Federation submitted a joint application to the IOC.

American shot putter Raven Saunders crossed her arms over her head at the awards ceremony to express solidarity with oppressed people. A political gesture that is still prohibited on the podium under Rule 50. “Let them try and take that medal,” the silver medalist tweeted after the IOC began investigating. In the end, there was no penalty.

“By now everyone knows that sport and politics always mix. But the IOC only wants to be political when it fits into its own agenda,” says Bendrich. For example, in 2018 the IOC supported the joint women’s ice hockey team from North and South Korea. Even the awarding of the games in countries that are not known for their observance of human rights and only use the Olympics for advertising purposes does not indicate a separation of sport and politics.

The fact that a Uyghur athlete lit the Olympic flame at the 2022 Winter Games in Beijing while Uyghurs are being locked up in internment camps is not just something Bendrich sees as a staging: “These are all political actions. But if there are protests from athletes, the IOC refers to them again “To be apolitical. That’s problematic because it’s not possible to be both at the same time.”