Fifteen years is the average length of a journalistic career in France. More and more of them are abandoning the profession that makes them dream to escape the precariousness and the hellish pace in the digital age. In a book called Yesterday, journalists. They left the profession, the sociologist of the media, Jean-Marie Charon, researcher at CNRS and IHESS and Adénora Pigeolat, researcher at Havre Normandie University, try to analyze the phenomenon.

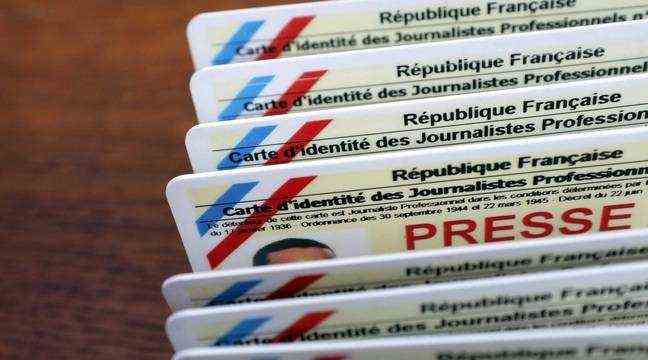

The figures speak for themselves: the number of journalists holding a press card was 34,132 in 2020, against 37,392 in 2009, the most prosperous year, i.e. a drop of 9.55%, according to the social barometer presented by Jean-Marie Charon on the occasion of the Journalism Assizes which are held in Tours until Friday.

A sharp drop due to the health crisis

The year 2020, due to the health crisis, which triggered several social plans, bankruptcy filings and hiring freezes, was marked by a sharp drop: 389 fewer press cards, the biggest drop since year 2015-2016.

To understand this phenomenon, Jean-Marie Charon and Adénora Pigeolat interviewed around fifty former journalists or journalists in the process of retraining, in all French regions, the Antilles and Réunion included.

Young people and women turn their backs on the profession

The fairly large proportion of young people (35 years or less) leaving the profession struck the duo of researchers. “These departures are all the more appealing as the profession has rather aged in recent decades (average 44.7 years)”, they note.

For the most part, it is women who turn their backs on the profession: “They represent two out of three people in the interviewed panel”. Among those who have left, many have experienced periods of insecurity (freelance work, fixed-term contracts, unemployment, unrecognized statuses, such as self-employment).

An increasingly precarious profession

According to figures from the joint committee responsible for issuing the press card, the CCIJP, the share of precarious journalists (freelancers, unemployed) continues to increase in the profession: 27.6% (more than one in four journalists) and affects women more (30%).

Many people say they are disillusioned: they dreamed of being the great reporters and found themselves a Web editor. Others emphasize the extended hours, with the weekends and evening on-call duty.

Many burnouts

With the advent of digital technology, since the mid-1990s, the written press has seen its revenues collapse. At the same time, working conditions have deteriorated significantly. “The Shiva journalists who make up our editorial staff can no longer take it”, according to one of the witnesses quoted in the book. In total, “85% believe that they are asked to work faster than before”, it is still written.

And activity is getting poorer: for many, the Web is reduced to a “copy and paste of dispatches”. In television, it can be boiled down to “filming press conferences”.

Many report burnout, a phenomenon that affects women more than men. Some report discrimination and sexism. “The highest hierarchical levels are occupied in majority, even exclusively, by men”, underline the authors, evoking the famous “glass ceiling”.

A professional life after the press

In any case, there is a professional life after journalism, especially in the fields of “teaching and communication”. Like some big names in the press who have joined in the past the services of the Prime Minister, or even the President of the Republic, the respondents have embarked on the institutional communication of municipalities, departments or regions. Others, already specialized in a field (culture, automobile, etc.) “end up accepting an offer from their old sources”.