More than 9,000 tons Machinery and machine parts orbit the Earth, including satellites, the International Space Station and debris. However, a large part of this metal mass is made up of the almost thousand inoperable rockets that have been left in space since the beginning of the space age. So far there is no way to remove them.

Advertisement

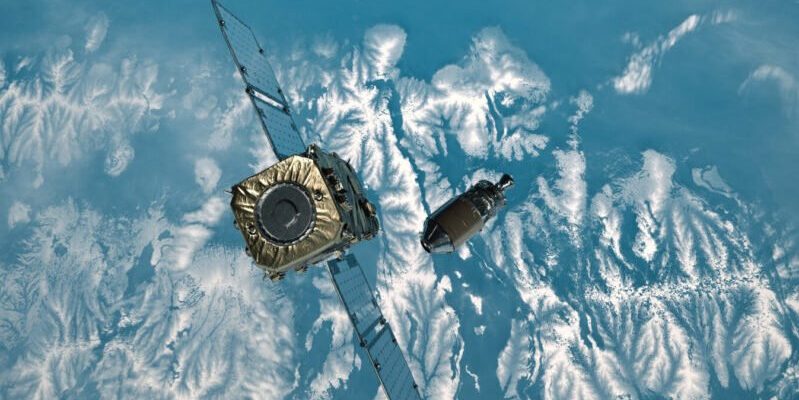

On February 18, the New Zealand company Rocket Lab launched a spacecraft which has since been on a rendezvous course with such a space debris rocket. The rocket is expected to reach it in the coming weeks. The spacecraft, called ADRAS-J (Active Debris Removal by Astroscale Japan), was developed by the Japanese company Astroscale and funded by the Japanese space agency JAXA. Once it arrives, it will examine the decommissioned rocket and figure out how a follow-up mission could bring it back into the atmosphere.

If the mission is successful, it could demonstrate how to remove large, dangerous and uncontrolled pieces of space debris from orbit – objects that could cause a massive catastrophe if they collided with satellites or spacecraft.

“It can’t be overstated how important this is,” says Michelle Hanlon, a space lawyer at the University of Mississippi. “We have these ‘debris bombs’ just waiting to hit.”

Rockets are the biggest piece of space debris

There are now estimated to be orbiting the earth 500,000 pieces of space junk, which are only one centimeter tall. The number of trackable objects larger than ten centimeters is 23,000. These so-called dead rocket stages form an interesting – but also dangerous – category. The 956 known rocket bodies in space account for only four percent of the trackable objects, but make up almost a third of the total mass. The largest empty rocket stages, which were mostly discarded by Russia in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, weigh up to nine tons – as much as an elephant.

These discarded upper stages of rockets that carry satellites or spacecraft into their final orbit are simply left behind after they are released and then orbit our planet. They pose a great risk because they are no longer controlled and could turn unpredictably. If two of them collided, a deadly cloud of “10,000 to 20,000 fragments would be created,” says Darren McKnight, a space debris expert at US debris tracking firm LeoLabs.

Such an event could happen at any moment. “I expect there will be a collision between them at some point,” says Hugh Lewis, a space debris expert at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom. “There’s so much stuff out there.” The result would be a huge problem because parts of the Earth’s orbit would become unusable or, in the worst case, there would be a chain reaction of collisions that could occur Kessler syndrome is known. This could even make human space travel too risky until the debris falls back into the atmosphere after decades to centuries and burns up.

Since the United Nations directive introduced in 2007, which requires objects to be removed from space within 25 years of their operational life, fewer rocket stages will be abandoned in orbit. Most upper stages now retain a small amount of fuel to propel themselves back into the atmosphere after launch. “They now tend to reserve some fuel so they can de-orbit,” says Lewis. But there are still thousands of “legacies” from before this rule was introduced, Lewis adds.

First in sight: Japanese rocket stage

In the rocket stage that JAXA is developing as part of its… CRD2 program (Commercial Removal of Debris Demonstration) is the upper stage of a Japanese H-IIA rocket, which was used to put a climate satellite into orbit in 2009. The three-ton, bus-sized space debris orbits our planet at an altitude of 600 kilometers. If left unattended, Lewis said, it will remain in orbit for decades before being pulled back into the atmosphere by our planet’s atmospheric drag. Then it will burn up and its remains will most likely fall into the ocean.

(Image: Astroscale)

The task of ADRAS-J is to figure out how to get the rocket stage back into the atmosphere more quickly. The probe will approach the rocket and detect it using cameras and sensors examine from a distance of up to one meter. She will check the condition of the rocket, including whether it is intact or whether parts have broken off and are floating nearby. In addition, ADRAS-J will also search for grab points where a future spacecraft could attach. The inspection is expected to be completed in April. It is the first time an abandoned piece of space junk has been examined in this way.

“Developing a service device that handles a three-ton piece of debris presents many challenges,” said Mike Lindsay, Astroscale’s chief technology officer. “The biggest challenge is dealing with the level of uncertainty. The object has been up there for 15 years. It is uncontrolled. We don’t communicate with it. So we don’t know how it moves, what it looks like and how it works has aged.”